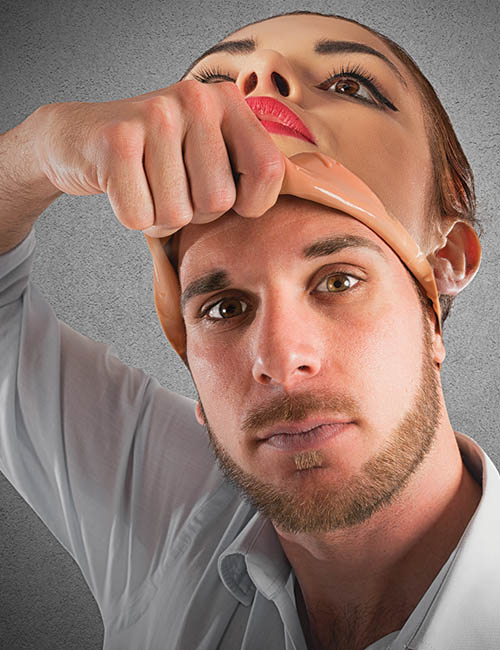

Rumors hinted at it. Der Spiegel Online confirmed it. A whistle blower tipped off Der Spiegel Online, one of the most widely read German-language news websites, about large-scale cheating among data collectors in Europe. In one case, of 10,000 completed records in a data set, over 8,000 were falsified by the field service. Imagine the impact on companies that needed these research results to make decisions. This might include those that manufacture medical devices, over-the-counter medicines and prescription pharmaceuticals.

Not surprisingly, this raises concerns among both clients and researchers. Corporate decision makers rightly questioned whether they were receiving accurate information from their field services. Researchers faced the same dilemma.

This article highlights some of the methods used by qualitative research experts around the world to omit cheaters and repeaters and to ultimately recruit true blue participants. In sharing these best practices, this article hopes to:

- Encourage conversation about best recruiting practices,

- Foster thought about creative approaches to recruiting, and

- Promote the highest industry standards.

Database Diligence

Database Diligence

In several countries like Brazil, Canada, Mexico, and the Czech Republic, national participant databases help confirm a person’s demographics as well as whether or not an individual’s past participation includes any incidence of cheating. In the US, our independent recruiting partners keep track of participants and omit reported cheaters from their database. Additionally, they track the frequency of participation and use this information to curb repeat participation. Of course, these national associations and independent recruiters’ efforts are not foolproof because the process depends on self-reporting.

Using Pre-Work to Confirm Appropriateness for a Study

In countries where smartphone technology is widely used and relatively affordable, prospective participants are routinely asked during the recruiting process to send a photo. Photo evidence literally becomes part of the screening process. This request might be for a picture of a specific product in the place where it is kept in the home.

Posed pictures of a new product displayed on a table raise questions about whether or not the person really uses the product and alerts moderators to instruct recruiters to ask additional follow-up questions or to simply omit this prospective participant. Pictures of a half-used tube of toothpaste tucked away in a bathroom vanity drawer more likely indicate actual use. Not only does this approach serve to confirm category and/or brand use, it also can yield wonderful insights into product usage. For example, who knew that floss pick users stored these products in the console or door pocket of their cars? This single example of incorporating photo evidence of product use into the recruiting process, confirmed later during focus groups, opened the client’s eyes to an unknown aspect of the product among users.

Pictures also can show whether or not someone really holds a membership or subscription. Say you need Netflix subscribers or those served by a certain utility company. We ask reported Netflix users to show their subscription information or request individuals who say they use a certain utility company to send a copy of their bill that includes their name. This even works with confirming ownership of high-end products. For example, we might confirm that someone really drives a Lexus or wears a particular type of jewelry by requesting they send photos of themselves with the product. And, we’ll be very specific, instructing potential participants to show themselves inside the car or wearing the jewelry so that we can see their face. Absolutely foolproof? No. Effective? Yes.

Rescreening

Across the globe, it is common practice to rescreen participants at the research facility before they come into the focus group room using a simple pen and paper screener. Moderators then review these screeners before taking qualified participants into the room, leaving unqualified participants in the waiting area.

Even with rescreening in the holding room, an inappropriate participant can get into the focus group room. So more experienced qualitative researchers routinely include questions at the very beginning of focus groups that help determine the suitability of each participant. For example, the moderator might say, “Tell us your name and one thing that you really count on product X providing.” By listening carefully to these early responses, researchers can determine if someone is inappropriate for the research or not. Some of us refer to this as our sixth sense. We quickly ferret out the truth using seemingly innocuous questions.

We also routinely have our recruiters’ supervisors rescreen participants. And in several instances, we have an internal person who rescreens, or as it’s referred to locally in India, “back-checks” every participant. Back-checking might even involve going to participants’ homes to ensure their appropriateness. A similar approach is used in parts of Latin America.

More about Verifying Identity

In face-to-face research, we might ask to see a participant’s identification as they sign in. This might be a driver’s license or some other form of photo identification. This keeps the neighbor down the street from sitting in for a properly recruited participant. Though perhaps hard to believe, this has happened to me.

For both face-to-face and online work, we use various methods to ensure participants are who they say they are. We might double check a recruit via Facetime or Skype so that we can see participants and verify their surroundings. Is their office really in their home? Do they really have a dog?

Also, we might recruit through social media, targeting groups that we know have a high likelihood of fitting the participant profile our clients require. Perhaps we need to find men who have prostate cancer—there are a number of sites on Facebook where we are likely to find these gentlemen. Similarly, we might go to groups on Facebook to find those who care for a parent with Alzheimer’s. We are transparent in our offer to give voice to these individuals and know from experience this approach helps us to find the right participants.

And, we might physically go to where the appropriate participant is. For example, we might go to the beach to find people who are using a specific kind of sunscreen or wearing a certain kind of flip-flop. Then, there is no doubt; we see them using the product.

Open-End Validation

Interestingly, one of the articles written after the Spiegel exposé called out open-ended queries as a way to help determine whether or not a survey respondent is real. Reviewing what people write in their text-box responses gives researchers a window into the authenticity of individual respondents. For example, does the response make sense in terms of the question? Is the text-box response consistent with the other check-box responses?

Qualitative researchers spend our professional lives asking open-ended questions, so it may come as no surprise that we have developed specific processes for excluding inappropriate participants and to minimize cheating.

Countering the Low-Price Pressure Blamed for Cheating

Particularly in Europe, companies have started asking those researchers who

submitted the best proposals to come back with their best price. Companies are effectively asking top-quality researchers to submit a lower bid on their work so that the corporate entity can choose among the most qualified companies and get a really low price. It is this lowest-price pressure that some in the industry say is the reason field services in Germany cheated.

Doing work well requires a certain budget. There is an old adage in India, “if you pay peanuts, you get monkeys.” Rather than skimp on quality, it may be better to pass on a bid and say, “No, thank you.”

In competitive bid situations, experienced qualitative researchers put forth their best ideas and their best prices. After all, we want the work or we would not invest time and resources into the competitive bidding process. So, there are times when we have to respectfully decline to compete if we are asked to jeopardize the quality of our work and arguably damage the industry.

Acknowledgements:

A special thanks to Think Global colleagues for their input.

Be the first to comment