By Jani de Kock, Founder, First Person Research, Copperleaf, South Africa, jani@firstperson.co.za

By Jani de Kock, Founder, First Person Research, Copperleaf, South Africa, jani@firstperson.co.za

Imagine unlocking the power to unravel complex challenges, ignite innovation, and craft solutions that truly resonate with people. In this article, we’ll explore design thinking (DT) by delving into its process, tools, and mindset. Through the lens of a real-world scenario, we will look at how DT can reshape the landscape of problem-solving and qualitative research.

What Is Design Thinking?

DT is a human-centered approach to problem-solving that holds tremendous potential to enrich the work of a qualitative research practitioner. The best definition of DT that I have found is:

“Design thinking is the discipline of finding human problems worth solving and then creating viable new offerings in response to those problems. It is a process, a set of tools, and a mindset.” —Dr. Dawan Stanford, president, Fluid Hive, and interim director of Design and Innovation at The Ohio State University

Which Problems Can Design Thinking Solve?

DT is not suitable for all problems. Some problems (e.g., some accounting or engineering problems) can be solved purely with technical knowledge. DT is most suited for problems that involve humans. It is particularly relevant to complex problems that have multiple variables, multiple stakeholders, and no clear path to one solution; some people call these “wicked problems,” a term coined by Horst Rittel. Take, for example, How might we help kids make friends in a new school? How might we increase vaccine uptake in sub-Saharan Africa?

DT produces human-centered, impactful interventions, and it comes with a compelling story that will help decision-makers understand and empathize with your target demographic, ultimately driving their engagement and support.

Let’s consider DT with these three lenses:

- DT as a process

- DT as a set of tools

- DT as a mindset

Design Thinking as a Process

A process is a series of consecutive steps toward an end goal.

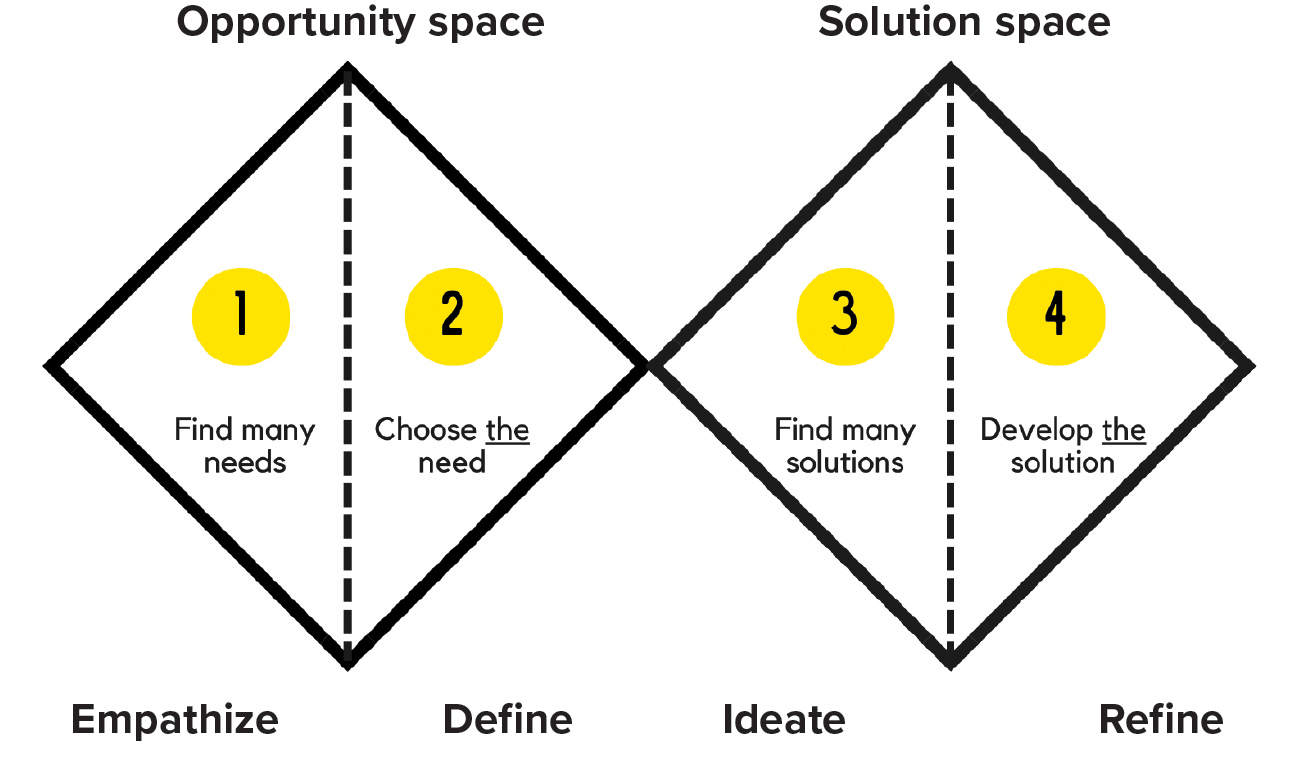

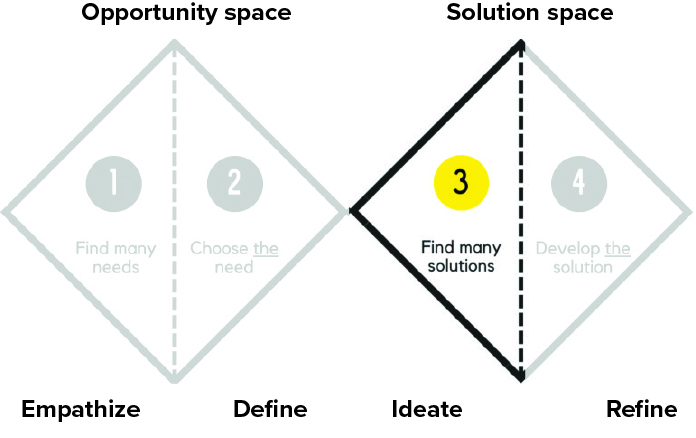

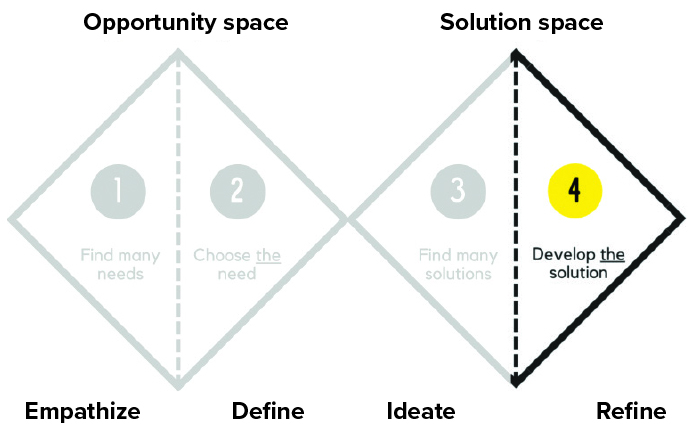

The double-diamond shape below depicts a four-step DT process.

- In Step 1, we empathize with the people we are trying to help and identify all their needs.

- In Step 2, we select the most important need to address.

- In Step 3, we ideate and come up with many possible solutions.

- In Step 4, we choose a solution, prototype it, test it, and refine it.

A Worked Example of a Design Thinking Project

Imagine receiving a brief from a city like Johannesburg, South Africa. The city would like you to run a co-creation study. Visitors to public libraries have been steadily declining over the last decades. The city also has many micro-entrepreneurs in low-income areas; small businesses like hairdressers, shops selling fruit and snacks, clothing shops, and tailors run out of homes or on the streets in local communities. The city council wonders if the libraries can be repurposed to help the entrepreneurs. You decide to investigate with a DT approach.

My first instinct would be to get excited about using the libraries as business hubs. This, however, is not the DT way. The DT way is to set the idea of repurposing the libraries aside for the moment. If the city is serious about helping entrepreneurs, then we need to start with them!

Step 1: Empathize—Your work will entail in-depth qualitative research to understand the network of the city’s micro-entrepreneurs. Who are they? What do they have in common? What challenges do they face? How are they coping with these challenges? What is important to them? What drives them? What are their needs?

Step 2: Define—You will analyze and synthesize the evidence collected in Step 1, prioritizing the needs that your study uncovered. What problems would benefit the businesses most if addressed, and why? At this crucial point, you will help your client choose the opportunity that would be most impactful for them to tackle.

Step 3: Ideate—You will employ ideation techniques to help a team of collaborators develop (many) possible solutions to the problem you prioritized in Step 2.

Step 4: Refine—You will assist your client in selecting an intervention idea, building a prototype, and conducting an experiment to test it out, involving the entrepreneurs to gather their feedback. Depending on the problems uncovered in Step 1, this idea may indeed involve repurposing the libraries, or it may take a different direction altogether. The feedback received may necessitate adjustments to the prototype, requiring iterative testing until the solution aligns perfectly with the needs of the entrepreneurs and the community.

Now that you have a clear idea of its process, let’s dive deeper and look at DT as a collection of tools. This will further illuminate how this innovative approach can effectively tackle complex challenges and drive impactful solutions.

Now that you have a clear idea of its process, let’s dive deeper and look at DT as a collection of tools. This will further illuminate how this innovative approach can effectively tackle complex challenges and drive impactful solutions.

Design Thinking as a Collection of Tools

The mindset of DT will have the most impact on your overall results because it will keep your team working in the spirit of human-centered design. But it is easier to understand the mindset by looking at its tools first. Let’s continue looking through the lens of our hypothetical brief from Johannesburg.

Step 0: Set Up and Get Ready

Before I discuss the details of selecting tools for each stage of the DT process, it’s crucial to lay the groundwork by considering key factors such as assembling a team and creating a conducive workspace.

Assemble a Team

For optimal effectiveness in DT, you need a diverse group of people to work on a project together. In the city example, you would likely invite economic, social, technical, marketing, and other experts to work on the project. You want to amplify bias—yes, amplify bias. You want everyone to contribute their unique perspectives. You want as much diversity of thought as you can get.

It is important to note that the DT process will require a significant investment of the team’s time, so they must be fully committed to the challenge (and likely compensated).

Groups of five or six work well, and it is best to have a facilitator for every five people in your workgroup. If you are a researcher, you may choose to invite a colleague with an innovation background to cofacilitate with you. The project lead from your client’s team could also make a good cofacilitator. Whoever you choose will need to understand the DT tools and mindsets to help the teams do the work.

Choose a Workspace

You will likely opt to work in person, as in our example of a city with low-income micro-entrepreneurs. In-person workshops can be incredibly rich and productive. But conducting your DT project online is possible. In my experience, the benefit of working online is that the work is already digitized and accessible for future projects. I also find many organizations in 2024 are very comfortable working in this way. An important caveat is that you must be very intentional during research to bring your target demographic alive. It is so much easier to understand the reality of a little township shop when you are standing in it—rather than looking at photographs.

To maximize your team’s time together, you must be prepared with a preselected set of tools.

A Space: You will need a dedicated hub with lots of wall space where your project can live for the week. The DT process produces many materials (e.g., large sheets of paper covered in Post-it notes) that build on each other and remain relevant as you move through the steps. So you don’t want to be moving between venues. The space will also set the tone for the mood and character of the group you put together. A creative and inspirational space with natural light, comfortable seating, large tables, empty walls (or large windows), and space to move around comfortably is preferable.

Preparation: The tools discussed below are printed out on large canvasses and placed on the walls.

Stationery: Post-it notes, Sharpies, and a variety of materials for prototyping. We use Post-it notes because they can easily be moved around during grouping and sorting exercises. They are also an economical, nonthreatening unit of expression. Sharpies are the only pens allowed. They force participants to think and write economically, and they have the added benefit of producing succinct ideas that can be read from a few feet away.

Online Alternatives: Whiteboard platforms like Figjam, Mural, or Miro are built for this kind of collaborative work. These have many built-in templates that are easily customizable. Some even offer artificial intelligence board builders, which can be a very good place to start. You just need to allow time to onboard the project team to your chosen platform so they are all equally fluent in using the technology.

Time and Attention: In my experience, for a challenge like this one, choosing a week and asking the project team to work exclusively on the project is more productive and energizing than enlisting the team’s part-time attention. Five full days could bring you very far in this example.

Sample Schedule

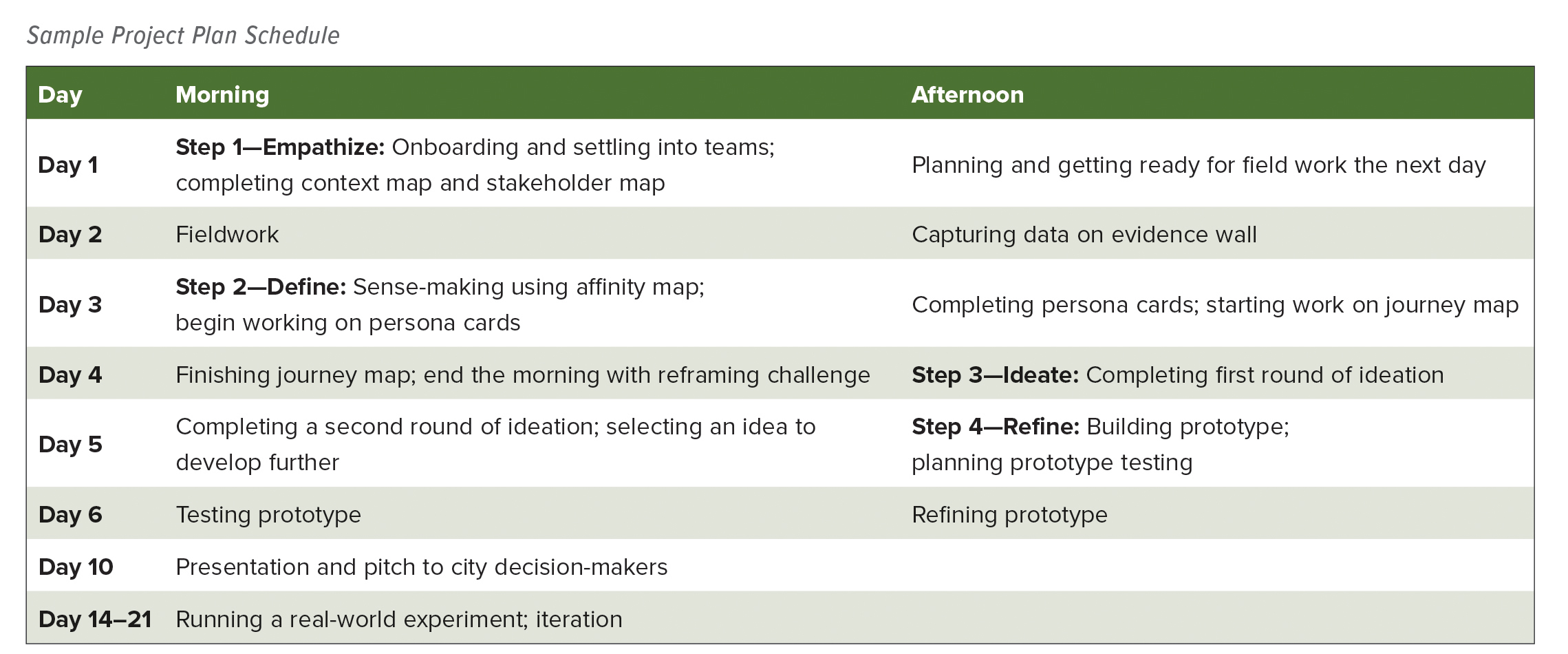

How long does the DT process take? It could take months, weeks, or days, depending on the problem, the stakeholders, the design team, budgets, the fidelity of the experiments, and changing priorities in the organization. Below is a sample project plan for our example.

If a dedicated week is not feasible for your project and you have the luxury of time, then take the schedule above and split Days one through six over a 12-week period, e.g., complete Day one’s morning activities over three and a half hours on a Tuesday and then the afternoon activities on Thursday, and so on.

If you wanted to use this process for consumer co-creation, you could run through a fast-paced version of the whole process in two hours. You can find an example of this quick-turn version of the process at www.firstpersonresearch.com/post/design-thinking-for-consumer-co-creation-groups.

Now that we’ve considered the team, the workspace, and the schedule, let’s transition into exploring the specific tools that can be used in each stage of the DT process.

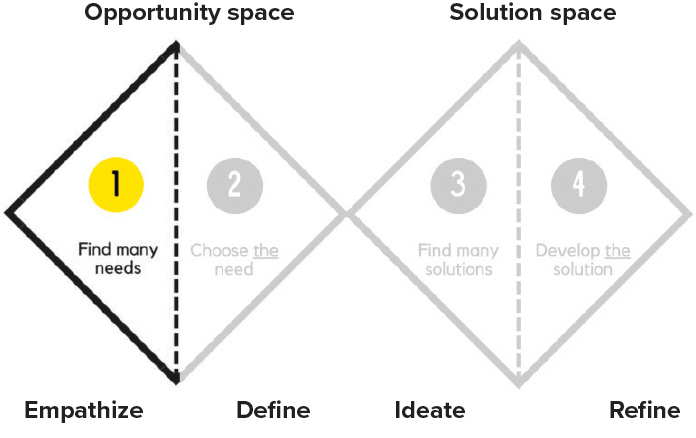

Step 1: Empathize

As we venture into Step 1 of the DT process, our primary focus is immersing ourselves in understanding the experiences, needs, and challenges of end users. To do this, we use tools that map the context of the challenge and tools that help us collect rich and insightful data.

As we venture into Step 1 of the DT process, our primary focus is immersing ourselves in understanding the experiences, needs, and challenges of end users. To do this, we use tools that map the context of the challenge and tools that help us collect rich and insightful data.

Understand the Context

Context and stakeholder maps are not essential to complete, but it would be beneficial if you have time:

Context Map: This tool helps the teams bring contextual understanding into the room. For example, they may identify regulatory, economic, and technological aspects relevant to understanding the micro-entrepreneurs in Johannesburg. An example of a context map canvas can be found at www.designabetterbusiness.tools/tools/ context-canvas.

Stakeholder Map: A stakeholder map is another useful tool in Step 1. It allows teams to identify the roles and players who impact the people we are trying to help. It can also point to stakeholders who may eventually be impacted by any intervention we plan. Additionally, the stakeholder map is a very good start to inform the sample design. An example of a stakeholder map canvas can be found at https://wrkshp.tools/tools/stakeholder-map.

Conduct Research

The most important part of Step 1 is to conduct primary research. Ideally, your project team should have firsthand experience in the field, talking to those they want to help, seeing the space in which they operate, etc. Alternatively, your client may commission a full research project with you; in this case, Step 1 will entail a presentation of your project.

For the purposes of our example, let’s assume you are able to arrange site visits and data collection by the teams that will be working on the challenge. This will enable you to use the following research tools:

Ethnography: If your project allows for immersion, choosing ethnographic methodologies over talk methodologies is advisable. If it is feasible for your team to visit hairdressers, walk the streets, buy from the businesses, etc., they should do so. This will be a valuable investment of project time, as your team will experience the sights and sounds of the environment and gain a first-person understanding of the reality they seek to influence. The quality of your output will be directly correlated to the quality of your team’s engagement with the people they hope to help.

Interviews: If ethnographic methods are not possible, talk methodologies (focus groups, individual in-depth interviews, intercept interviews) will have to do. These can take any form relevant to your project. The more firsthand input, the better. Your team needs to get as close as possible to the people you hope to help.

Diaries: Consider a diary exercise to capture granular detail on any journeys undertaken by your target demographic. A journey in our example may be a street vendor going to a wholesaler to buy stock for his shop. You should capture all the typical steps, goals, roadblocks, points of failure, thoughts, and feelings at every moment of the journey. More on that in Step 2, but remember that what you don’t collect, you can’t map later.

To ensure effective data collection during Step 1, providing training on interviewing techniques is crucial. Standard research practices, like emphasizing the use of open-ended questions and obtaining consent for photography, must be made explicit to nonresearcher colleagues.

Additionally, gathering emotive media enriches the research process by vividly portraying the users’ experiences. So, make sure the research methodology you decide on produces media like videos, photographs, and artifacts (e.g., receipts, business cards, flyers, maps) to bring the stakeholders’ world alive. These items will be useful for storytelling in the persona and journey-building exercises that come later.

For efficient data processing in shorter timeframes, consider the practicalities of a condensed research schedule. If you are doing a five-day sprint, you won’t have time to transcribe interviews and work with detailed data. You will likely only have time for intercept interviews and immersions. You will work from field notes in various notebooks, and your team will, crucially, have an embodied understanding of the lived reality of the people you are trying to help. Your team may spend a morning engaging with entrepreneurs and then spend the afternoon capturing their findings on a large evidence board (a big blank sheet of paper on a wall), one idea per Post-it note.

In sample design, prioritize extreme users to reveal insights that address the diverse needs within your target audience. Design thinkers uphold this principle because they recognize that extreme cases often highlight needs not yet articulated by the mainstream. By addressing these fringe needs, unique insights with broader applicability may emerge. For instance, include a small vendor with no credit at a wholesaler who operates on a cash basis daily, alongside a vendor with a larger business who maintains a line of credit and purchases stock monthly.

This approach ensures that you capture a comprehensive range of perspectives and uncover insights that may otherwise remain hidden.

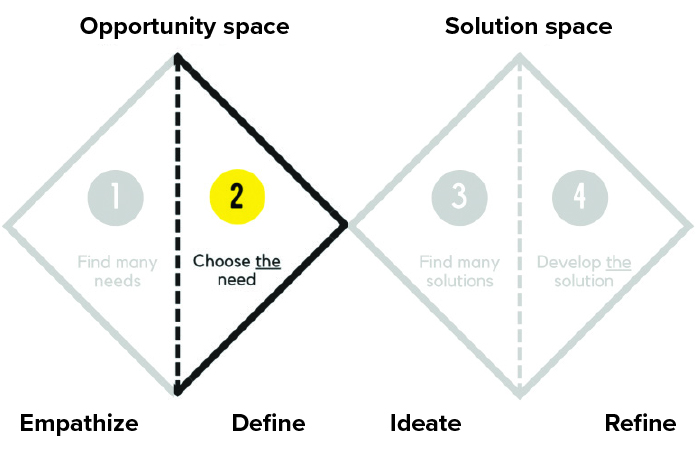

Step 2: DEFINE

The Define step is the most difficult part of the DT process for nonresearchers. Here, you are making sense of all the data collected in Step 1. We aim to synthesize this data into a coherent story that helps us prioritize the pain points we want to address. To do this, every DT project will use these four methods: affinity mapping, persona cards, journey mapping, and a reframe.

Affinity Mapping: Teams transfer findings from their notebooks onto Post-it notes, writing only one idea per note. This step acts as a revision of the data we found and brings all the information into one space. Affinity mapping is then used to cluster the findings that go together: which data points come together to produce themes. A second step is to look for causal relationships between the themes or to place the themes into a hierarchy.

Persona Cards: Teams are now ready to start working on personas. A persona card is an archetypal representation of an end user (or the person you are trying to help) observed in your fieldwork. I like to start with a quick brainstorming exercise: let’s capture all the characters we met today. Which of these are facing similar issues? Which of these are most alike? Which are most different? Could we plot them on a continuum of some kind? Once you have captured all the possible personas, your team will select two or three that offer the most intrigue and that the team feels most excited to help.

You can have a generic standard structure to your persona cards, but it will likely be most helpful to customize the persona card for every project. Persona card attributes may include higher-level goals and dreams, day-to-day personal goals and tasks, internal pain points and external hurdles, coping strategies that work for the persona, and coping strategies that create other problems.

An alternative to the persona card, the empathy map, can also be useful. The benefit of the empathy map is that it also describes the immediate environment from the persona’s perspective. You will likely only have time to complete either the empathy map or the persona cards, but you can always add persona card attributes that capture elements of the empathy map.

When you explain persona cards to the project team, I find it helpful to make them think of characters from movies or TV series that are most intriguing to watch. These characters are rarely one-dimensional; the best characters have some good and bad in them. Your personas should experience some successes but have some very real tensions. If your persona has no tension, it means you are working with a flat, one-dimensional character that just won’t be as useful in uncovering problems we can solve for.

Once you have well-defined personas, you can do a simple voting exercise to choose one persona to take further. In some projects, you may choose to move ahead with a few or all of the personas. For the purposes of this article, we will develop one persona.

At this point in the DT process, it is important to remember we are slowly working toward the end of the opportunity space. We are looking for a compelling problem that would be worthwhile to solve. Once we have decided which persona to work with, we need to take that persona on a journey to find and understand their detailed pain points.

Journey Maps: At this stage of the DT process, the journey map’s purpose is to take a pain point we discovered and tease out the story around it. What happens before, during, and after that moment? Where is the story headed? What opportunities can we find that will move the person toward their goals? What other pain points come up?

Once your team has decided which persona they would like to take on a journey, they must decide which journey to study in depth and define its timespan. Is this a micro-journey spanning a few minutes, or a longer journey?

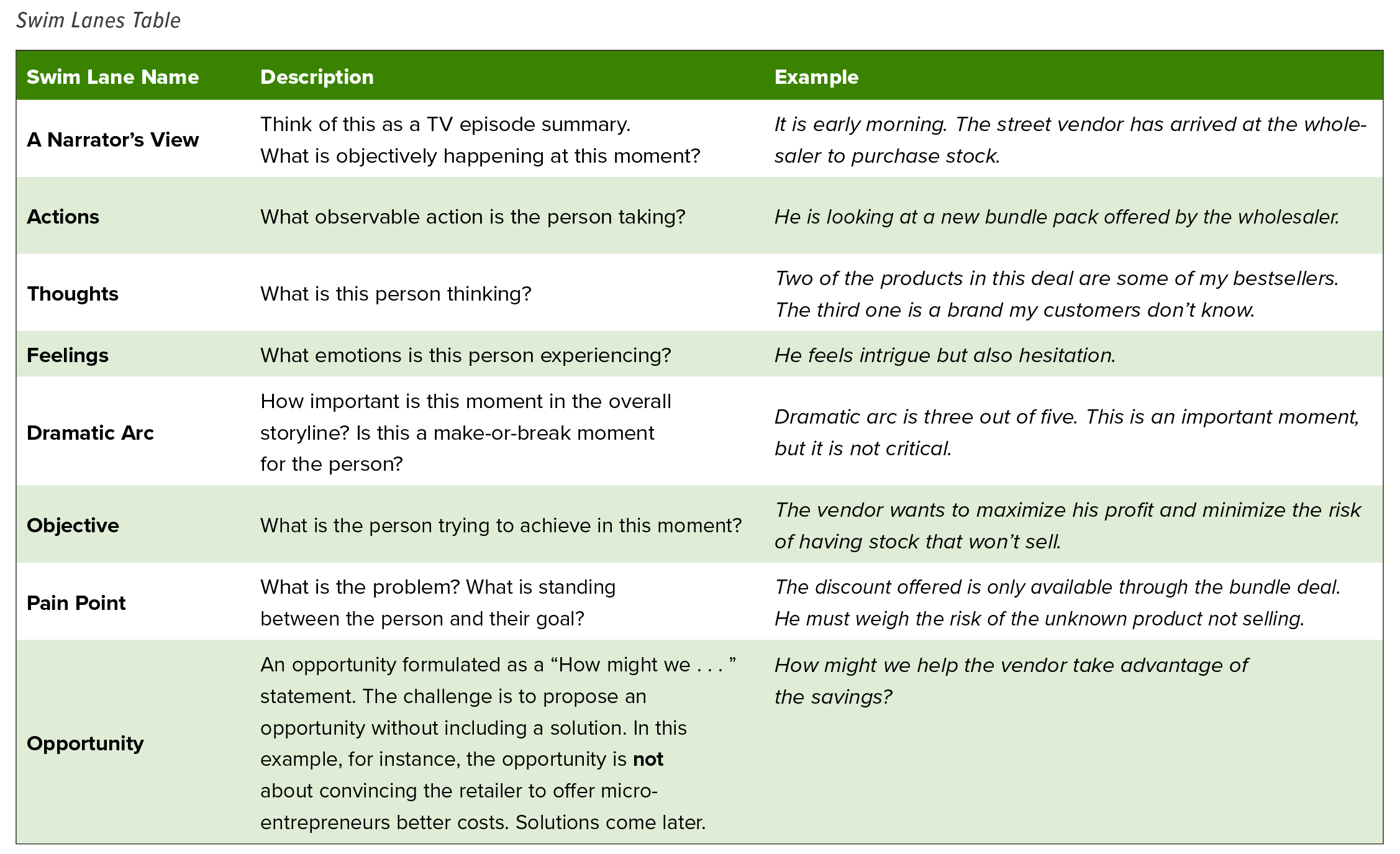

Your particular project will determine the swim lanes that your journey map will have. Typical swim lanes are:

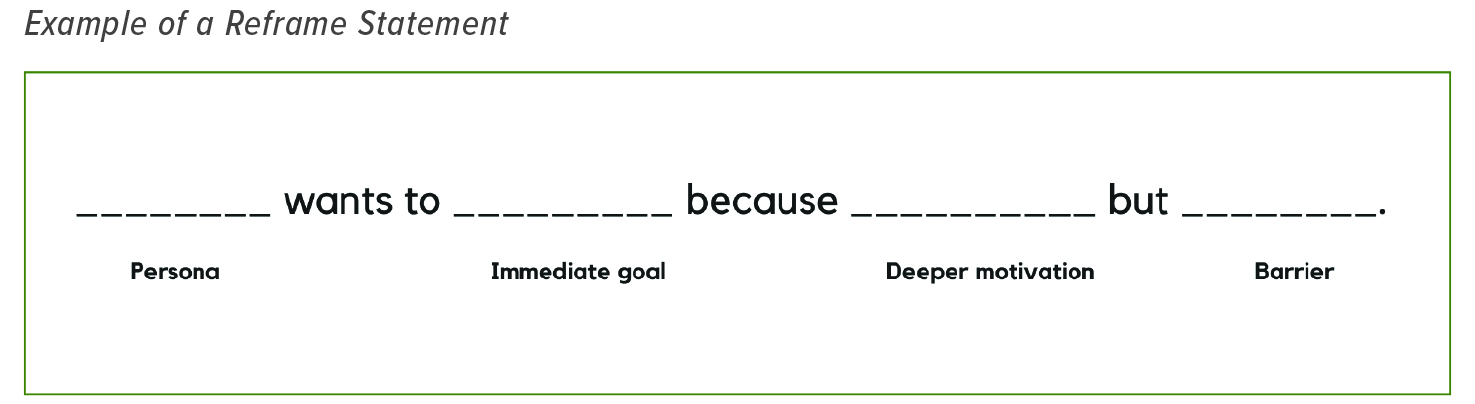

Reframe: The reframe is the culmination of all the work in the first diamond. It reformulates a key pain point that we have decided to focus on, embedded in a good understanding of the persona, the challenges faced, and the context within which we find them.

See the Reframe Statement example below, e.g., REFRAME: The street vendor who sells snacks and has many competitors wants to maximize his profit and minimize the risk of underselling stock because he buys stock daily with his sales from the previous day and does not have any cash flow buffer, but he does not qualify for special rates at the wholesaler because he spends too little at a time.

Take a moment to compare the vague problem definition we started with (e.g., Could we run a co-creation project to help the city entrepreneurs and possibly repurpose the unused libraries?) to the level of focus that we have now. Ideation for this reframed problem statement will address a very real human need that would have a significant impact if solved. That is why DT is so powerful: it creates solutions in response to a human problem worth solving.

Once you have reframed your design challenge, you are ready to begin ideating.

Step 3: IDEATE

As we start to think about the tools that can be used in the ideation phase, it’s crucial to recognize this pivotal moment in the DT process—the moment we transition from understanding the problem to generating innovative solutions. This marks a fundamental difference between DT and other creative or innovation processes. Consider Einstein’s famous quote, “If I had an hour to solve a problem, I’d spend 55 minutes thinking about the problem and five minutes thinking about solutions.” DT embodies this philosophy by prioritizing deep understanding before ideation.

As we start to think about the tools that can be used in the ideation phase, it’s crucial to recognize this pivotal moment in the DT process—the moment we transition from understanding the problem to generating innovative solutions. This marks a fundamental difference between DT and other creative or innovation processes. Consider Einstein’s famous quote, “If I had an hour to solve a problem, I’d spend 55 minutes thinking about the problem and five minutes thinking about solutions.” DT embodies this philosophy by prioritizing deep understanding before ideation.

A key thing to understand about ideation is that your team will have to come up with many ideas before you will find a good idea. Quality really does come from quantity. So, you will build multiple rounds of ideation before you select an idea to prototype in the next phase.

This is where your project will really benefit from the multidisciplinary team you assembled. Having a team in the room with widely diverse backgrounds will allow them to create novel solutions out of unique references.

Generate Many Ideas: When you dig a new well, you must pump out the muddy water before it runs clear. So you need a rapid-fire technique that gets the muddy water out of the way and permits everyone to fail. One method that could work is a “bad idea brainstorm” (race against a clock to come up with as many bad ideas as possible) or “idea popcorn” (participants stand in a circle and must come up with an idea as quickly as possible). You can do multiple rounds like this to ensure you have many ideas.

Enrich Ideas: Once we have generated many ideas, the project team can review and expand on all available ideas, combining different ones or adding to them. A useful technique in this step could be “brainwalking,” in which workshop teams get up and walk through a physical space while looking at various prompts to enrich their ideas. You will have to set up this space with prompts that are relevant to the challenge, and that will help participants expand their thinking. Prompts for our example may be large photographs taken inside neighborhood shops, photos of advertisements and signs put up around the neighborhood by brands and organizations, or items collected in the neighborhood, such as products for sale in the shops. You may also want to put up quotes by prominent neighborhood residents. In short, use any stimulus that will bring the environment of your target population into the ideation space.

If time does not allow for extensive iterations, a technique that works for generating and building out ideas is the “6–3–5”: six team members each come up with three ideas. The team then expands on each idea with five rounds of iteration.

So, when selecting ideation tools for DT, the most important consideration is to ensure they facilitate divergent thinking and encourage the generation of a wide range of ideas. The tools should promote creativity, collaboration, and inclusivity within the team, allowing for exploring diverse perspectives and solutions.

Step 4: DELIVER

Now, as we move into the Deliver phase, the rigorous processes of empathy, definition, and ideation empower us to make wellinformed decisions about which idea holds the most promise for prototyping and testing.

Three tools that could be used for prioritizing and selecting promising ideas are “sticky decision,” “the four categories method,” and “form factor.”

- STICKY DECISION: Each participant is given a limited number of dots to allocate to their preferred ideas. Participants can distribute their dots according to the perceived value or importance of each idea. After everyone has voted, the ideas with the most dots are considered the most promising and are prioritized for further development. This method encourages active participation and consensus-building.

- THE FOUR CATEGORIES METHOD: Teams categorize ideas in terms of how abstract they are: the rational choice, the most likely to delight, the darling idea, and the long shot idea.

- FORM FACTOR: Teams can sort ideas according to form factor, i.e., which ideas could work well for a digital prototype, a physical prototype, or an experience prototype.

These techniques allow teams to consider all the ideas according to various selection criteria, ensuring efficient use of resources during the prototyping phase.

Prototyping: Now, teams have to make it! Prototyping is a way for teams to “think while doing,” planning and building out their favorite idea. Here, teams may use a journey map again to create a future state journey that tells the story of how their invention will take the persona from their current problematic situation to a preferred one. Roleplaying is a great way at this stage to play out a story and see how it may develop. Teams could build an object, write a description of their idea, or build an imagined user interface. Anything to bring their idea to life.

Testing: Once teams have their prototype, it is time to test it. They need to plan who they might test it with, decide on their success criteria, and then put their prototype into the real world and see what happens. This is crucial because it allows them to stay close to their target demographic and determine if the idea will move the dial toward the persona’s goals. Teams need to iterate and retest until they get to a better- developed idea that may be worked into a real-world experiment.

Design Thinking As a Mindset

DT as a mindset goes hand-in-hand with the process and tools employed throughout the DT journey; it serves as the guiding principle that underpins every step. Throughout the DT process, there’s a deliberate emphasis on embracing ambiguity, recognizing that complex problems often lack clear-cut solutions. This acknowledgment fosters a comfortable environment for experimentation and exploration, allowing for the discovery of innovative approaches. DT advocates embracing failure as a natural part of the iterative process, viewing it not as a setback but as a valuable learning opportunity that informs future iterations. By maintaining a bias toward action, teams are encouraged to move quickly from ideation to implementation, facilitating rapid feedback loops and iterations.

Ultimately, the mindset cultivated by DT prioritizes innovation by encouraging teams to challenge assumptions, promotes adaptability by remaining open to change, and fosters continuous improvement through ongoing reflection and refinement, effectively tackling complex challenges in dynamic environments.

By embracing this mindset, teams can harness the full potential of the DT process and tools, driving innovation and delivering impactful solutions that truly resonate with their audience.

References

Parker, Haillie. “11 Effective Ideation Techniques (with Templates).” ClickUp, March 21, 2024. https://clickup.com/blog/ideation-techniques/#4-3-method-6-3-5-.

Rafiq, Elmansy. “The Double Diamond Design Thinking Process and How to Use It.” Designorate, April 3, 2023. www.designorate.com/the-double-diamond-design-thinking-process-and-how-to-use-it.

Stanford, Dawan. “A Short Introduction to Design Thinking with Dawan Stanford.” Presented and produced by Dawan Stanford, Fluid Hive. Design Thinking 101. October 2019. Podcast, MP3 audio, 24”05. https://open.spotify.com/episode/6HjzR3Kk6HcFSFfyWuF7uJ?si=8_SsBXOoSuOnPPlxBkw-Wg&nd=1&dlsi=d8da7ab67e3248d8.

Voltage Control. “8 Great Design Thinking Examples.” July 3, 2023. https://voltagecontrol.com/blog/8-great-design-thinking-examples.

Further Reading Resources

Interaction Design Foundation. “What is Design Thinking (DT)?” Interaction Design Foundation, May 25, 2016. www.interaction-design.org/literature/topics/design-thinking.

Mattson, Chris. “Design Thinking Short Course.” The BYU Design Review, April 2023. www.designreview.byu.edu/design-thinking-short-course.