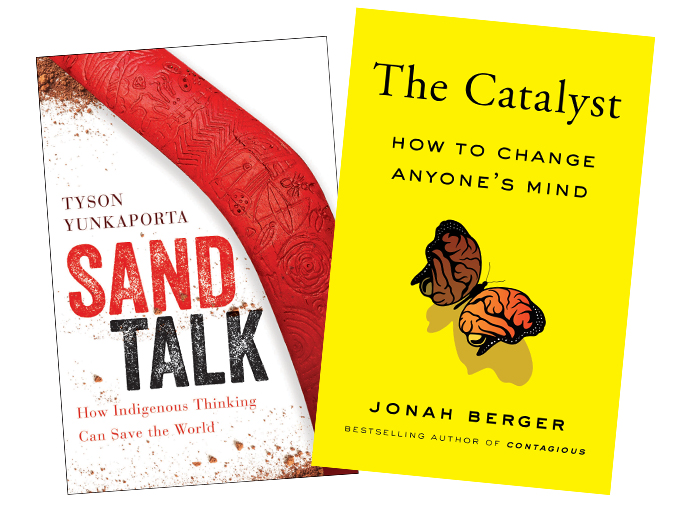

The Catalyst: How to Change Anyone’s Mind by Jonah Berger, Simon & Schuster, 2020

Sand Talk: How Indigenous Thinking Can Save the World by Tyson Yunkaporta, HarperOne 2020

These two new books could hardly be more different on the surface.

The Catalyst: How to Change Anyone’s Mind, by Jonah Berger, is a highly tactical, applied, and extensively footnoted volume by a renowned Wharton marketing professor, business consultant, and internationally bestselling author. Sand Talk: How Indigenous Thinking Can Save the World, by Tyson Yunkaporta, is an interesting, but dense, meandering, highly-abstracted series of anecdotes by an Aboriginal clan member and academic that focuses upon the wisdom of individuals among the indigenous peoples of Australia, as passed on through cultural practices, physical objects, drawn symbols, and oral traditions. What both books share, however, is that each encourages us to get outside of rigid world views and reflexive ways of thinking and to consider alternative points of view so that we can become more effective change agents.

At its core, The Catalyst: How to Change Anyone’s Mind is about strategies to combat the cognitive heuristics and biases that all humans experience. What makes this book fresh and highly applicable is Berger’s assertion that we can be more effective change agents by simply reducing the barriers to transformation. His five transformation categories have the REDUCE mnemonic: Reactance, Endowment, Distance, Uncertainty, and Corroborating Evidence. Each chapter focuses on one of these concepts, exploring it through published literature, stories from Berger’s experience as a practitioner, and a case study. Berger brings it all together in a final case study that demonstrates how all five elements came into play during a persuasive World War II campaign to get civilians to conserve food.

When reporting and creating deliverables, researchers must be catalysts, helping clients commit to making decisions based on the research findings that will help the business succeed. Berger’s model can help with both devising actionable recommendations to get consumers engaged with a product or brand and also shaping how we communicate those recommendations to clients and stakeholders.

Sand Talk: How Indigenous Thinking Can Save the World is focused on solving big issues by injecting indigenous thinking into complex problems of modern society, such as climate change, a point made all the more poignant by the recent devastating fires in his homeland of Australia.

Yunkaporta has an unconventional writing process. He starts to produce each chapter by carving an object, such as a boomerang or bark bowl, based on his conversations with other thinkers—ranging from Aboriginal elders to academics to youth. Only after exploring a concept in this way does he translate his thinking into writing. It would have been helpful to include images of the objects he created in preparing to write.

Living sustainably—at every level from family to community to planet—is a core message, and the interconnectedness of everything is a repeating theme. The Respect, Connect, Reflect, and Direct process toward the end of the book is Yunkaporta’s effort to provide a practical strategy for accessing indigenous knowledge and indigenous methods of being and doing. One can’t help noticing it’s also applicable to interpersonal or client engagements, which are most successful when they start with profound respect and relationship-building, and only then move on to gathering data and measuring, before finally implementing strategies for change. As Yunkaporta aptly points out, when we invert this process, things can go terribly wrong.

Readers be forewarned: this is a challenging book for anyone who is a linear, word-oriented thinker. It is dense and, at times, difficult to follow. There are no chapter numbers, no index, nor a table of contents. However, as the book progresses, and particularly when Yunkaporta brings it all together in the final chapters, especially “Lemonade for Headaches,” it is intensely satisfying and resonant.

Perhaps the best testament to Yunkaporta’s central message about indigenous thinking, with its reliance on physical objects, stories, and symbols, is that I came to rely upon his symbols as an essential road map to his arguments and ideas. Eventually, I found myself skipping to that part of each chapter, so I could get a handle on what he was trying to say. In a crazy way, the process of reading the book forced me to become a little bit of an indigenous thinker, which is very meta, and, if it was truly the author’s intent, brilliant.

Be the first to comment