Joseph Coughlin is the founder and director of the AgeLab at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Joe and his team study the impact of global demographic change and technology trends on consumer behavior, business innovation and public policy. The Wall Street Journal named Joe one of “12 pioneers inventing the future of retirement.”

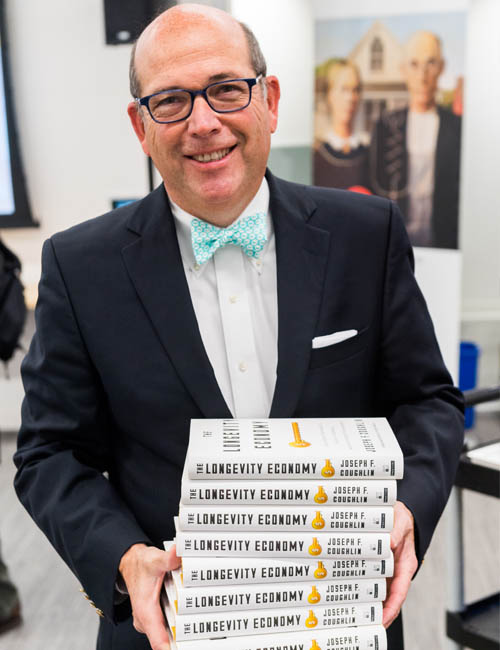

I talked with Joe recently about the AgeLab and about his new book, The Longevity Economy: Unlocking the World’s Fastest-Growing, Most Misunderstood Market, where he describes how businesses can create a new narrative for old age.

Kay: Let’s get started by talking a little bit about what the AgeLab is and its mission.

Kay: Let’s get started by talking a little bit about what the AgeLab is and its mission.

Joe: The AgeLab is a multidisciplinary program at MIT that’s based in the School of Engineering but draws from the Schools of Architecture and Planning to really understand how we can invent Life Tomorrow and to solve what I call the longevity paradox. And the paradox is this: perhaps the greatest success of humankind is living longer, but now the challenge is what do we do with the time that we have and the time that we continue to gain. The AgeLab is trying to develop new ideas, new products, new services, new approaches to understanding and developing Life Tomorrow.

Kay: What kinds of products and services have you created so far?

Joe: We started with the auto industry to learn how can we use new technologies in the car, in transit and other things to enable people to stay mobile, safe, and seamlessly secure throughout their lifespan. As we move to the autonomous car, we have started to redesign the interfaces of the cars that are out today so that people can learn, use, and eventually trust and adopt new technologies that will be used by 20-year-olds and by 80+ year-olds as well.

We’ve worked with the insurance industry to come up with new product riders to improve homeowner insurance to keep older people safe and secure, and making it possible for them to age in place. We’ve worked with retailers to rethink the design and the layout of their stores, not just to be age friendly but also to make it a better consumer experience. Because if I make it better for an older adult, removing that friction and frustration and that fatigue that older adults are not particularly fond of, guess what, I’ve made it more attractive for every consumer out there.

So, our work is across transportation and retail and housing and health, and we’re having great fun with a great team.

Kay: How do you do qualitative research at the AgeLab?

Joe: One of the fun things about a multidisciplinary team is you have many different disciplines, like engineering and planners, gerontologists and social workers looking at the same problem. If you ask them what the problem is, they will all use a different language. That richness—and shall we say creative conflict—between the disciplines in the lab gives us the ability to develop new insights and new language, to come up with very creative and innovative ways to rethink a product, to rethink an experience and the like.

There is a growing divide out there between quantitative research and qualitative research. Every sentence these days has to be ended with the phrase “big data.” My challenge to big data advocates is the following: Data, data everywhere, and not a drop of knowledge. We use qualitative research to bring insight to big data. We are the third-largest data storer on campus at MIT, and that says something, so it’s not that I’m discounting big data. But now the divide between quantitative and qualitative needs to be bridged. It’s often qualitative insight that makes the difference between understanding what’s simply a correlation and what’s a causation.

Kay: So you facilitate many different professional perspectives and blend them with insight from real users.

Joe: Today about 70 feet down the hall from where I stand are our lifestyle leaders, our 85+ panel is here. There’s close to 30 people over age 85 that are more affluent, highly educated, a highly biased sample of 85- to 99-year-olds. One of our gentlemen turns 99 this month. If a product or service does not work for them, it’s probably not going to work for anyone. The way that we harmonize these very different approaches, the different languages and different methods, is by the one thing we have in common—it’s the user.

It’s not just about responding to the consumer; it’s about understanding their needs, their wants. Transcendent design, unlike universal design or design thinking (which we used to just call thinking) is about how we excite and delight. How do we come up with new ways of doing things that the consumer didn’t even know that they wanted until you do it for them? Real innovation, real quality engineering, real experience is about surpassing what they thought they needed to give them something that they now want more than anything else.

Kay: It’s a transcendent leap of imagination!

Joe: I think it’s a bit of imagination, but it’s also drawing upon the real skills of qualitative insight, trying to understand where the emotion is, what is the basis of what people or a user or a caregiver is doing. If it’s communication, how do we make the communication richer? How do we make it better? How do we make the conversation in that connection be more than pill reminder systems and “Help, I’ve fallen and I can’t get up”? The basis is basic human behavior. It’s communication.

But we try to jump at the next step, which says, okay, if I am going to develop a pill reminder system, let’s dovetail it with something that we know that people really want, not just the adult daughter or a grandchild calling grandma saying, “hey, did you take your meds?” but actually giving an opportunity for the grandchild to say, “hey, grandma, I had soccer practice today,” and, oh by the way, the system is also going to say, “did you take your meds?” So, not being so profoundly rational that we leave the consumer’s emotions behind.

Kay: In your book The Longevity Economy, you say businesses that create products for older people should study “the Lead User”. Who is the Lead User?

Joe: This is where your listeners and readers who are men can go out and make a sandwich or maybe a good strong drink. As we see it here in the lab, the Lead User, and the real innovator in the new longevity economy, is a woman. More likely than not it’s a 47 to 57+ female. She understands the jobs of longevity long before most men do. She’s not just a mother, she’s also a caregiver, she’s also working. She’s the chief financial officer and chief purchasing officer of the house.

It’s not biology that makes women that lead adopter and lead user in the longevity economy, it’s the role. Whether they work or are a mother or the like, they are doing all the things and providing the supports, the information seeking, the research online, advising and specifying the medications, the money, the home improvement, not just for their house, and increasingly as they age, not just for the Millennial family house, but also she probably has more parents and in-laws than she ever planned on in addition to having children. And as a result, she tends to be the lead adopter.

So, we track middle age and older women more than almost anyone else because they are the systems integrator and the innovator for the longevity economy. High touch is the number one competitor and the number one requirements definition we need for high tech.

Kay: How do you find your study participants?

Joe: We are very fortunate that the lab has one of the largest databases of people that we can bring in, upwards of 10,000 just in the region. We recruit them through ads in the paper and TV, depending on the experimental work, in specialized areas such as the Registry of Motor Vehicles or hospitals. Last year we ran upwards of 2,000 subjects through the lab and probably touched about another 25,000 people in five different countries around the world on everything from focus groups to surveys to deploying equipment to somewhere between cool and creepy, putting GPS on people and tracking entire households in India to understand not just mobility patterns but activity patterns.

Kay: Are there industries that you think are doing a particularly good job of developing products for older people?

Joe: The companies that do best are those that try to understand their consumer and often did not even know that they were designing for an older adult. The products that are designed for older adults are clunky, blue, beige, and have got numbers the size of my hand. As we like to say for the auto industry you can’t build an old man’s car, because a young man, and a young woman, won’t buy it. But here’s the punchline. An old man and an older woman will run far, further, and faster from it than even the younger cohort will.

(For example), Dyson is an incredible product. Not only is it usable, not only does it do the job, but it’s also very light. It’s easy to understand. It comes in bright colors. It does not say old man or old woman’s vacuum. We’re seeing little spots of innovation though not necessarily where you would expect them. The home-equity-loan-priced hairdryer that they make, for instance, is exceedingly light for that older woman who wants to dry her hair and be able to get her arm around the back of her head and up and around up high. So, that’s a great example.

In terms of designing of spaces, I think that the work that we did with CVS is inspiring. No one knows that that store was made for an aging population, the aisles were wider and the shelves were lower and the signage was made high contrast, and now there’s a place to put a purse at the cash register. And guess what, the mother with a child or the gentleman going through wanting to find something quickly now appreciates it because it was made age ready and so, therefore, it made it easier for all.

Kay: I have one last question, and it’s back to something you said in your book about how the sharing economy is being embraced by older people. Would you talk a little bit about that please?

Joe: While the sharing economy—the Ubers, Blue Aprons, and essentially life on demand—appears to be designed and developed by the young Millennials, the older Boomers and the Silent Generation like it too because it provides easiness of use. It provides convenience. It’s on demand. It’s to the door.

What we have found in the lab, and we did a regional experiment here in the Boston area, finding that it may be cheaper for you to stay in your home aging in place using the vast variety of services that you could have brought to the door than going into assisted living or many of the aging services facilities and residences that are out there. What we’re really excited about is that the convergence of the Internet of things and the sharing economy is transforming the home as a place into a platform for services that will make it connected and convenient for the young, but also provide care both for the caregiver and the care recipient.

Kay: All of this innovation is being driven by older people because we are now such a large part of the economy.

Joe: Yeah. As I write in the book The Longevity Economy, it’s the new old age. [Those who are] 60+ alone are the third largest gross domestic product in the world. So, United States, China, and the 60+, and here in the United States the 50+ make up 70% of the buying power. This is not your grandfather’s old age.

Kay: Great. Thank you so much.

Joe: Thank you. Take care now.

Be the first to comment