By Kendall Nash

Senior Vice President

Burke

Cincinnati, Ohio

kendall.nash@burke.com

Kintsugi

(Japanese: 金継潟, “golden joinery” or kintsukuroi, “golden repair”)

My first encounter with the art form of kintsugi was love at first sight. There was something about its vulnerability on display that moved me: that what was once broken has now been made more beautiful, even more meaningful—and in many cases more valuable—than in its pristine, original state.

I was sitting in a large auditorium at a local event taking in a quick-scrolling reel of images on the large screen overhead. As the speaker shared the history and richness of kintsugi, I was totally enthralled.

A kintsugi artist takes a broken piece of pottery and rejoins the pieces together with a mixture of lacquer and gold, silver, or platinum dust. The individual making these repairs is certainly more than a skilled craftsperson, as the works of art elicit emotions and convey ideas. Holding a beautiful plate or bowl in my hands that has been repaired through the art of kintsugi makes me feel something.

Though its exact origins are unknown, kintsugi rose in popularity in Japan in the late 16th century. Ribbons of gold spanning different sizes and directions across each piece result in striking and unique pieces of pottery. But its true beauty lies in the way it embraces imperfection—a particularly progressive notion during a period when imperfection was far from celebrated. A more “sensible” artisan might repair pottery with every effort to blend it together in a way that the naked eye wouldn’t realize it had ever been broken. Kintsugi turns that notion on its head. In the spirit of the Japanese wabi-sabi philosophy of honoring the imperfect, using golden joinery to repair these pieces signals that not only are the breaks “okay,” but the break and its repair are the source of its beauty.

My introduction to kintsugi was in the context of how we as people are broken, messy, and perpetually imperfect—but all that brokenness still on display as part of our authentic story is what makes us beautiful and priceless. Not only being okay with our seeming imperfections but celebrating them! As someone in the business of studying other humans, that was a rallying cry I could get behind.

KINTSUGI AND THE ART OF RESEARCH

For several days, I found myself coming back to the images I had seen of these gold-ribboned pottery pieces. The researcher in me couldn’t help but draw parallels to the work that we do. Our industry has long urged us to push beyond “the what” to explore its richer underpinnings, mining for insights that extend further beyond observation alone. While we all may support this concept in theory, the most tempting place for a classically trained researcher to live and stew is in the comfort of the almighty observation: the evidence right before us that can be taken at face value, free of its perceived riskier interpretation and implication. Delivering this observation-based, unquestioned evidence to clients is like offering a traditional pristine piece of pottery. It’s safe and acceptable but lacks the dimension and emotive abilities of a kintsugi piece.

Often, in this industry, a line is drawn between thinking like a researcher (focusing on the evidence before us) and thinking like a strategist (oriented toward what we’ll do with the learnings). Though our intentions are good, this separation between these facets of our thinking may be limiting the ways we’re able to support our clients’ ability to impact their business.

Over the years, the brand teams I have done the most significant good for—that is, helped provide the most meaningful, strategic direction that has made a real business impact—are not those I have delivered only pristine, impenetrable evidence-based observations. They are the instances where I rolled around in the mess, played with ideas, threw notes up on the wall, and have tugged on threads to see where it leads to something more or where it simply unravels. It’s not the pristine, original state observations that move organizations; clients are moved by the impactful insights that come from breaking it all down and joining it back together through the meaningful connections we unlock.

Years ago, a client of mine nudged me even further on this journey. With her encouragement, every slide in the decks we delivered together was centered around the connected story. Observations from our research simply served to support it. As the learning was socialized, I noticed that this approach more effectively drove teams toward action. Much like a potter must keep clay centered on their wheel for it to form, the connected narrative must remain our focal point.

As easy as that is to say, it turns out that it can be quite uncomfortable to do. As researchers, we see ourselves as the voice and conduit for the customer, thus often feeling a sense of duty to ensure the observations are fully showcased. What we fail to see is that in leading with the observations (e.g., “we learned this and this and this”), we’re diminishing their power. Brand teams take greater action when we—as researchers—lead with the connected story and leverage the data observations as supporting actors.

BREAK INSIGHTS AND REBUILD THEM

BREAK INSIGHTS AND REBUILD THEM

To more deeply immerse myself in kintsugi, I gathered with friends to try our hand at this art form. We didn’t have any existing pottery in need of repair, so we purchased beautiful, brown ceramic bowls. They were the perfect shape, had a smooth lip, and felt nice in our hands. We found ourselves squeezing our eyes tightly closed as we bagged them and swung the small hammer. We had learned that it took only a couple of strategic hits with a moderate amount of force to create the cracks we sought to rejoin. Just as it’s difficult to leave content on the cutting room floor, it can also initially feel painful to take a mallet to these gorgeous insights we’ve so meticulously served up to break and rebuild them into a connected story. Just as fine artists take intentional steps to develop their own skills and refine their craft, we can do the same to develop a more strategic mindset. Streamlined frameworks like “What > So What > Now What” are a great starting place to begin naturally thinking about how the business should act upon any particular insight, but there are exercises we can put into practice to help reframe our thinking.

CAN WE LEARN TO THINK MORE DEEPLY?

Posing this question some time ago, I came across Harvard’s Project Zero. The project was founded primarily to deepen student thinking. Of course, the beauty is that we’re all students of something. The organization has collated and continues developing what they call “thinking routines”—essentially sets of questions or mental models to work through to support student thinking. Upon first learning about thinking routines, I appreciated the sentiment that the word “routine” suggested (a sequence of actions regularly taken). It means “thinking” doesn’t need to be quite so unstructured, as many have come to believe. It means there are steps we can take to become deeper thinkers. Having steps to follow means it’s something anyone can replicate to develop their own strategic skills.

primarily to deepen student thinking. Of course, the beauty is that we’re all students of something. The organization has collated and continues developing what they call “thinking routines”—essentially sets of questions or mental models to work through to support student thinking. Upon first learning about thinking routines, I appreciated the sentiment that the word “routine” suggested (a sequence of actions regularly taken). It means “thinking” doesn’t need to be quite so unstructured, as many have come to believe. It means there are steps we can take to become deeper thinkers. Having steps to follow means it’s something anyone can replicate to develop their own strategic skills.

With swaths of qualitative and quantitative data before me, I often need to leverage different vantage points to find the most robust insight opportunities. I put a lot of tools to use, but three that I’m particularly keen on because of their simplicity and wide applicability are:

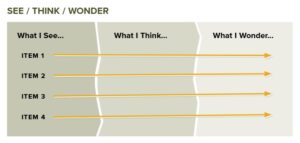

- SEE / THINK / WONDER

- THE STRATEGIC NARRATIVE

- THE FEYNMAN TECHNIQUE

THREE KINTSUGI MINDSET TOOLS FOR CRAFTING INSIGHTS

- See / Think / Wonder

First introduced to me by an educator, this framework is often used with students to help them learn to look deeper into any given topic. This is likely the simplest tool in my kit, yet highly effective at getting my brain over the initial hurdle by immediately triggering curiosity and getting me in a position of questioning the data I’m seeing. After narrowing down to a handful of key observations, I simply write them down in the first column. I don’t assess which are most meaningful or pressure myself to immediately interpret them.

After I have them all written down and have sharpened each a bit, I then move to the next two columns. I take each observation in isolation (i.e., what “I see”) and reflect on what “I think” (e.g., “What else is going on here?” or “What do I see that makes me say that?”), and what “I wonder” (e.g., “What new questions does this spur for me?” or “What questions do I still have?”) in order to begin identifying new territories to explore in the data. It’s like picking up a beautiful piece of art in my hand and spinning it around to inspect it from different angles. It slows me down with a purposeful set of steps to put my mind in a more inquisitive posture.

For example, we spoke with decision-makers responsible for selecting new CRM software for their enterprise.

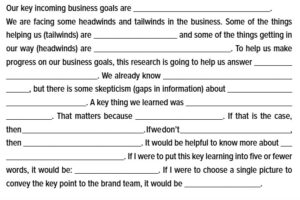

- The Strategic Narrative

This mental model is helpful because you (and anyone workshopping it with you) forget it’s even a model. Think Mad Libs. Much like fill-in-the-blank exercises, we might take participants through a qualitative interview; this approach causes us to step out of the rigidity that often accompanies analysis mode. Some of the items in the narrative are tactical, and others more projective. It’s the combination of the two that makes this exercise a useful one for breaking down insights and looking instead for points of connectivity.

This mental model is helpful because you (and anyone workshopping it with you) forget it’s even a model. Think Mad Libs. Much like fill-in-the-blank exercises, we might take participants through a qualitative interview; this approach causes us to step out of the rigidity that often accompanies analysis mode. Some of the items in the narrative are tactical, and others more projective. It’s the combination of the two that makes this exercise a useful one for breaking down insights and looking instead for points of connectivity.

We’ll run any given observation through the paces by building out its “story” to see where there may be something richer to uncover beyond the surface. Begin by looking at the business goals and relevant KPIs this observation connects to, and then work through a series of prompts. The prompts include assessing factors that could spark support or skepticism, considering how the insight fits into the broader ecosystem of existing knowledge in the business, and asking what additional primary or secondary research would be enlightening if it were to exist. Importantly, share these prompts with the full team before interviewing begins so that the team might have this lens in mind while listening.

Final prompts force the researcher to boil it all down. For example, what is the ONE BIG IDEA that the data points to? My favorite projective for final prompts: “If you could use only one picture to make the point to a brand team about the insight, what would it be?”

For example . . .

This systematic approach of working through a set of questions causes the researcher to break the insight into pieces and see how it might rebuild into a more strategic narrative from which the brand team can be compelled to move.

- The Feynman Technique

Celebrated as a four-step learning method, the spirit behind Richard Feynman’s technique does wonders for forcing researchers to clarify, simplify, and then optimize insights.

Celebrated as a four-step learning method, the spirit behind Richard Feynman’s technique does wonders for forcing researchers to clarify, simplify, and then optimize insights.

The approach is simple. Take a complex concept and simplify it as if you were explaining it to a child. To do so requires that we get to the crux of what we have learned rather than hiding behind complex data visuals or fluffy language. By forcing ourselves to use clear and concise words to explain the observation, individual pieces of the narrative puzzle become more evident—making it possible for us to then focus on their interconnectivity.

Applying this technique to the process of distilling insights, we must (1) first clarify the observation. We then (2) explain it as we would to a child in simple language. In trying to do this second step, we almost always (3) identify gaps in our knowledge or a recognition that some aspect of what we are trying to convey is difficult to do simply. That helps direct us to other places we need to examine further. Building upon what we initially observed, we can now (4) simplify our explanations. Taking this further, we’ve added a fifth step of posing the question, “Why does this matter?” to continuously anchor in the business strategy and ensure the insights are in service to the bigger, connected story.

Of course, these are only three of countless exercises or frameworks you might deploy. Try different things, shake it up, and get out of your own way of thinking for a while. When you have an opportunity to work on some of these frameworks with other teammates, take the time to do it. The discussions become more powerful. You’ll begin to connect dots that otherwise may not come to light when limited to one individual’s perspective.

Roll your sleeves up and break the insights to create a more powerful story

It feels risky to make bold statements. It’s a lot easier to deliver observations. But brands need researchers to get out our mallet and break it, play with it, add another layer in, and then find the golden connections that aren’t immediately apparent. That’s what the most valuable research delivers. It’s messy, but it’s fun. It generates energy and nudges us into more strategic territory.

It feels risky to make bold statements. It’s a lot easier to deliver observations. But brands need researchers to get out our mallet and break it, play with it, add another layer in, and then find the golden connections that aren’t immediately apparent. That’s what the most valuable research delivers. It’s messy, but it’s fun. It generates energy and nudges us into more strategic territory.

A golden repaired bowl is infinitely more interesting and powerful than its original state. So, get a little uncomfortable and smash the notion of pristine, perfectly packaged observations. Kintsugi reminds us that the golden joints—connected insights—are what make the masterpiece.