By Darren Harvey, Principal, Lotus Research, Milton Keynes, UK, darren@lotusresearch.co.uk

Imagine the perfect focus group or IDI.

We welcome the participants, warm them up with some gentle personal questions, and then dive into the discussion guide. We ask our questions clearly, the participants understand just what we mean, and the responses flow back—open, truthful, and revealing. Then we raise a few thorny topics, but the participants feel so comfortable that they share their private thoughts freely. The discussion is over, we have the data we need, the participants say how much they enjoyed the session, and the clients are delighted.

If only it were so straightforward. More often than we care to admit, we find ourselves wading through treacle—the participants can’t seem to relax, our questions and interpretations don’t quite land, the responses are laden with intellectualization or deviation, and we sense dodging—an unwillingness to engage with the topic or to be fully present in the space. Not only do they seem to be concealing something from us, but they might even be hiding their true feelings or opinions from themselves.

What do we do in these situations? Typically, we try our hardest to be warm, open, and empathetic—in the hope that this will soothe our participants into feeling comfortable enough to share their true selves with us. This approach is drawn from the person-centered psychotherapy pioneered by Carl Rogers in the 1960s. Indeed, there are many similarities between a psychotherapy session and a qualitative research discussion—both are trying to uncover some kind of truth, both are encounters between people with no other connection to each other, and both have the potential to hide the reality behind defensive behaviors.

The Core Principles of Person-Centered versus Psychodynamic Therapy

Rogers taught that the way to establish a genuine and honest relationship in therapy was to focus on three core principles—empathy, unconditional positive regard, and congruence (which we might describe as a natural, authentic manner on the part of the therapist or, in our case, the researcher). Of course, this person-centered approach is extremely valuable in putting participants at ease and creating the potential for open, honest sharing. But still, no matter how diligently we employ this approach, we can still sense participants dodging or straying from the subject.

After 20 years in qualitative research, I recently completed a three-year diploma in psychodynamic counseling, a modality that offers once-weekly therapy to adults, using psychoanalytic theory and techniques based upon the theories of Freud and his followers. The comparison with the Rogerian approach is startling—when we sense that our patients are becoming more defensive, we take the opposite approach to the person-centered one. Instead of softening our tone, choosing soothing words, and rephrasing our questions to sound gentler and kinder, we lean into the defensive behavior by drawing attention to it, validating it, and then gently challenging it.

It would be useful here to look at the function of these defensive behaviors—why, when confronted with uncomfortable questions (or questions asked in unfamiliar settings), do humans do things like intellectualizing, laughing things off, projecting their own traits onto others, changing the subject, focusing on small talk, or zoning out? Freud believed that the fundamental reason for this kind of defensive behavior was to avoid psychic pain and later focused on the increased anxiety that emerges when we are forced to consider things that make us feel uncomfortable—whether this is a sense of discomfort at our own hidden desires, our worries about hurting or upsetting others, our need to be seen as socially acceptable, our feelings of inadequacy, our deepest fears, or thoughts or experiences that remind us of past traumas.

Tackling Defenses in Qualitative Interviewing

In qualitative research interviews, just as in therapy, we often sense these anxieties and the defensive behaviors they cause—and so often, they act as a barrier to truth and understanding.

But isn’t there a risk associated with calling out and challenging these delicate structures when we work with participants? Working through these kinds of defenses in therapy can take months or even years—many of these defenses were laid down in childhood and act as long-term strategies that enable humans to function among the stresses and strains of the adult world. How can we be expected to tackle them during a single encounter with a participant or group? Would it not be unethical to start dismantling a participant’s coping strategies and then send them back out into the world?

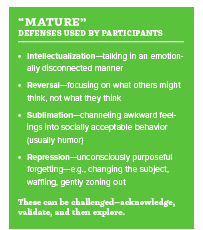

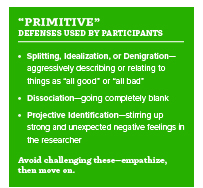

The key here is to learn to distinguish between what we call mature defenses and primitive defenses. To help us, we can turn to the work of Anna Freud, Sigmund’s daughter, who named and explored the key defensive strategies and behaviors used by humans and categorized them into mature defenses—grown-up, psychologically healthy ways to navigate a complex and demanding world; and primitive defenses—more child-like and internalized behaviors that protect us from fears and dangers that were laid down in early life. Essentially, it is the mature defenses that we can challenge and explore in qualitative research interviews and the primitive defenses that we should leave well alone for ethical reasons, as well as practical ones.

To do this, we need to be able to recognize the defenses being employed by our participants and to be clear about which category they belong to. Let’s start with an overview of the mature defenses.

An Overview of Mature Defenses

Intellectualization: Fundamentally, this involves talking about feelings in an emotionally disconnected manner. In qualitative research, this manifests when participants offer a rational overview of a potentially meaningful topic—we will all be familiar with this! But all too often, we’re not sure where this is coming from: Is the participant particularly left-brained? Are they uncomfortable with sentimentality? Does the topic genuinely have no emotional resonance for them? We will only find out if we gently challenge the defense. We might say something like, “We’re getting a bit think-y here, I wonder what that’s about…” or “Perhaps this brings up some feelings as well…”

Reversal: This is where the speaker switches their position from subject to object, or vice versa. I see this most commonly when asking for opinions on a new idea, only for the participants to tell me what another type of person (older, younger, male, female, etc.) would think of it. Before my therapy training, I used to say, “Well, we’re going to be talking to that group tomorrow, but I’d like to know what you think”—but I recently realized that this approach fails to acknowledge or validate the defense. I’m now saying things like, “We’re thinking about other groups of people here; perhaps it’s harder to connect with this as yourself…”

Sublimation: Freud believed that one of the healthiest mature defenses was sublimation—taking a socially unacceptable impulse and transforming it into a creative form of expression such as art, sport, or humor. In qualitative, especially in groups (and especially in the UK), we see a lot of humor being used, often as a social lubricant but also as a way to avoid exposing something potentially thorny such as lust, envy, greed, or any of the other so-called deadly sins. Again, we can observe, validate, and explore by saying something like, “There’s something quite funny about this. I see it, but I wonder if we could think about what’s underneath that…”

Repression: We can characterize this as an unconsciously purposeful forgetting—where we push something out of our minds because it makes us anxious to think about it. In research, this is most apparent when participants change the subject, waffle, gently zone out, or (in groups) agree with what everyone else says. Of the mature defenses, this can be the hardest to challenge because the participant is often giving us so little material to work with. But that’s not to say we should ignore what’s happening—again, acknowledge, validate, and explore. How about asking, “It seems a bit difficult for us to get into this subject… maybe we could think about what’s happening here…”?

By leaning into the participant’s discomfort, we validate their feelings and allow reality to come to light. Through gentle challenging, we are showing them that it’s OK to feel a little uncomfortable or anxious with the topic we are exploring or with the feelings that it brings up. In addressing these defenses, try not to ask too many questions (direct or indirect) but instead embrace a spirit of collaborative curiosity—phrases like “perhaps” and “I wonder” are very useful here. In therapy, we talk about finding truths together—we are not subjects and objects, but partners in helping to create understanding. Where possible, try to use “we” rather than “I” or “you”—this can create a reassuring sense of a shared and supportive mission. In my recent qualitative work, I have found that participants really value being seen for who they are and being given the chance to explore and understand their own anxieties.

But how do we sense whether the defensive behaviors shown by participants are mature ones or more primitive ones? Essentially, we can tell by being fully present in the space and listening to our instincts. Do we sense the participant gently dodging the topic? Does the participant still feel real and present in the space with us? Do we get the sense that they are still prepared to contribute? Do the feelings in the space between us still make a kind of emotional sense? In this case, we are probably dealing with mature defenses, which can be safely explored.

But how do we sense whether the defensive behaviors shown by participants are mature ones or more primitive ones? Essentially, we can tell by being fully present in the space and listening to our instincts. Do we sense the participant gently dodging the topic? Does the participant still feel real and present in the space with us? Do we get the sense that they are still prepared to contribute? Do the feelings in the space between us still make a kind of emotional sense? In this case, we are probably dealing with mature defenses, which can be safely explored.

If, however, we sense a hard emotional resistance, we are probably encountering primitive defenses. We notice these in a variety of ways—for example, when we feel that the participant is not emotionally present, their behavior seems strange and unsettling to us, they give the impression of wanting the discussion to be over, or we ourselves feel confused or angry or irritated for no apparent reason. Something in the topic or in the interaction between us has triggered age-old fears and deeply-felt anxieties. In these situations, we might benefit more from the Rogerian approach of deepening our empathic and positive attitude and moving gently onto a less troubling topic.

An Overview of Primitive Defenses

Here are some of the primitive defenses that we can look out for:

Splitting, Idealization, or Denigration: This is where things are excessively praised or criticized with no sense of a grey area in between. The object of the praise or criticism could be the topic, a brand, an idea, or even the researcher. Suddenly, everything being discussed becomes incredible or awful, to a degree that seems to not quite make emotional sense. What has Concept J2 done to make this person so incredibly angry? Why does Brand A always do everything perfectly, and why is Brand B the worst in the world? Why is the participant acting like they want to be my best friend? More often than not, the anger or reverence in these situations comes from another place—it might be a manifestation of internal psychic states, a traumatic experience in the past, or even a deep-seated, black-and-white way of seeing the world. Our job here is to show that we have listened and to move on—there is little to be gained by digging deeper into such polarized feelings, and calling out the defense may be psychologically harmful to the participant.

Dissociation: This occurs when a participant appears to completely zone out of the discussion, and we sense ourselves being shut out. I see this more often in groups—perhaps as a result of extreme discomfort with an aspect of the discussion, but just as likely due to acute social anxiety (or even having had a really, really bad day). No matter how hard we try, we find it very difficult to draw them back into the discussion. When this happens, we perhaps need to accept our own lack of control over the behavior of others—it may be that their capacity to participate has become extremely limited, and it won’t benefit anyone to push through that.

Dissociation: This occurs when a participant appears to completely zone out of the discussion, and we sense ourselves being shut out. I see this more often in groups—perhaps as a result of extreme discomfort with an aspect of the discussion, but just as likely due to acute social anxiety (or even having had a really, really bad day). No matter how hard we try, we find it very difficult to draw them back into the discussion. When this happens, we perhaps need to accept our own lack of control over the behavior of others—it may be that their capacity to participate has become extremely limited, and it won’t benefit anyone to push through that.

Projective Identification: This is perhaps one of the strangest phenomena in psychoanalytic theory. It occurs when a therapist (or interviewer) starts to feel unexpected and extreme negative emotions in themselves, such as anger, despair, fear, or “frozenness” of the mind or body. This can occur when a patient (or participant) is carrying an emotion very strongly but cannot admit it into their conscious mind. As a result, the therapist or interviewer, particularly a highly empathetic one, starts to pick up on the emotion subconsciously and feels it keenly themself. So, if you start to experience strong and unexpected negative feelings in your research discussions, use them to hypothesize what feelings the participant may be experiencing unconsciously, but save any further thought or discussion about this for the analysis stage.

Conclusion

We all bring our own psychological defenses to every interaction that we experience, and in most cases, they are functional ways to navigate the pressures of our lives. However, they can cause an unconscious distortion of thought and perception that can hamper our ability to dig deep and make the most of our qualitative interviews. Provided we can safely identify defensive behaviors as mature and healthy, we don’t need to ignore or gloss over them. By acknowledging, validating, and exploring defenses, we have the capacity to understand our participants better, offer them a more authentic and valuable interaction, and provide our clients with deeper and more meaningful insights.