By Dr. Dave Oventhal, Subaru of New England, Professor of Automotive Strategy, Director, CAMS Research Institute Northwood University Midlands, Michigan, oventhad@northwood.edu

Are you frustrated when only product planners or product managers attend your qualitative research? Have you tried multiple tactics to convince design and engineering teams to attend field studies, but no one shows up—or worse, insights are ignored? If you run into these problems, especially when developing physical products, accelerated product development (APD) is a great way to convince the naysayers and the disengaged.

INTRODUCTION

Qualitative researchers within the physical development world often struggle to convince design and engineering teams to join “field trips.” These teams often have ready-to-use excuses to avoid research trips (e.g., no time, already know what users want). Avoiding fieldwork and ignoring insights creates various problems when developing physical products:

- Late specification changes

- Costly rework

- Products misaligned with user needs

- Missed business targets

Unfortunately, researchers and product planners are often their own worst enemies. During the front end of the development process, research and planning teams typically conduct lengthy qualitative research, casting a wide net on the area of investigation and following up with extensive quantitative studies. Before long, several months have elapsed without any hard decisions being made, frustrating design and engineering teams. These teams want to start running and view research as slowing things down or confirming (what they think) they already know.

Unfortunately, researchers and product planners are often their own worst enemies. During the front end of the development process, research and planning teams typically conduct lengthy qualitative research, casting a wide net on the area of investigation and following up with extensive quantitative studies. Before long, several months have elapsed without any hard decisions being made, frustrating design and engineering teams. These teams want to start running and view research as slowing things down or confirming (what they think) they already know.

During this lengthy up-front research phase, design and engineering teams are not standing still. Detailed sketches are developed, and engineering problems are “solved.” Unfortunately, these early efforts typically result in late-stage changes and costly rework after research insights reveal flaws in the team’s decisions. APD is a great framework to avoid these problems.

WHAT IS APD?

The APD process focuses on creating a team of research advocates who are engaged in all aspects of research: planning, execution, analysis, and reporting. APD consists of:

research: planning, execution, analysis, and reporting. APD consists of:

- Delaying decisions until the last possible moment.

- Conducting a series of iterative cycles (i.e., sprints) to address knowledge gaps (i.e., what is not known) and validating hypotheses.

- Creating physical artifacts and visually communicating learnings to stakeholders.

- Documenting learnings for current and future projects.

Using concepts from agile product development (i.e., sprints, retrospectives) and lean product development (i.e., engaging with users, capturing and storing knowledge), APD typically uses qualitative research to quickly address key development questions and ensure product development teams make the best decisions in the shortest time. APD is especially valuable for physical product development, which involves a multitude of dependencies (e.g., engineering and design drawings, durability testing, system calibration) and a lack of flexibility due to long lead-time items (e.g., tooling, material sourcing, production scheduling). By removing the fuzziness from and shortening the front-end of development, APD helps to:

- Reduce late changes and costly rework (and prevent associated delays)

- Create improved product requirements based on user insights

- Accelerate time-to-revenue (i.e., sales)

THE APD PROCESS

After a development project has been approved, cross-functional teams meet and conduct the following two steps:

- Knowledge gaps (i.e., the key unknowns) are identified. These unknowns are then prioritized based on the timing of when each will negatively impact associated dependencies.

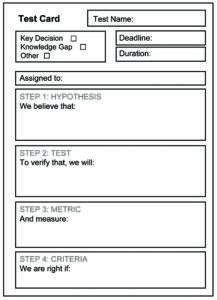

- Hypotheses and expected outcomes are developed for the prioritized unknowns. The Test Card from Strategyzer (shown above left) is a great tool for teasing these out and recording them due to its simple, one-page layout and short descriptions/explanations (www.strategyzer.com/library/the-test-card).

Once the main unknowns are prioritized and hypotheses developed, the following six steps occur:

Once the main unknowns are prioritized and hypotheses developed, the following six steps occur:

- Sprints are planned and executed. These short, time-boxed cycles (typically two to four weeks) are used to address the team’s knowledge gaps. Sprints force everyone out of the studio, lab, and office to engage with users directly. The preferred methodology is in-depth interviews (IDIs), which allow for direct interactions with users. Typically, 10 interviews or fewer are sufficient to uncover similar patterns. Quantitative research may be statistically accurate, but it misses nuances and valuable learnings that only come from first-hand interactions with users.

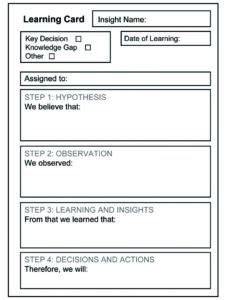

- Learnings are documented and reviewed. One great template to use in this step is the Learning Card from Strategyzer (shown above right) due to its simple, one-page layout and short descriptions/explanations (www.strategyzer.com/library/the-learning-card).

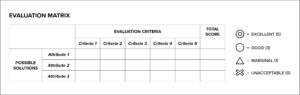

- Solutions are ideated, and an ideal solution is chosen. Using an Evaluation Matrix (see example above) to identify the alternative solutions and record the logic behind the final decision creates an excellent resource to explain how and why the final decision was reached.

- Physical artifacts are created (e.g., videos, 3D components, storyboards). Artifacts detail the learnings from the sprint and visually communicate the final decision. These artifacts help align team members and act as engaging “props” during gate reviews and other key meetings.

- Retrospectives are conducted after each sprint. These regular, planned meetings identify what went well, what needs to be improved, and what the team learned.

- Learnings are stored in a central repository and shared. These learnings should be considered high-value corporate assets that can assist current and future projects.

CHALLENGES OF APD

APD’s main challenges typically involve convincing design and engineering teams to participate in qualitative research, utilize market and user insights, and delay decision-making until after the research is complete. Here are several strategies to encourage buy-in for the APD process and convince teams to participate:

- Engage stakeholders early with nemawashi, or “building consensus using one-on-one discussions.” Used within many Japanese organizations, nemawashi is a premeeting that allows information-sharing and gathering of key stakeholder feedback before formal meetings (e.g., Stage Gate reviews). It takes place in a relaxed, informal setting (typically over coffee or lunch) and ensures everyone is included in the research process, avoiding surprises when the team gets together at gate reviews or other key development stages. A member of the research team should schedule, conduct, and document these informal meetings to ensure team member feedback is included in the research.

- Enlist product planners, program managers, and product managers to help “herd the cats.” These individuals define product requirements, schedule and maintain development timing, and are responsible for achieving business targets. They can convince teams to attend regular meetings, especially at the beginning of conceptualization. They can also foster early collaboration to identify and prioritize the key unknowns and assist with research planning, creating group ownership of the process.

- Recruit design and engineering advocates. Find advocates within the design and engineering teams to help convince co-workers. Engaging design and engineering teams in all stages of the research—planning, execution, analysis, and reporting—will ensure the research is “everyone’s,” not just the research team’s priority. As most pushback to early research comes from the design and engineering teams, recruiting advocates from these teams early in the process helps to ensure everyone’s voice is included in planning.

- Convince sales and marketing leaders that APD will help differentiate product offerings through improved product requirements, while also getting products to market faster.

- Provide examples of past projects where APD resulted in projects launching early, requiring minimal rework or late changes, or exceeding customer expectations. It is also useful to provide examples of projects where APD could have improved decisions and product success. However, do not make issues personal. The goal is to build support for future research. Keep things positive. Know your audience and avoid any negative examples if they “might ruffle any feathers.”

BENEFITS OF APD

- Creating a development team built on trust, cooperation, and collaboration; in effect, removing silos.

- Delaying decisions until the proper information has been collected.

- Avoiding schedule delays due to late changes or costly rework.

- Developing products based on user needs and wants instead of guesses and assumptions.

- Strengthening stakeholders’ confidence via demonstrating that decisions were well-thought-out and validated with market insights.

- Documenting learnings for current and future development projects.

CASE STUDY: REAL-WORLD APPLICATION

CASE STUDY: REAL-WORLD APPLICATION

A motorcycle development team was tasked with developing a scrambler-style motorcycle (a street motorcycle modified to ride off-road) primarily for sale in Indonesia. Historically, scramblers used high-mount exhaust systems to avoid damaging the exhaust on rocks, tree stumps, and other obstacles. Though used on scrambler motorcycles since the 1950s, a high-mount exhaust presented several challenges, as it:

- Tends to radiate excessive heat on the rider’s and passenger’s legs

- Creates a wide bike, resulting in an uncomfortable riding position

- Is not ideal in countries where passengers are on motorcycles daily

- Does not allow the fitment of dual saddlebags

The team wanted to use a low-mount exhaust system but were concerned customers would not accept it on a scrambler. Thus, the project’s biggest unknown was quickly identified and prioritized: Would a scrambler with a low-exhaust system sell? After all, the exhaust position would impact the overall design of the motorcycle, as well as key engineering areas such as heat management, engine performance, and several other interrelated facets. Exhaust position would also impact accessory development.

Considering these multiple interrelated dependencies, the team wanted to confirm this unknown immediately. They agreed to try APD to answer this big unknown, as guessing was too risky. After two weeks of planning and one week in the field, the team uncovered the following insights:

Considering these multiple interrelated dependencies, the team wanted to confirm this unknown immediately. They agreed to try APD to answer this big unknown, as guessing was too risky. After two weeks of planning and one week in the field, the team uncovered the following insights:

- Most scrambler owners never rode beyond smooth dirt roads (think of SUVs: built for off-road driving but most never touch dirt).

- A low-mount exhaust would be acceptable on a scrambler as high ground clearance was not required by most users.

- The low-mount exhaust created a strong design differentiator compared to competitors.

- A high-mount exhaust would not be acceptable in Indonesia, the main selling region, due to the perception of excessive heat on the rider’s and passenger’s legs.

- Scrambler owners required dual saddlebags to carry work and school supplies.

Given the results of their research, the team decided to proceed with a low-mount exhaust. In three weeks, the team not only answered the project’s main unknown, but the design and engineering leads who participated became believers in qualitative research and sprints. They not only learned that a low-mount exhaust would be acceptable but, most importantly, saw firsthand how customers modified their motorcycles, inspiring new ideas for further differentiation. In addition, a mock-up of the proposed exhaust was fabricated to visually communicate the design direction.

Long days traveling and interviewing customers and dealers, eating meals together, and spending valuable time discussing what was learned created a truly cross-functional team. This short, focused sprint resulted in stronger trust and improved communication among the team. In addition, the insights gleaned from direct user engagement convinced the design and engineering leads they needed to talk to customers regularly.

valuable time discussing what was learned created a truly cross-functional team. This short, focused sprint resulted in stronger trust and improved communication among the team. In addition, the insights gleaned from direct user engagement convinced the design and engineering leads they needed to talk to customers regularly.

After the product launch, the low-mount exhaust scrambler was a market success. It exceeded sales targets, created a new segment within the Indonesian motorcycle industry, and captured several design awards. Customers loved the tough off-road styling, and passengers enjoyed the comfortable riding position. The motorcycle was quickly offered in several other Southeast Asian markets with similar success.

CONCLUSION

APD is an excellent process to ensure physical product decisions are based on market and user insights, not guesses or assumptions. Combining the benefits of agile research and lean research and incorporating physical artifacts, APD is an excellent way to engage design and engineering teams in qualitative research. Ensuring design and engineering teams absorb lessons and observations firsthand, rather than solely via a research team, APD disciplines teams to delay decisions until the last possible moment when the proper amount of information is gathered.

The APD process reminds teams that research is not “your research”; it is “everyone’s research.” Research is about what the study reveals and what the results communicate about how products can be improved. The process also reminds naysayers and other disengaged stakeholders that the goal is for improved products and customer experiences. The ability to bring the customer’s voice into the development process earlier ensures the design is based on evidence, not just opinions.

A great analogy is asking for directions, which might take a few minutes but could save hours in the long run.

Direct interaction with users is a great way to convert naysayers into believers, remove silos, and create a true cross- functional development team. Reducing the possibility of late changes and costly rework ensures faster time-to- revenue and increases stakeholder confidence in the benefits of market and user insights. For teams that tend to avoid participating in and utilizing qualitative research, APD can quickly make the unknowns known, and create a team of believers.

REFERENCES

Alvarez, Cindy. Lean Customer Development: Building Products Your Customers Will Buy. O’Reilly, 2014.

Gothelf, Jeff, Josh Seiden, and Jeff Hoyt. Lean UX: Designing Great Products with Agile Teams. O’Reilly, 2019.

Knapp, Jake, John Zeratsky, Braden Kowitz, and Dan Bittner. Sprint: How to Solve Big Problems and Test New Ideas in just Five Days. Simon & Schuster, 2016.

Radeka, Katherine, and Kathy Iberle. When Agile Gets Physical: How to Use Agile Principles to Accelerate Hardware Development. Chesapeake Research Press, 2022.

Radeka, Katherine. High Velocity Innovation: How to Get Your Best Ideas to Market Faster. Career Press, 2019.

Radeka, Katherine. The Shortest Distance between You and Your New Product: How Innovators Use Rapid Learning Cycles to Get Their Best Ideas to Market Faster. 2nd ed. Chesapeake Research Press, 2017.

Sharon, Tomer. It’s Our Research: Getting Stakeholder Buy-in for User Experience Research Projects. Morgan Kaufmann, 2012.