By Robert Walker, CEO & Founder, Surveys & Forecasts, LLC, Norwalk, Connecticut, rww@safllc.com

To keep growing, both startups and established brands need a new product pipeline. One of the tools that can be used toward that goal is idea screening—the process of evaluating new product ideas at an early stage to help identify promising ideas for future product development. Idea screening should not be thought of as a single-siloed process: qualitative approaches are also essential to feed the idea-screening process. However, qualitative researchers should have a good understanding of what happens after their work has ended.

Quantitative idea screening helps to identify the most promising early-stage opportunities and accelerate them to the next phase of new product development. This could take the form of a minimum viable product, a new formulation, or a line extension. Simply put, taking a systematic approach to idea screening helps a company align scarce marketing resources to the candidates with the most market potential. This article describes an approach that qualitative researchers can use to help their clients build a systematic way to identify new product opportunities. We will outline a practical framework using a set of standard measures. Larger organizations and funding mechanisms (i.e., venture capital firms) use this approach—but it is not only limited to companies with deep pockets. Smaller companies can use this approach, too.

What is the Role of Idea Screening?

What is the Role of Idea Screening?

Idea screening is a structured way to simultaneously evaluate many ideas and identify those with the greatest potential for success. Idea screening can be used to evaluate vastly different ideas or ideas within a certain category. This process can also be used to identify general areas where consumer needs are not currently being met. Unlike concept testing (which attempts to evaluate more fully developed advertising concepts with detailed language, images, pricing, or other marketing mix variables), idea screening focuses on the appeal of basic ideas using a limited set of measures. This allows researchers to quickly see which ideas warrant further investment or not.

- For startups, idea screening offers a way to prioritize options, ensuring that those with broader appeal move forward. For example, a personal care start-up might have developed a patented eco-friendly formula. This ingredient could be used in many categories (e.g., hand lotion, hair care, personal hygiene). Screening multiple category ideas, each based on this novel ingredient, is a good use case for idea screening. The results can then be used to guide both R&D and marketing strategy before additional investment in prototypes or packaging is needed.

- Established brands, on the other hand, might use idea screening to extend product lines or expand into adjacent markets. In these cases, alignment with an existing brand’s equity (also called “brand fit”) will be important. For example, a global beverage brand considering a low-sugar line product can screen ideas to see which flavors, packaging, or positioning best align with current brand perceptions.

How Do I Design an EFFECTIVE IDEA-SCREENING Process?

As a qualitative researcher, you already have good visibility into the new product development process. After all, you conducted focus groups or in-depth interviews that identified possible new product opportunities. But what should the client do next if there are multiple competing ideas?

First and foremost, introduce the idea of screening those many ideas, and use a more systematic approach—especially one that relies on consumer or buyer input to help the company prioritize new product development efforts.

Here are four foundational elements to get your idea-screening journey off the ground:

- Obtain Management Buy-In

Whether you are dealing with a solopreneur, a start-up, or a mid-to-large organization, management must agree that this approach will be used to identify new product priority areas. By “buy-in,” we mean that management agrees to the process and agrees to deploy the needed resources for product development once the results come in. Absent top management support, the best ideas can be overlooked or deprioritized, leading to missed opportunities.

- Define Your Success Criteria

Establishing clear objectives is critical to the success of an idea-screening process. Start by defining what success will look like. For example, do you want to find ideas with the highest purchase interest, or is it more important to find distinct ideas that fill a gap in the market? A startup might prioritize broad consumer appeal, while an established brand might focus on ideas that align with its image. Setting “go/no-go” criteria based on benchmarks or previously tested ideas can also ensure that a winner is defined properly and passes basic performance criteria.

- Standardized Stimuli

In idea screening, the stimuli must be descriptive but also very simple. At the early idea stage, ideas can be thought of as “nuggets,” with just enough information to convey the idea without excess detail. A brief written description with (or without) a visual representation will suffice. The goal is to get a consumer to focus on the product’s main attributes. All ideas, however, must include an end benefit. That is, what will the buyer receive from the product or service they just read about? Remember, we are not screening two or three ideas—we are often screening 10, 20, or more.

Here are some very simple hypothetical examples of idea “nuggets” that could be put into an idea-screening research study:

- The Energy You Need, Naturally. Powered by 100% plant-based ingredients for a clean energy boost, this energy bar keeps you going throughout the day without the jitters or a crash.

- The Cleaner That Does It All. This multisurface cleaner is safe for wood, glass, and countertops, simplifying your cleaning routine with one product for every room.

- Stay Cool Anywhere, Anytime. This portable fan has a rechargeable battery and a sleek, compact design, providing refreshing, on-the-go cooling that lasts for days.

Concise, focused stimuli will keep the evaluation clean, consistent, and reliable. Depending on the total number in your study, the ideas can include more detail, but clarity is key: make sure to have enough detail to explain the idea but not so much as to confuse respondents, slow things down, or skew the results. Generally, price is not included in idea screening because the goal is to screen the basic premise of the idea before setting a price.

- Consistent Sample Definition and Statistical Precision

Locking in the appropriate sample definition is essential for obtaining reliable results across ideas and, importantly, over time if your approach will be used on an ongoing basis. For broader-appeal products, a general population audience sample is appropriate (i.e., balanced on males/females, ages 21–64, and geographically representative). For niche ideas, such as a high-performance running shoe or users of nutritional supplements, a “booster sample” may be needed (i.e., ensuring there are large enough samples of important subgroups, such as runners or people who take B vitamins). The analysis will benefit by yielding relevant feedback from a large enough sample. Although there are no hard rules, we recommend feedback from a sample of at least 250 respondents per idea to strike a balance between precision and cost.

What Are Evaluative Versus Diagnostic Measures?

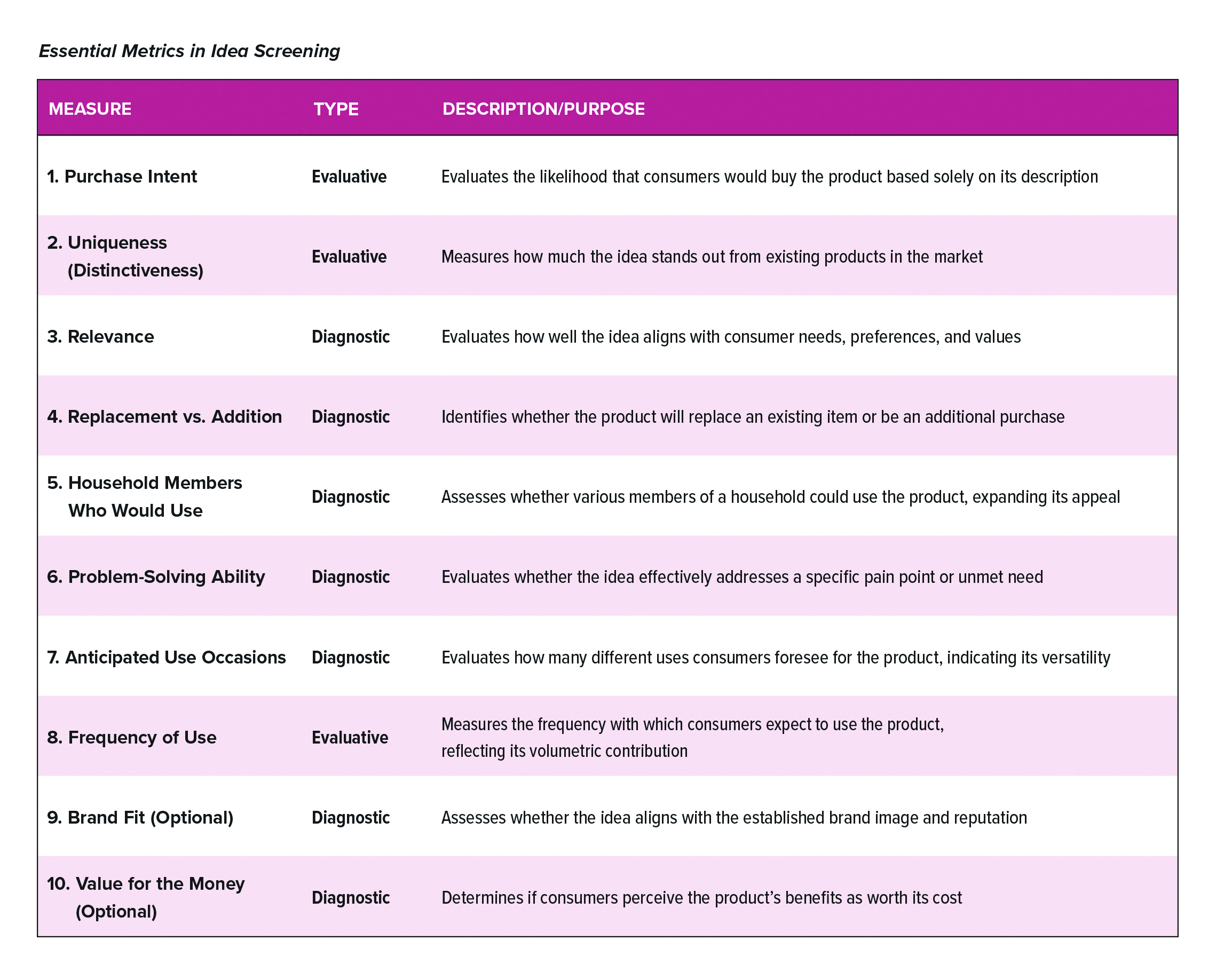

Including both “evaluative” and “diagnostic” measures allows for a well-rounded analysis that captures consumer appeal and areas for improvement. What are the differences between these types of measures?

Evaluative Measures

Evaluative measures assess performance and represent a person’s intended behavior. Examples of evaluative measures include purchase intent, intended frequency of use, and expected use occasions. These measures represent what the respondent intends to do based on the stimulus you have exposed. Although evaluative measures are critical to include because they assess performance (i.e., they address “how big is the opportunity”), they don’t necessarily explain why one idea performs better than another. For that, we also recommend including “diagnostic” measures.

Diagnostic Measures

Diagnostic measures explain why consumers feel a certain way about an idea and help to identify strengths and weaknesses. Diagnostic measures can be used to enhance or refine a promising idea that may be missing some key support points. For instance, an idea with high purchase intent but low distinctiveness (uniqueness) might indicate that a large opportunity exists but that its core selling proposition may not be defendable against competitors. Including open-ended verbatim comments or exploratory questions (while certainly valuable in later stages) should generally be avoided in idea screening because of the extra time required.

What Measures Should I Use?

Evaluating an idea’s potential appeal requires us to focus on a set of key measures that highlight interest, differentiation, and benefits. Here is a breakdown of 10 key metrics we recommend in idea screening:

Purchase Intent

Purchase Intent

Purchase intent assesses whether consumers would buy the product based solely on its description. This metric is a relatively strong predictor of potential demand and in-market performance and serves as the primary evaluative measure. This question is typically asked, “How likely would you be to buy this product assuming that it was available where you shop and sold for a reasonable price?”

- Distinctiveness

Distinctiveness (also sometimes asked as “uniqueness” or “new and different”) measures whether an idea stands out from competitors. For startups, distinctiveness can be a make-or-break factor: a new beverage brand entering a crowded market, for instance, needs to differentiate itself based on distinctive features, like excessive caffeine (for example, Red Bull) or innovative packaging. This question is typically asked, “How unique or different do you consider this product to be when compared to other products currently on the market?”

- Relevance

This measure evaluates how well the idea aligns with consumer needs and values. A relevance question would use an agreement scale with phrasing such as “This is a brand for someone like me.” For new brands, relevance is critical in ensuring that a product dovetails with the intended buyer’s mindset or philosophy. For example, a skincare company might focus on ideas that cater to consumers’ eco-friendly desire for all-natural ingredients, aligning brand identity with buyer values.

- Replacement Versus Addition

This metric identifies whether the idea replaces an existing product or serves as an additional purchase. This measure also reveals the consumer’s expected usage patterns for the product. This question is typically phrased as, “Would you expect to use this product to replace an existing product, or would you use it in addition to products that you currently use?” A replacement product suggests that it meets current needs but offers improved features, performance, or convenience. A product used in addition to other brands may indicate a niche product, special use occasions, or perhaps that it fulfills both existing and untapped needs.

- Household Members Who Could Use the Product

Broad household appeal can increase purchase potential. This question is typically asked, “Who in your household, including yourself, is most likely to use this product?” For example, a company making family-friendly meal kits would want to know who in the household sees themselves consuming the product. All things being equal, a product with broad household use would receive a higher rank than products with narrow household use.

- Problem-Solving Ability

Problem-solving ability assesses whether the idea effectively addresses a specific pain point. A tech startup might test if their productivity app helps users balance work and personal tasks, providing a clear, targeted solution that could enhance consumer interest. This question can be phased as, “Does this product solve a particular problem for you that other products currently do not?”

- Frequency of Use

This measure captures the anticipated frequency of use. This is typically asked, “How often do you think you would use the product you just read about?” followed by a frequency scale. Products that consumers expect to use more often tend to generate stronger appeal and justify their value more effectively. Breadth of use (above) is combined with frequency of use to assess overall use opportunities.

A product can succeed either by broad but infrequent use or by narrow but heavier use.

- Anticipated Use Occasions

Anticipated use assesses the versatility of the idea across different use occasions. This is typically asked, “Which of the following occasions would you be likely to use the product you just read about?” Depending on the category, we would want to explore how consumers will use the product—for example, in a daily routine or just for special occasions. By identifying potential applications, companies gain insights into the product’s relevance and marketability across different consumer needs and contexts.

- Optional: Brand Fit (Assumes a Parent Brand)

When testing new product ideas under an existing brand name, brand fit is important to know. Line extensions should not dilute or damage an existing brand’s equity. For example, a luxury fashion brand might want to explore wellness ideas to complement its premium image. Assessing brand fit means that we want to understand how well the brand extension aligns with the parent brand’s image and reputation. Conversely, some brands can compete in multiple categories if the company’s brand equity extends that far (e.g., Honda cars, generators, and robotics).

- Optional: Value for the Money (Can Be Asked With or Without Price Being Shown)

Value perceptions weigh a product’s perceived benefits versus its price. This is especially relevant in competitive categories or among price-sensitive consumers. A startup offering premium organic snacks, for instance, might test whether consumers find the product’s higher price justified by its perceived health benefits. Obviously, asking a value for the money question without a price being shown is generally not recommended; hence, this question would typically be included only if pricing were stated. However, a question about the expected price could also be considered.

Scoring of Concepts

Scoring of Concepts

While all of the above measures are important, the three most important measures are purchase intent, uniqueness (distinctiveness), and the anticipated frequency of use. Together, these measures capture the essence of each idea’s performance. In some situations, when there are many ideas being considered, you may want to consider some form of scoring to identify those that show more relative strength. To accomplish this, weights would be assigned to each measure of interest, and an aggregate score calculated. Assuming we limit this approach to the three core measures mentioned, a possible approach would be to assign a weight of 0.6 to purchase interest, 0.2 to uniqueness or distinctiveness, and 0.2 to the anticipated frequency of use. This can be calibrated to a 0–100 point scale, and then a relative ranking then calculated.

Summary

Qualitative researchers can play a critical role in helping their clients identify new product ideas by designing and conducting idea screening. When strategically designed, idea screening provides a systematic data-driven approach to identifying promising new product ideas. By combining qualitative insights with quantitative measures and benchmarks, companies can prioritize the ideas with the highest potential. From there, they can refine their innovation pipeline and optimize resource allocation. This approach can be used by startups and established brands alike to make smarter, more efficient product development decisions.