By Andrew Grenville, Executive Vice President, Research, Angus Reid Group, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, andrew.grenville@angusreid.com

Have you ever come to a conclusion that made complete sense, but it later turned out to be wrong?

As humans and researchers, we’re hardwired to seek patterns and make quick decisions. But that can sometimes lead us to the wrong conclusion.

In medicine, incorrect assumptions can have fatal consequences. In policing and law, it leads to wrongful convictions. In insights, wrong conclusions can result in inappropriate advice that harms our clients’ businesses.

One way to avoid these pitfalls is to adopt two reliable strategies: diversity and doubt. By seeking out diverse perspectives and questioning our assumptions, we can gain a deeper understanding and arrive at more meaningful insights.

In this article, we’ll explore how other types of sense-makers—outside of market research—put into practice diversity and doubt strategies to battle unconscious bias.

By sense-makers, in this article, I mean doctors, lawyers, detectives, intelligence analysts, forecasters, and scientists of all stripes. Just like insights professionals, they gather information, make sense of it, and then figure out the next steps.

After millennia of trial and error and a more recent scientific study of ways to improve decision-making and insight generation, these sense-makers reveal three methods for battling bias.

Three Ways to Battle Bias

Teamwork: Getting other people’s perspectives is the only way to find our blind spots and a very effective method for checking to see whether we have leaped to faulty conclusions. In medicine, we see this in hospital rounds and peer reviews.

Doubt: Research by decision scientists suggests that questioning your assumptions and trying to disprove them is almost as effective in bias-busting as getting another person’s take on your problem.

Checklists: Employing teamwork and doubt is effective, but you also need a process that prompts you to employ these tools. A checklist can be an important part of that process.

Our Brains Are Pattern-Seeking Machines

Before we dive into these solutions, it is important to understand just how deep-rooted our biases are.

“Our brains are belief engines: evolved pattern-recognition machines that connect the dots and create meaning out of the patterns that we think we see,” writes Michael Shermer in his book, The Believing Brain. “We are the descendants of those who were most successful at finding patterns.”

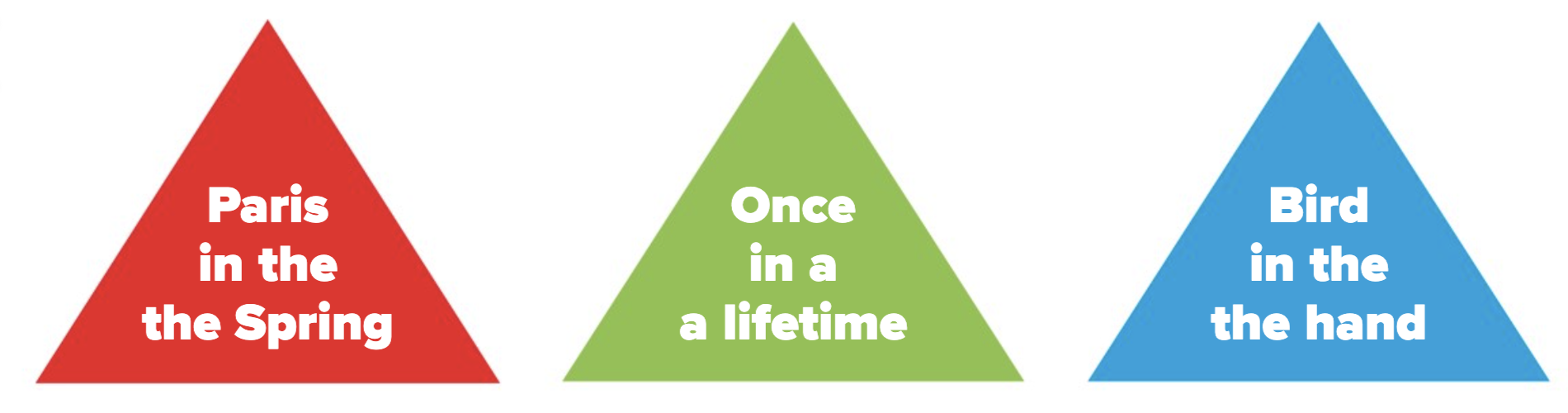

We use patterns, and expectations of patterns, to work efficiently with the information we perceive. Read the phrases in this diagram.

Simple, right? Paris in the spring. Once in a lifetime. Bird in the hand.

But look more closely at the text in the triangles: the articles “the” and “a” appear twice in each phrase. Our brains focus on the expected sequence and ignore the evidence that doesn’t fit that pattern.

But look more closely at the text in the triangles: the articles “the” and “a” appear twice in each phrase. Our brains focus on the expected sequence and ignore the evidence that doesn’t fit that pattern.

In addition to ignoring information that does not fit our preconceived notions, we are also wired for confirmation bias, which the Oxford English Dictionary defines as the “tendency to seek or favor new information which supports one’s existing theories or beliefs while avoiding or rejecting that which disrupts them.”

Confirmation bias is not newly discovered. It was what Julius Caesar was talking about when he said humans, “In general, are quick to believe that which they wish to be true.”

It is relatively easy to spot confirmation bias in others. Have you ever been to a focus group where the product manager complains that these participants “are not the right people” when the participants say things that run contrary to their expectations? Or seizes on the one thing that confirms their assumptions while ignoring the rest of what was said? It happens all the time.

But seeing confirmation bias in others is much simpler than seeing it in ourselves.

We need to learn strategies to identify where, when, and how bias affects us. But that is exceedingly difficult to do on our own. That’s why teamwork is such a powerful tool in battling bias.

Teamwork: Diverse Teams Make the Difference

Diversity is the key to using teamwork to battle bias.

The best teams bring together people with different backgrounds, experiences, and abilities. Input from people with unique perspectives is important because it helps us shatter “in-group” shared assumptions and shines a powerful light on a particular group’s blind spots.

“When people with heterogeneous backgrounds work together, their perspectives emerge in different ways, allowing more knowledge and solutions to emerge,” writes the National Research Council in their report, Intelligence Analysis for Tomorrow: Advances from the Behavioral and Social Sciences.

The council goes on to say: “Diversity can be sought in subject-matter expertise, functional background, personal experience, and mission perspective. Such sharing allows analyses to be richer and deeper, with better-understood strengths and weaknesses, whereas individuals working in isolation are more limited by their assumptions and myopic about the limits of their knowledge.”

As researchers—often working remotely or as solo practitioners—this can be challenging. It requires us to make an extra effort to reach out.

An ideal approach is to draw in perspectives from people across the organization sponsoring the research. Sales, CX, operations, front-line staff, and many others all offer great reality checks and additional insights because their perspectives differ from your own.

Perhaps you can pull the extended team of the sponsoring organization for 45 minutes for an insight innovation meeting where you share your findings and ask for questions, critiques, and alternative perspectives. If your team is too short on time, ask members individually for a 10–15-minute call to tap into their unique expertise; this way, you’re taking a limited block of time from any one person and can allow more flexibility for their calendar.

Sometimes the sponsoring organization isn’t open to this kind of collaboration, sadly. In cases like this, the next best thing is to seek out different perspectives on what people have written on the topic or issue. Reviews, industry articles, articles in the press, and social media scraping can all be useful. It is important to ensure you have the perspectives of both fans and critics. Diversity is what’s most valuable.

Yes, getting the input of a team takes effort. But what is the cost of leaping to the wrong conclusion or being blind to a crucial aspect of the problem? Can we afford to not tap into a team? I doubt it.

Doubt: Forcing Yourself to Take a Different Perspective

Doubt seems negative. But its effects are incredibly positive. “Doubt is an uncomfortable condition, but certainty is a ridiculous one,” said Voltaire.

Doubt of the sort we are discussing depends on metacognition, which is about having awareness and insight into our own thinking.

Doubt with metacognition has proven lifesaving in medicine.

Drs. Eoin O’Sullivan and Susie Schofield, in the article, “Cognitive Bias in Clinical Medicine,” wrote: “Forcing clinicians to ask themselves, ‘What else could this be?’ is a form of metacognition and may force one to consider ‘why’ one is pursuing certain diagnoses and consider important alternative scenarios. There are a number of positive studies supporting the role of metacognition in improving decision-making.”

Thinking twice has also been proven to increase the accuracy of intelligence forecasts of world events.

Philip Tetlock and Dan Gardner in Superforecasting report that “merely asking people to assume their judgment is wrong, to seriously consider why that might be, and then make another judgment, produces a second estimate which, when combined with the first, improves accuracy almost as much as getting a second opinion from another person.”

Employing doubt clearly has its benefits.

But remembering to consciously enact doubt is harder than it seems. That’s where checklists come in handy.

Checklists: Battling Bias through Process

Checklists are deceptively simple. Indeed, they need to be straightforward and streamlined to stand up to repeated use.

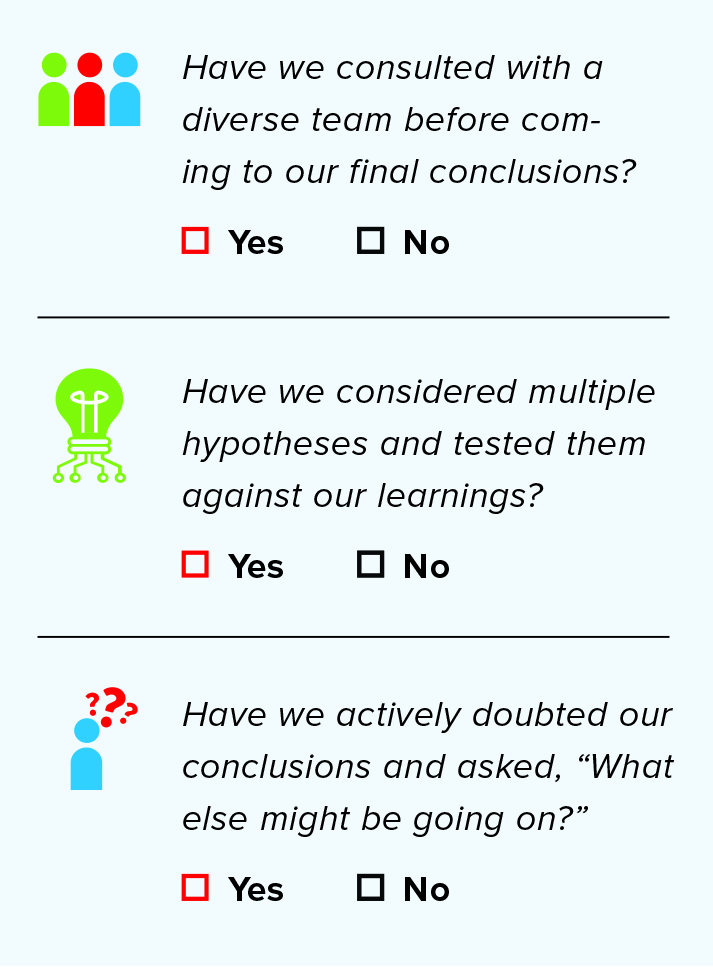

Here is a simple checklist that, when employed, reminds us to doubt and to engage with diverse teams.

If we can say “yes” to each of these simple questions, we can be even more sure that our learnings will help and not hinder our clients.

You might think to yourself: “Seriously, though, a checklist, really?”

A checklist can seem like an insult. Merely suggesting that there is value in forcing yourself to answer some questions suggests we’re not up to the task without the checklist.

That’s what prominent surgeon Atul Gawande thought.

Gawande, also a public health researcher and writer who authored The Checklist Manifesto: How to Get Things Right, has become well-known for his work on improving healthcare systems, patient safety, and surgical outcomes through the use of checklists.

Gawande’s research highlights the importance of using checklists to ensure that critical steps are not missed, which can help researchers avoid errors and improve the accuracy of their data. By emphasizing the value of teamwork and collaboration in the use of checklists, Gawande’s work encourages people to work more effectively and efficiently as a team.

While Gawande had seen enough evidence to convince him of the value of checklists, when he started out, he had some doubts about the worth of a checklist in his own personal practice. In his own words:

“In the spring of 2007, as soon as our surgery checklist began taking form, I began using it in my own operations. I did so not because I thought it was needed but because I wanted to make sure it was really usable. Also, I did not want to be a hypocrite. We were about to trot this thing out in eight cities around the world. I had better be using it myself. But in my heart of hearts—if you strapped me down and threatened to take out my appendix without anesthesia unless I told the truth—did I think the checklist would make much of a difference in my cases? No. In my cases? Please. To my chagrin, however, I have yet to get through a week in surgery without the checklists leading us to catch something we would have missed. Take last week, as I write this, for instance—we had three catches in five cases.”

As loath as I am to admit it, my use of checklists is like Dr Gawande’s. I think I have already internalized these questions. But when I stop and honestly ask myself the checklist questions, I almost always realize I could go deeper or do better in answering “yes” to at least one of them.

Try a checklist and find out for yourself.

Battling to Better Insights

Generating an insight is never as straightforward as it might seem. As we have seen, bias is a slippery and powerful force. Its effects are easily missed—unless we purposefully seek them out.

Diversity, doubt, and checklists are essential tools for professionals seeking to generate meaningful insights. By working in teams with people from different backgrounds and perspectives, we can avoid group blind spots and better understand the strengths and weaknesses of our analyses.

Questioning our assumptions and employing checklists can also help us avoid confirmation bias. While seeking out diverse perspectives and questioning assumptions takes time, it is worth the effort to avoid leading our clients to the wrong conclusion.

Next VIEWS Issue: Second in a Two-Part Series

Building a Process for Generating Eureka Moments

Battling bias is a defensive aspect in the process of generating insights. We have learned from other sense-makers how to use teamwork and doubt to root out errors and point the way to fresh perspectives. But there are other things we can learn from them, too.

In the next article in this series, we look to the history of science to provide us with a roadmap for how to generate better insights. The hunt for deeper insights is not new, and it is not unique to our type of research. We’ll be diving into a time-tested five-step process for generating eureka moments.

References

Shermer, M. (2012). The Believing Brain: From Ghosts and Gods to Politics and Conspiracies—How We Construct Beliefs and Reinforce Them as Truths. New York, NY: St. Martin’s Griffin.

Heuer, R.J. Jr. (1999). Psychology of Intelligence Analysis. Washington, DC: Center for the Study of Intelligence, Central Intelligence Agency.

National Research Council. (2011). Intelligence Analysis for Tomorrow: Advances from the Behavioral and Social Sciences. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Tetlock, P.E., & Gardner, D. (2015). Superforecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction. New York, NY: Broadway Books.

O’Sullivan, E.D., & Schofield, S.J. (2018). Cognitive Bias in Clinical Medicine. Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh, 48(3), 225-232. doi: 10.4997/JRCPE.2018.306.

Gawande, A. (2009). The Checklist Manifesto: How to Get Things Right. New York, NY: Picador.

1 Trackback / Pingback

Comments are closed.