by Zoë Billington, User Research & Customer Insights, Santa Monica, California, zbillington@gmail.com

by Zoë Billington, User Research & Customer Insights, Santa Monica, California, zbillington@gmail.com

Interview with Rachel Lawes, PhD, Lawes Consulting Ltd.

Zoë: As we always begin with Luminaries, let’s start with the 10,000-foot view of your career. What are some of the experiences that have led you to where you are today?

Rachel: Well, I’m from a very ordinary working-class family in the U.K. My parents didn’t have a lot of money—but a guiding principle was that no matter how little money there was in the household budget, there was money for books. I’m so grateful to my mother for doing that.

I went to university and received a degree in psychology a bit later than other people. I was 27 and already a parent. I was talent-spotted early in my degree and told to work hard. I did what I was told, and I went ahead and did a PhD in social psychology.

I was supervised by Jonathan Potter, now Dean of the School of Communication and Information at Rutgers University in New Jersey. He more or less invented the type of discourse analysis that revolutionized social psychology in the 1990s, also known as discursive psychology.

Zoë: For those of us who are unfamiliar with discourse analysis, can we do a quick sidebar and explain what that means?

Rachel: Discourse analysis reveals the mechanisms hidden inside everyday speech and conversation. The way a discourse analyst would describe it is that it’s like taking the back off the toaster to see how it works. Or, to use a word borrowed from commercial semiotics, we could say that it “decodes” everyday conversation.

What I learned as a discourse analyst is that if you look at people talking to each other like we’re doing right now, what you observe is that only about 50 percent of the conversation is concerned with the topic, while the other 50 percent is about the conversation itself. We’ve done a lot of this more “meta” type of talk today: in the first few minutes of this conversation, we said things like, “Let’s talk about this first,” and “We’ve got about 40 minutes to do such and such.” We exchanged a few jokes between us. We had a moment of self-deprecating humor over whether or not I’m actually a luminary. You asked me to give a 10,000-foot view of my career to keep the conversation within certain limits. So, in any conversation, about 50 percent of what’s said is like that, and it’s very revealing. You can see people shaping reality together, just like you and I are doing right now.

Zoë: Thanks for that—okay, now, back to your time studying under Jonathan Potter.

Rachel: So, I was one of his first PhD students and did my doctoral research with him, which was incredible. It changed my life. I quickly discovered as I was looking at the “family tree” of discourse analysis, which was a relatively new thing, that it had influences from various places: sociology, anthropology, and semiotics.

As I explained, discourse analysis is kind of like a precision tool for understanding language, communication, and spoken interaction. But what I discovered about semiotics was its enormous scope. In semiotics, we’re interested in all forms of human communication—and we mean all of them: music, mathematics, architecture, fashion, retail environments, you name it. I was almost drunk on the scope of the thing.

So instead of just conversational mechanics, we’re talking about the entire scope of human communications: what people wear, what they’ve done to decorate their offices, and I don’t know how much longer it’s going to last, but you know those big, massive eyebrows that people have? That is semiotics right there—it’s a form of communication. The reason why marketers like semiotics is because it includes visual signs and symbols, which are useful for designing advertising, packaging, retail displays, and more.

Zoë: So, you’re drunk on semiotics… what happened next?

Rachel: I probably would have had an academic career, but I needed to make some money after a certain point because I’d been broke my whole life. So, I finished my PhD, and I came to work in the market research industry in London at the turn of the century. I worked for a small market research agency for two years. At the time, I was a bit surprised that the types of research methods were really limited: surveys, in-depth interviews, focus groups, a tiny bit of ethnography, and almost no semiotics. It was a disappointing situation, especially after I had knocked myself out learning about research methods for all those years. I wanted to add to the repertoire, and I figured that semiotics might be a good place to start. So, I wrote a conference paper called “Demystifying Semiotics,” which was an attempt to answer some questions about the method in a straightforward way. I used a few popular brands from banking and food as a way of demonstrating the principles. I presented it at a conference of the Market Research Society in the U.K. and then subsequently published it. It went viral, which was a weird feeling because I only had two years of commercial experience at that time. Because of its success, I started my own company, which is celebrating its 21st anniversary this year. Over that time, I’ve served a lot of brand-owning clients around the world. I continued to publish a lot of conference papers, and I started to deliver training and teaching in academic and professional settings. In 2020, I published my first book, and then I published a second one in 2022, which just won an award for the Best Book in the Sales and Marketing category at the Business Book Awards 2023.

So that is the whole story of my life.

Zoë: Wow! I have many follow-up questions, but let’s start with one that will hit close to home for our readers. How would you say that semiotics overlaps and/or differs from other research methods that our readers might be using?

Rachel: They work really well together. But what are the differences if we want to find them? The difference is between the “inside out” model of research and the “outside in” model.

Market research is roughly about 100 years old, right? Throughout almost all this history, it took an “inside out” approach. Remember me saying that when I first started out, we really only had surveys, in-depth interviews, and focus groups, and that was it, right? So, all of these methods, which are fantastic methods, are borrowed from—guess what?—psychology. They’re just tools, and we borrowed those tools from the discipline of psychology.

Psychology is a big discipline, but most of it is the study of individuals and what goes on inside their heads. That comes with various assumptions, for example, that individuals are all different from each other, and that everybody has a lot of interesting but secret and hidden stuff going on in their heads, like attitudes, beliefs, preferences, motivations, prejudices, tastes, and all that. So, the job of the market researcher is to use psychological tools—like a carefully crafted survey questionnaire or an interview discussion guide with some projective techniques—designed to get the secret stuff like attitudes, beliefs, and perceptions out of people’s heads and make them visible to the world. That became known as the “inside out” model of research, where the stuff begins inside the head, and we want to get it out.

Later, a complementary model emerged in market research—rather belatedly because it had been going on in academia for a long time. This new family of research methods is where we locate ethnography—which is a form of participant observation where you try to step into somebody else’s life and live it as a real thing—and semiotics and discourse analysis. These take a contrasting “outside in” approach where we’re not trying to get stuff out of people’s heads. We’re instead asking how it got there in the first place. Where did all these attitudes, beliefs, motivations, and perceptions come from? The answer is usually presumed to be that they come from the surrounding culture, of which each person has no choice but to be a part. There’s no escape from the supermarket, as I’m quite fond of saying—every single one of us is a prisoner of our own culture, and to a lesser extent of global culture as well, especially since the internet arrived. So, this set of methods, when done right, is not about interrogating people about their opinions of Brand X. It’s about asking: what kind of society needed Brand X to exist?

Zoë: That’s a really helpful distinction. Can you share an example of semiotics and qualitative together in action?

Rachel: This classic case study, which won some awards in 2011, is in my book. It concerns a Swedish company called Essity, which makes household products like toilet paper. When I started to work with them, they were really excited because they managed to buy the European license for Charmin toilet paper, one of the world’s most loved brands. But Procter & Gamble attached all these conditions to the sale. They said you can have it, but within three years, you’ve got to lose all the brand assets that make the brand recognizable. You can’t call it Charmin, can’t have the Charmin bear, and can’t talk about proprietary technology. The situation was really kind of draconian.

The question Essity called me with was how to make a brand look and feel as lovable in just the same way as Charmin while dropping everything that makes it Charmin. That’s when we got semiotics involved. When you’ve got a creative problem, you can’t expect consumers to come up with ideas for you in the first place, but semiotics is great at doing that.

I’ll share two things to summarize what we did. First challenge was: what are we going to do about the Charmin bear? It’s a semiotic sign. In the wild, bears are quite fierce, but if you look at the way that they’re represented in popular culture, they’re a bit more like Homer Simpson. Think of Paddington Bear or Winnie the Pooh—they’re good-natured, dopey, kind of stupid, and they’ve got big bottoms and small heads. So, I said to the marketing director: we need an animal like that because it’s nonthreatening and cuddly. Honestly, consumers are often anxious about poo, which is what we’re talking about when we’re talking about toilet paper, right? So that’s why people like toilet paper mascots to be animals that are similar to bears. It’s not just that bears are cuddly, but we also all know what bears do in the woods! So, we came up with koalas. They’re bad-tempered and smelly in reality, but in the popular imagination, they’re cuddly and babyish and lovely. We showed our koala to some consumers in a focus-group setting, and they said it’s adorable, and that they loved it.

Next, you might be wondering what happened to the name. We looked at what was going on with the name and said that one of the most important things about it is that soft sound at the beginning. The soft CH seems a little bit French, which makes it quite feminine and delicate. We said you want something that has this soft, feminine, squishy-squashy kind of sound. So, we generated a few names for them, and the team liked “Cushelle” the best. We went back and showed the name to consumers, and they loved it.

When Essity did the rebrand—with the cuddly koala marsupial and the slightly French-sounding soft “Cushelle”—sales started to go up. This was quite the opposite of what Essity had been told to expect at the outset of making radical changes to a much-loved brand. Essity was expecting a big loss, and instead, they made a profit thanks to semiotics.

Zoë: What an amazing case study. You’ve applied your expertise to consulting, writing/publishing, and teaching. Is the way you define and/or practice semiotics different in these three spheres?

Rachel: That’s a great question; nobody’s ever asked me that before. If we’re going to talk about business consulting, which is where most of my income comes from, then above all, I want to be helpful to my clients. I’ve been doing this for 21 years now commercially, and in that time, I have generated a lot of money for a lot of brand owners. At this point in my career, I focus on essentially two things: what they want to do with their business and what I think is going to make the most money for them. If they want to assemble a team that consists of a neuro marketer, an artificial intelligence (AI) specialist, and a qualitative researcher, and they’re going to do a big survey, and they want some semiotics as well, that sounds great to me, and I’m happy to work with whatever combination of methods and people. My only concern really is how we can make this client’s brand more successful because that’s why they hired me. I’m not going to split hairs over philosophical tensions between different approaches to research.

However, if I’m teaching or writing, I care more about methodological differences, and I’ll use precise language because I want to be helpful in teaching another researcher how to do semiotics. For example, I’ll say, “This is what we mean by this word,” and “This is how it’s different from these other words that you might have heard of.”

It’s not necessary for our clients to speak and think like academics. It’s only necessary for our clients to be good at doing their own job. It’s like when you go and talk to a participant as a qualitative researcher—you know it’s not your job to teach them how to use marketing language. It’s not your job to correct them. Your job is to get in and insert yourself into their reality, their version of reality, so you can understand what’s going on. It’s exactly the same with clients.

So that’s where you’ll find a difference in how I talk about and practice semiotics. If I’m teaching or writing, then I’ll use language in a very precise way because I think that I owe it to the people who are giving me their time to be as specific as possible. With clients, I want to fit into their roles and do all I can to help them achieve their business objectives.

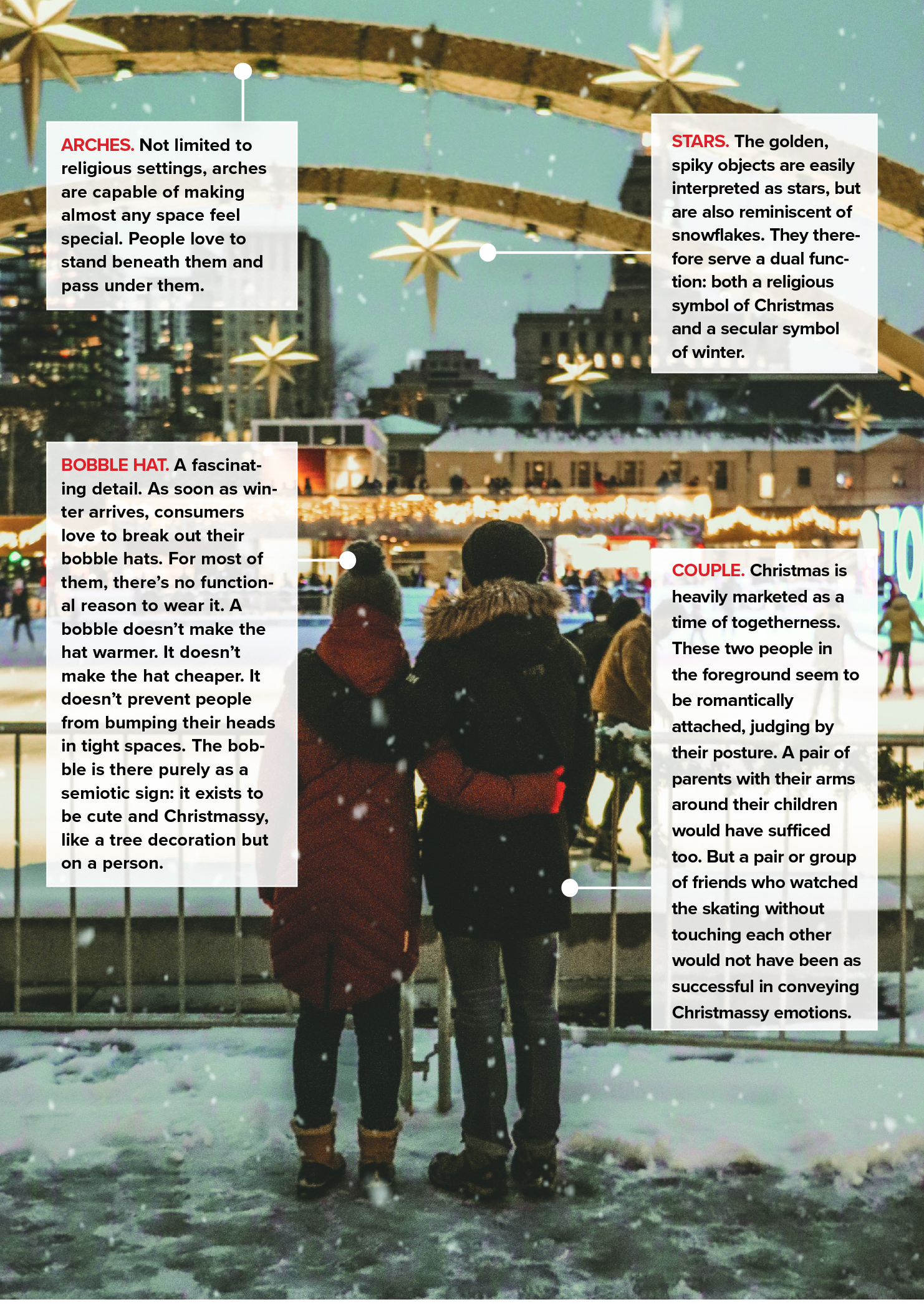

Rachel analyzes a winter scene through the lens of semiotics.

Zoë: On the topic of your books, can you tell us more about the content of them and who you wrote them for?

Rachel: My first book is a teach-yourself course in semiotics. I’d had 20 years of people asking me the same questions, like what is semiotics? What is it useful for? Do you have a case study? Is there a procedure? How do I put this in a proposal? What do I do about sampling? How do you ensure the validity of your insights? This book is a complete “all your questions answered” guide to semiotics—everything you’ll ever need.

My second book is the one that just won the award the other day, and this is really a book for clients about applied semiotics in retail. The first half talks about how to sell things more effectively in stores, whether physical or digital. The second half of the book is about the future.

My initial thought when I was planning the book was that I would write it in two halves. I thought the first half would be about consumers and their view of shopping, and the second half would be about the business point of view. But as I was writing, I came to realize that the two halves were about the present and the future. Consumers pretty much live in the present day. Do you remember what I was saying about “there’s no escape from the supermarket”? Well, because of that, most people are pretty focused on the options they are offered in the present day. Businesses are very focused on the future—constantly trying to predict what comes next and strategizing. Businesses have the ability to shape and control the future in a way that your consumer will rarely have, so the second half of the book is about that. It goes as far ahead into the future as I can see, which is a pretty long way.

Rachel Lawes is the author of two books

Rachel Lawes is the author of two books

Zoë: What do you say to the reader or client who says semiotics is too academic, or who can’t envision how to apply it?

Rachel: Aside from showing them a case study like Charmin, another way to get people on board is to pass on some skills and get that person doing semiotic analysis for themselves.

The foreword for my first book was written by Daniel Sherrard, who works in advertising. When he was a new client of mine, I brought him to Winter Wonderland, which is an over-the-top, tacky Christmas festival held in London every year in Hyde Park. We went around, and I pointed out the semiotics of everything and how it all worked.

After about an hour or so, he was able to join in: “Oh, look at the semiotics of this ride.” We stopped and looked at a merry-go-round. He said, “Look at all the animals on this merry-go-round. They’re not horses, and they’re not dogs or cats. They’re all exotic animals: lions, tigers, zebras, unicorns.” I asked, “Why is that?” and he said, “Because it makes the ride more exciting, and it makes the whole event seem even more special. When will there be another occasion where you can ride on the back of a tiger?”

So, that is a brilliant way of selling semiotics. If you just spend time with people and teach them to do what you do, they will not be able to quit. They become addicted.

Zoë: The power of showing versus telling. Ending full circle where you began your journey, do you still publish within the academic community?

Rachel: I was going to say that when I retire, I will go back to academic research and publishing in journals like the British Journal of Social Psychology. But honestly, that’s not really true. I’ll almost certainly become a Twitch streamer. Let’s just be honest about that.

Gaming is quite a big part of my identity; I’ve been a gamer since 1991, longer than I’ve been in psychology. I’ve thought about making some content where I essentially play a variety of games while chatting about semiotics. Maybe our VIEWS readers could let me know if that’s of interest.

Zoë: I, for one, would love to watch a stream of you decoding the new Barbie movie. I’ll be sure to pass along other requests from our VIEWS community. In the meantime, I’ll leave you with a big thanks for sharing your wisdom with us!