By Zoë Billington, UX Research & Customer Insights, Los Angeles, California, zbillington@gmail.com

By Zoë Billington, UX Research & Customer Insights, Los Angeles, California, zbillington@gmail.com

This quarter, Zoë spoke with Glenna Crooks, PhD. Crooks is a social scientist turned policy strategist who solves health and well-being problems for governments and organizations globally.

Strategic Health Policy International, Inc.

The NetworkSage

glenna@glennacrooks.com

Zoë Billington: Let’s start off with the 10,000-foot view of your career. How do you tell the story of how you got to where you are today?

Glenna Crooks: I’m currently in my eighth career and about to launch my ninth. I’ve worked in government and industry but I’m an entrepreneur at heart, so I founded my own strategy firm. The common thread that runs through it all is my ability to organize chaos and tackle complicated problems, often in high-stakes situations.

I started as a School Psychologist trained to be a system change agent rather than just to test and label kids. At that time, children with special needs didn’t have a legal right to an education, so many were not in school. I found them, figured out how they learned, taught that to their parents and teachers, and got them mainstreamed in classrooms. The process I developed got noticed by the state’s Department of Education and eventually, when laws established the right of all children to an education, it became the model for today’s individual education plans, or IEPs. That work was frustrating, though. By the time I saw a five-year-old, it felt too late to help them. That led me to healthcare because it was the first system to impact a child’s life. Once I was there, I never went back to education.

Zoë: Although you didn’t call it ethnographic research, it seems like that’s what you did to help these kids. I’m wondering if there’s anything that you learned from that experience that could apply to our readers’ corporate, consultative, or academic research practices.

Glenna: I never thought of it that way, but you’re right. My natural leanings towards ethnographic inquiry come from my undergraduate studies in the social sciences. A bad case of School Psych burnout drove me back to school for a doctorate. That’s when I learned grounded theory methodology. Quite accidentally, and not knowing how valuable it would be later, I started a meditation practice that honed the ability to observe without judgment. I credit those years with teaching me the skills I’ve used since. I learned lessons about the limits of our observational methods. I continue to be fascinated by that and how we filter out meaningful data and don’t see something right before our eyes.

Here’s a dramatic example. I was a passenger as my husband drove on a two-lane rural highway when I spotted a toddler up ahead in our lane. My husband didn’t see him, nor did he react when I screamed, “There’s a baby in the road. Watch out, there’s a baby!” Lacking a frame of reference for toddlers on highways he, quite literally, didn’t see it until I punched his arm and screamed again. The good news is, we stopped in plenty of time, the dad got the toddler to safety and there was no oncoming traffic.

I’ve heard something similar about when Columbus landed in the new world. Apparently some Native Americans, lacking a frame of reference for ships that large, didn’t see them. I see examples of this in market research, especially since my recent network mapping helped me understand our lives through that new lens. Pardon the pun, but I don’t think we give our tendency for “selective attention” enough “attention.” When Shawn Achor asked Harvard students to draw Harvard Square from memory, building sizes were based on the subjective importance to the student, not the objective reality of the architecture. For example, if they were not very studious, they didn’t draw the library. Why? They all missed the non-student housing that ringed the campus. Why? Why do physicians not see a dolphin image superimposed on an x-ray? Are we that subjective and is our observation that selective when we observe research subjects?

What does this mean for qual researchers? I think it applies to quant researchers too, but it’s more important for qual because qual creates many of the frameworks that we use later for quant inquiries. Any distortion caused by faulty or limiting frameworks at the qual stage will be magnified in quant stage. In order to do qual well we need to acknowledge we may be “blind” and not “see” something meaningful we don’t expect to be there. You may have seen a video that allows people to experience that: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vJG698U2Mvo).

Zoë: Your work on networks might be a new concept for readers, and one that you’re really pioneering. So how about we talk about your work on networks and how you got into that?

Glenna: The most interesting things I’ve done come from problems that clients toss my way, and exploring networks is the best example. Back in 2005, after long dinners and a second glass of wine, I started noticing a shift in what people said. They didn’t mention kids or upcoming vacations anymore. They let their hair down and said life was too complicated and they wanted to quit. Some even cried. I had to admit, I knew how they felt. I’d burned out a number of times. Worse, it seemed that each time it happened, it got harder to recover. All the yoga, fitness, relaxation, and time management I did were necessary, but not sufficient, so I went looking for what I was missing.

I found it in 2008 in an unlikely place from an unlikely person because I’m a fan of action flicks and superheroes. The trailer for the first Iron Man had come out, and I noticed an interview with Robert Downey, Jr. in a fashion magazine that same week. In it he said he had a “pit crew” of people helping him: a yoga teacher, a sensei, a psychiatrist. He said, and I quote, “I need a pit crew because, after all I’m not a Model T, I’m a Ferrari, and it takes more of a pit crew to keep us on the road.” I must have been in a snarky mood because I thought to myself, “Buster, if you’re a Ferrari, I’m at least a Maserati.” Then, I thought, “You’re right. It does take a pit crew – who’s mine, and how are they doing?” Later, I realized I was on other people’s pit crews. I never actually had the courage to ask how well I did, but I knew I’d let people down, usually because others I counted on had let me down.

I had looked at pit crews before, but only for my work life. A coach suggested I make a list of everyone I managed as a business owner. At the time, it never occurred to me to do something similar with my personal life, but now it did. I put a blank sheet of paper on the kitchen counter and started keeping track. Weeks later, when I finished there were 147 people on the list, ranging from my mom to my hairdresser. My first thought was, “Am I high maintenance or what?!” That helped me realize the problem my clients faced, because compared to them, I had a simple life. I didn’t have a spouse then, so there were no in-laws or his colleagues or friends on my list. I didn’t have kids, so no teachers or coaches or orthodontists or soccer moms. My elderly mom was healthy; she didn’t need me for anything other than fun and love. I didn’t have a dog or a cat. If I felt symptoms of burnout with 147 connections, no wonder my clients – with many more connections than me – felt overwhelmed.

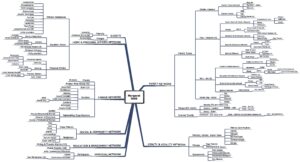

I became my first research subject and used analytic and data visualization tools to study my connection workload. Given my government and corporate experience, it’s no surprise that my initial data display was an org chart. It sure felt neat and tidy until a year later when it dawned on me that I was not a corporation with multiple divisions, I was a person with 147 direct reports. I offloaded as much as I could by hiring someone a few hours a week to do things for me, such as taking my clothes to and from the dry cleaner, going to the post office, and grocery shopping. Not doing these chores myself gave me an entire Saturday in the garden, which is where I do my best thinking. My life improved. Friends noticed I was different and asked what I was doing. Some of them gave it a try and several had even more stunning results than me. As it turns out, focusing on our personal life had a massive, positive impact on our career life. They encouraged me to keep going and my adventure in understanding networks was off and running.

Zoë: Where are you today in your exploration?

Glenna: It’s now 15 years later. I spent the first ten mapping the lives of 700 working adults during which I identified 7000 distinct types of person-to-person connections. I started with lists and though that’s better than nothing, lists are not great management tools, which is why I eventually organized the data into networks. To determine what they’d be, I had two criteria: they needed to make intuitive sense and the social science literature needed to validate that they addressed our important needs as humans. I was well into my research when Sir Robin Dunbar published his now-famous essay noting that 150 connections was the limit we can manage well and Nicholas Christakis published his research about how networks influence us. Their work and mine are beautifully complementary.

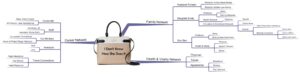

My network information architecture includes major types of networks. Life Networks are enduring. The people in them remain there for a long time. Event Networks are episodic. The people in them are there for a narrow purpose and for a limited time, like those who help us have a wedding, buy a home, or recover from storm damage. When Life Networks are supportive and we experience an event, we’ll have better outcomes because our connections will be there to offer us information, referrals, and helping hands. When our Event Networks are good, we’ll manage them better and preserve the relationships with those in our Life Networks.

During a lifetime we can have hundreds of Event Networks. However, we have only eight Life Networks. I call the first five Birthright Networks because we were born into them. Our parents created them for us and though they change over time we never outgrow what these networks are built to provide. I call the next three Life Networks Coming of Age Networks, because we mature into them.

As this work evolved, the data visualization I came to like best was a mind map. That’s because it was a better representation of reality. The person is at the center, with all their connections arrayed around them, all organized by network.

Zoë: Can you share some examples of how others have used their network mind maps to transform their lives or others’?

Glenna: My only goal at the start was to help talented people remain in the workforce, and I’m pleased to say it worked. At the 10-year mark, I told their stories in The NetworkSage: Realize Your Network Superpower. It describes a three-step process I call ACTSage. In the first step, people become Aware of their connections. In the second step, they Clarify what they need and want from these connections. In the third stage, they Transform their networks based on what they’ve learned.

Nearly everyone downsized. Some withdrew from community leadership or volunteer roles to focus on their family or career. Others opted for picnics and potlucks rather than dinner parties, which are tougher to pull off after a long week of work or travel. Some dropped social media. Everyone found gaps to fill, like a man who hadn’t replaced the dentist who retired three years earlier. A majority saw that, lacking an attorney, they didn’t have a will or guardianship arrangements for their children. Parents of children with food allergies identified people whose help they needed to protect their child’s health when parents were not around. One business-owning mom showed her map to her husband and said, “Here’s what I’m doing. How about if you take care of my car?” Another woman enlarged her map and hung it on her bathroom wall to contemplate as she soaked in the tub. Within six months, she tripled the footprint of her retail business, negotiated a better rent with her landlord, and started a foundation to help women with breast cancer. One couple decided against joining three other families to create a time-shared mountain cabin when mapping showed them the workload involved.

Much to my surprise, people found ways to use this in their work, too. That took me back to healthcare to expand on patient journey research and to identify the most trusted COVID-19 vaccine messengers for different population segments. It created a new way to describe the burden of an illness and, therefore, the value of therapy. A luxury brand retailer used it to create a new sales training program. It showed first-generation college students where to build the connections they needed for their future. Several people demonstrated their value to prospective employers by mapping their career connections. I’m happy to report that they left interviews with jobs in hand because they were able to demonstrate the value of their relationships, which is typically a hard thing to commoditize.

Then, seniors read the book, and some changed their retirement plans because of it. They wanted insights tailored to their stage of life. Curious about that, I added them to my research and have followed some for five years. That will be the subject of my next book, Longevity Pioneering: Building Networks to Remain in Control of Your Life. I have proof of concept that building robust networks helps, and I want to show more people how to do that.

People also reinterpreted life experiences through this new lens and had helpful “aha” moments—me included—and it’s yet another example of how “blind” we can be to realities before our eyes. In my case, I saw that the biggest setbacks in my career came from being a homeowner. Here’s why. When you buy a home, everybody talks about the money and whether you can afford the down-payment, the mortgage, and the new roof you’ll need in five years. Nobody asks if you have the bandwidth to manage 20 people. For example, for internal maintenance alone, you will, at some point, need a plumber, electrician, painter/wallpaper installer, HVAC technician, appliance repair technician, chimney sweep and firewood supplier if you have a fireplace, carpet cleaner, heating oil company, dryer vent cleaner, and exterminator for indoor pests (e.g., ants, roaches). For external maintenance, add a roofer, shrub/tree trimmer, grass cutter, window washier, gutter cleaner, snow remover, driveway sealer, mason (for some exteriors), exterminator for outdoor pests (e.g., bats, squirrels), and trash company (in some places). If you ever renovate, which I did, add 10.

No employer would ever expect someone to have 20 or 30 direct reports, but that’s what it takes to own a home. Only in retrospect did I see the connection load home ownership requires. How I wish I could reclaim that energy for my career and social life. Lacking a framework for understanding connections and networks, I missed meaningful data because I couldn’t “see” it.

I’m not unusual, as I’ve learned in my longitudinal research. We take on adulting a little bit at a time, squeezing more into each day until we hit a crisis or burnout. It’s like that metaphor about cooking a frog: if a frog is placed in boiling water, it will jump out, but if it is placed in tepid water that is gradually heated, it will not notice the temperature increase until it is too late and boil to death. That means it’s rarely a question of “whether” but “when” we’ll get cooked. I’m pleased to say that when that happens, people who map their networks do not wrongly blame their bosses, their jobs, or their marriages. Mapping allows them to see life in a new way so they can identify and resolve the real drivers of being overwhelmed. I’d be happier when we all do it proactively, though, and avoid burnout.

Zoë: Do you have any parting words of advice for our readers, who I’m sure are now thinking about their own networks and how to examine or leverage them better?

Glenna: I’ll come back to my goal of keeping talented people in the workforce and say, I’m concerned about women. They carry network workloads for others at work and outside of it, especially if they have kids, kids with special needs or talents, or are caregivers. This is why I’m impatient with typical work-life balance discussions. It’s hard to balance when we’re all blind to the nature and scope of the network connection dynamics, and we’ve blown past Dunbar’s 150 number long ago. In the movie I Don’t Know How She Does It, Sarah Jessica Parker stars as a married woman with two kids and a job that requires travel. She is so overwhelmed managing the 35 connections shown in the film that she quits work. Based on my research, a woman with those demographic characteristics connects with not 35 but 350 people. I don’t know how they do it. I want this work to help them.

The single best thing anyone can do is become aware of their connections. Even that first Awareness step is psychoactive. As someone said, “You liberated me. You gave me data, and now that I have it, I know what to do.” It’s easier to develop that awareness now than it was for me 15 years ago because there’s a network framework to help. In summary, it’ll help readers in four ways:

- They will see they have far more support than they realize. Valuable assets they can use to improve their personal and work lives are hiding in plain sight.

- They will see any mismatch between how they spend their resources and their personal and professional life goals. Most people see that some connections don’t serve them well, even when they’re paying customers. So, they find alternatives.

- They will identify gaps they need to fill with important but missing connections, like attorneys and backup babysitters.

- Lastly, they will have new insights into the lives of others, including their employees and customers. If they bring this awareness into their work, they will find new product and service ideas to satisfy customers. If they’re market researchers, they will find valuable new insights for clients.

Zoë: Thank you so much for sharing your journey with us, Glenna. I hope this article inspires readers to explore their networks and use this new knowledge to improve their

personal and professional lives.

REFERENCES

(1) Footnote for gorilla x-ray study: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/

articles/PMC3964612, Trafton Drew, Melissa L. H. Vo, and Jeremy M. Wolfe, “The invisible gorilla strikes again: Sustained inattentional blindness in expert observers,” Psychol Sci. 2013 Sep; 24(9): 1848–1853.

(2) Robin Dunbar’s 150 connections: Dunbar, Robin.

How Many Friends Does One Person Need: Dunbar’s Number and Other Evolutionary Quirks. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010.

(3) Christakis has a TED Talk, which is the most easily accessible way to see the basic premise of his research: www.ted.com/talks/nicholas_christakis_the_hidden_influence_of_social_networks?

subtitle=en. He also has a variety of publications on the topic:

- Christakis, NA; Allison, PD (2006). “Mortality after the Hospitalization of a Spouse” (PDF). New England Journal of Medicine. 354 (7): 719–730.

- Christakis, NA; Fowler, JH (2007). “The Spread of Obesity in a Large Social Network Over 32 Years” (PDF). New England Journal of Medicine. 357 (4): 370–379.

- Christakis, NA; Fowler, JH (2008). “Quitting in Droves: Collective Dynamics of Smoking Behavior in a Large Social Network” (PDF). New England Journal of Medicine. 358 (21): 2249–2258.

- Fowler, JH; Christakis, NA (2009). “The Dynamic Spread of Happiness in a Large Social Network” (PDF). British Medical Journal. 337 (768): a2338.

- Fowler, JH; Christakis, NA (2010). “Cooperative Behavior Cascades in Human Social Networks.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107 (12): 5334–8.

- Rand, DG; Arbesman, S; Christakis, NA (2011). “Dynamic Social Networks Promote Cooperation in Experiments with Humans.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108 (48): 19193–8.

- Apicella, CL; Marlowe, FW; Fowler, JH; Christakis, NA (2012). “Social Networks and Cooperation in Hunter-Gatherers” (PDF). Nature. 481 (7382): 497–501.