Technology has changed and expanded the ways we communicate. From snail mail to social media, today we can choose which senses to tap and how we want to exchange our thoughts and feelings. Online or offline, human communication adapts to the perceived needs of the situation.

Some of the most significant differences between online and in-person communication are the potential for anonymity and the depth and duration of feedback.

When we are face-to-face with someone, we are exposed and accountable. Our expressed opinions and reactions are affected when we look another in the eye. While in-person engagements include helpful visual expressions

for the recipient like facial expressions and body language, online communication can free respondents from the tacit assumptions and gazes of others, encouraging candor and freedom of expression.

This online freedom of expression can be both a blessing and a curse. While the arts of bullying and self-promotion are rampant across social media, self-expression in a controlled research setting is markedly different.

Let’s take a look at how online communication compares to face-to-face and how to determine which online research method works well given different objectives.

Custom Designing Studies

Custom Designing Studies

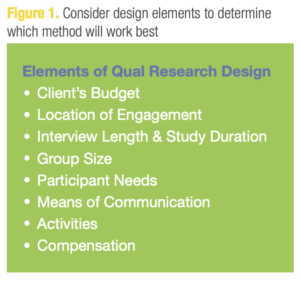

What once were two distinct qualitative research disciplines—online and in-person—are now two factors of many to consider when designing a research project. Objective, budget, location, interview length, study duration, group size, participant qualifications, means of communication, activities, and compensation all come together in the design.

Custom-designing studies may sound daunting, but the strategy is fairly straightforward: know where you’re going and your options for getting there. In other words, understand which research designs will best achieve your objective within budget.

Choosing the Right Method

Choosing the Right Method

To determine which research method will work best, work backward from your research objective and consider the elements of design (see Figure 1).

For a qualitative researcher, the study objective is always due north. With a keen eye on the final destination, and ideally some understanding of the client’s budget, we can determine what is needed and plan the most appropriate path forward.

Considering where you are going before you pack is an approach that is neither new nor revolutionary. Also known as “backward planning” among educators, “begin with the end in mind” is second on Stephen Covey’s popular list of “Seven Habits.”

Meeting your client’s research objective is the goal—the big question your client needs answered so she can move forward. We start building our research design from here, because it is the only piece of the puzzle we usually have at this point.

Additionally, knowing what decisions your client will be making from the research results is a nice bit of information to have, especially early in the design development. When the project is over for you, the business mission continues for your client. Bridge the gap from research findings to actionable insights, and you’re crossing the finish line a winner.

Engage to Deliver

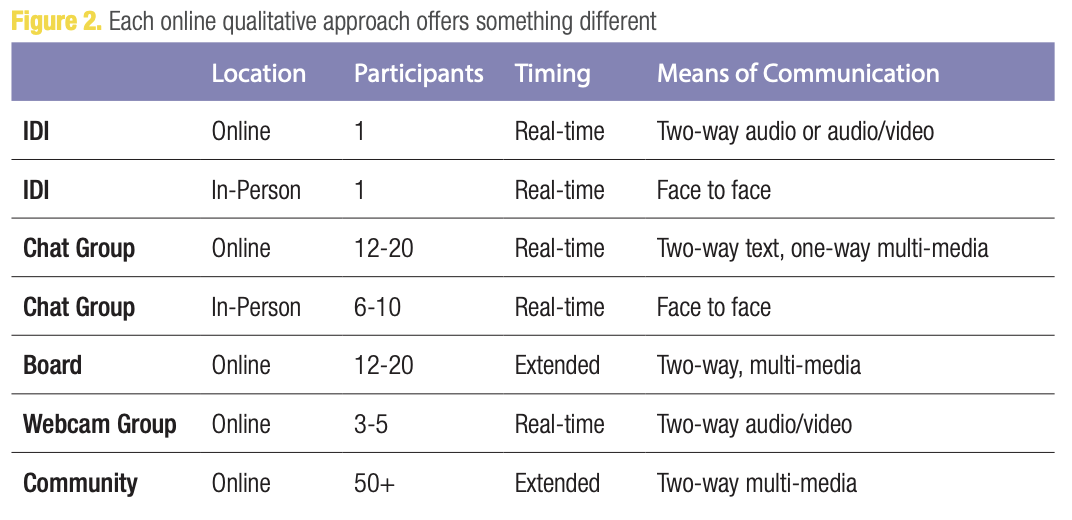

The research objective and the client’s budget help determine the best means of engagement. Each of five basic online qualitative approaches offers something different (see Figure 2).

- Online offers anonymity, prompting freedom of expression without the risk of others’ judgmental gazes. Sensitive topics or shy respondents benefit from anonymous settings like bulletin boards and chat groups.

- In-person allows for facial expressions, body language, and tone of voice, offering the researcher multiple factors from which to gauge response.

- Real-time offers immediacy, giving the researcher instant feedback for analysis.

- Extended time studies allow for tracking thoughts and behaviors over multiple days.

- Groups offer a dynamic exchange of communication and reactions to ideas and expressions of others, while one-on-ones are more intimate.

- Text-only conversations allow for anonymous freedom of expression. Visibly fleeting communications, as in scrolling text in an online focus group, also can bolster feedback, as deep or divisive discussions are most effective when the communication lacks permanence and is not continually visible to participants.

- Audio allows participants to be heard, while audio/video adds a face, and thus some non-verbal communication, to the voice. Multi-media capabilities offer engagement choices.

Tools are the last piece of the research design puzzle. The increase in tech devices has led to an influx of tech applications, so if you are looking for a particular engagement in a particular format with a particular deliverable, you’ll have no trouble finding several options. From paid to free, supported to risky, useful to useless, there’s a feedback app for that. Try a quick search or QRCA members can post online at the QRCA Member Forum for some honest user feedback.

Tools are the last piece of the research design puzzle. The increase in tech devices has led to an influx of tech applications, so if you are looking for a particular engagement in a particular format with a particular deliverable, you’ll have no trouble finding several options. From paid to free, supported to risky, useful to useless, there’s a feedback app for that. Try a quick search or QRCA members can post online at the QRCA Member Forum for some honest user feedback.

Look for tool features that will allow you to engage with your participants in the desired format. For example, if your client wants to receive long-form video testimonials from participants, you’ll want a tool that can at least accommodate large video files and ideally includes an editing tool or services.

Example 1: Product Usability

A small but mighty technology company has developed new software to manage physical inventory across multiple warehouse locations. The developers have tested it internally to work out the bugs and now want feedback from real customers in different industries across the country. Insights collected will determine the final design before launching the product.

With product usability as the research objective, timing of the essence, and potential respondents all over the map, the project needs a research method that allows for observation of the experience, data collection in real and extended time, and geographic dispersion of participants. And, since each user will be using the software for several months within their own industry, we can assume they will be on different schedules and have unique experiences.

The ideal solution in this scenario is virtual, one-on-one, with two-way audio/video communication: online IDI with screenshare. To accomplish this, tools like WebEx, Join.me, GoToMeeting, and Zoom work well. Choose the one that best fits your deliverable needs (e.g., written report, video testimonials).

Example 2: New Concept Development

A New Jersey landscaping company wants to expand its services. The company currently operates in the northeast region of the state and believes its best strategy for growth is to offer more services to existing clients, as opposed to obtaining new customers by broadening the coverage area. Ultimately, the company seeks to increase sales.

The stated research objective is to identify which potential home services are of greatest interest to current customers. Because potential respondents all live within a half hour of the region center, an in-person engagement, in real-time, sounds logical. Since group discussions (vs. one on one) foster a more dynamic exchange of ideas, in-person focus groups are an obvious choice.

To identify the best qualitative research method in this situation, however, consider other study elements, like budget, privacy, final deliverable, and compensation.

If your client doesn’t have enough money for in-person groups, online chats are a comparable option. Online focus groups can lower project costs by reducing the total number of groups conducted, eliminating the added cost of transcripts, and reducing the total labor hours expended. By accommodating more participants (all geographically dispersed), eliminating moderator travel, and producing instant transcripts, online focus groups can collect more feedback in less time. In addition, respondents could be more forthcoming with their opinions if they are not surrounded by the watchful eyes of neighbors, so a virtual option could have methodological advantages as well.

Go deeper by asking customers to submit videos or pictures of desired home services. Engage participants in an asynchronous, multi-media bulletin board environment, or consider adding projective exercises or homework activities to an in-person group for richer insight.

In Summary

The path from research objective to best methodology may not be straight, but we can cross the finish line a winner with our client by consistently referencing the end goal in the design process, identifying what’s needed to deliver it, and considering the factors that could affect it.

Be the first to comment