By Amélie Truffert, Partner, Ordinary Differences, Cape Town, South Africa, amelie@ordinarydifferences.com

I’m going to use an old-school, trusted qualitative technique to open this article by asking you: “What comes to mind when I say, Africa?”

Stick with me, and take a minute to see what comes to mind. Hold on to those thoughts; we’ll come back to them.

For the past 10 years, I have lived across Africa—in Kenya, Ghana, and now South Africa.

The story I would like to share is about breaking the bias we might have when it comes to Africa and the people who live here. I want to challenge the common, negative narratives surrounding Africa and its people.

“Unconscious bias.”

I hear that expression a lot these days. Unconscious bias can create inherent prejudice and discriminatory behavior “through negative associations with a certain group or community,” according to Pragya Agarwal, author of SWAY: Unravelling Unconscious Bias (2020). Agarwal tells us that everyone has biases; it’s in our nature, and we can’t get away from them. But, perhaps, we can learn to become aware of our biases and attempt to readdress our thoughts when needed.

So, I’ve decided to take an uncomfortable look back at my biases before arriving here.

A Biased Perspective

I learned the market research ropes in Europe, and I assumed, naively, that I could simply replicate the same in Kenya (where I first landed in 2012). If it works in London, then it will work in Nairobi!

I shoehorned techniques and ways of working into a very different cultural context because, well, I thought my way was better. Trained as a researcher in London, I learned “cutting-edge” projective techniques from ice-breaking exercises, along with the latest trends and methods. It turns out that, no, my way was not better in Nairobi. It was different, for sure. I soon needed to learn about the ways of doing research in this new context.

In Kenya, participants expect a meal and a bit of a fuss to be made over them; after all, it’s a social gathering, and they don’t want to be rushed. People don’t want a “mzungu” telling them to hurry up as we start research in two minutes; a mzungu is “a wanderer” in Swahili and is a term often used to refer to a white person living in Africa.

People don’t mind staying longer and, in fact, often they want to. Adult participants want to chat after the discussion to find out about who you are; they are good researchers! Teenagers want to talk about fashion, music, and football.

In contrast, in London, I was used to people thanking me, getting their incentives, and rushing out to commute home. In Nairobi, Kenya, things couldn’t be more different.

Time is also more fluid in Lagos, Nigeria, than in the U.K.

If someone is late for a London focus group, the person will likely arrive flustered and apologetic. In Lagos, it’s perfectly acceptable for someone to be late. It’s typical.

At first, to a nonnative, this might come across as being rude or not concerned about the research. That’s not the case at all. Time isn’t strictly adhered to, but that doesn’t mean they don’t want to be there. Quite the opposite! Respondents arrive full of enthusiasm, raring to go. They are often thrilled to be asked their opinion on a particular topic. A planned two-hour focus group in Lagos often runs to three hours—if not more. The enthusiasm and exchange of ideas are thrilling as a researcher—I’ve rarely had such energy from Europe. I just had to reframe and learn to be patient.

Further, being on time in Nigeria is different from being on time in Kenya. I once sat with a South African client in Botswana, waiting for over two hours for the participants to arrive as it was raining. I didn’t realize that this meant they weren’t coming until the rain had stopped. Whereas in Kenya, the rain never stopped anyone from showing up.

Frequent Assumptions about Africa

I am, unfortunately, not alone in making huge assumptions about working across the continent. Here are some of the questions that I’ve been asked over the last 10 years, some as recently as six months ago (some questions were from fellow researchers, some not):

- “What’s Africa like as a country?”

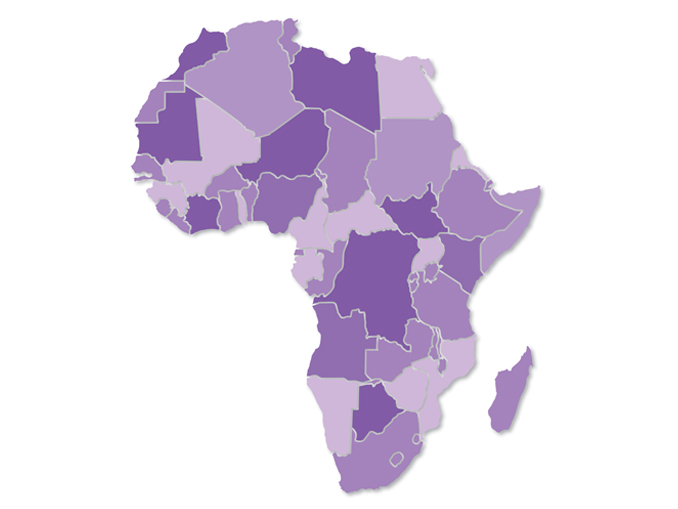

Plot spoiler, it’s a continent comprised of 54 countries that are often lumped together out of bias that they’re all the same. The misrepresentation of Africa as one amorphous space baffled me during the Ebola outbreak in 2015 in West Africa. I cannot count the number of times I was asked if I was safe (I was over 8,000 kilometers or nearly 5,000 miles away).

- “Do they have electricity there?”

Yes, of course, there’s electricity.

- “Do they have mobile phones?”

Yes, African countries have leapfrogged Western societies with their ingenious ways of using smartphones. A much-cited example is MPESA in Kenya—a service launched in 2007 by Vodacom to meet the needs of the population who needed digital financial services but who did not necessarily have access to traditional banks. MPESA is now a way of life for conducting commerce across a breadth of different socio-economic classes across Kenya and the region. The firm touts on its website that it has “51 million customers, $314 billion in transactions per year.” If, at first, it aimed to meet the needs of the unbanked population, MPESA is now used by everyone. You could take out life insurance or a bank loan via your mobile phone in Nairobi before you could in London.

“Can I do market research in one country and extrapolate the findings to the rest of the continent?”

“Can I do market research in one country and extrapolate the findings to the rest of the continent?”

This one makes me particularly sad. It not only assumes that all countries are the same but also reveals a lack of interest, curiosity, and energy about discovering the continent. Not to mention the lack of opportunity that unpicking the different cultures and populations could bring. Can you do research in Kenya and assume it’s the same for all other 53 countries? No. That’s like asking if you can do research in the U.K. and assume the findings will be the same for France. The distinction between these two is minimal. Imagine the distinction across North, South, East, and West Africa. This question particularly feeds into the bias that many have about Africa: it’s all the same culture, behaviours, issues, and solutions. Nothing could be further from the truth. Working in this industry should elicit some curiosity and desire to dig deeper than stereotypes, to reveal something new to researchers and their clients.

- “If I go to watch focus groups, will I be kidnapped because I am white?”

No, of course, you won’t be abducted just because you’re in Africa. There is the bias that Africa is inherently dangerous, unlawful, and unruly and that everyone is out to get you. Now, I wouldn’t recommend anyone (regardless of race) walk around, say, Cape Town, at midnight alone… just like I wouldn’t recommend anyone to walk around alone in London late at night.

These questions do not include the trove of hugely inappropriate racist “jokes,” such as “Will you have to fend off lions to get to your focus groups?”

Stereotypes Versus Reality

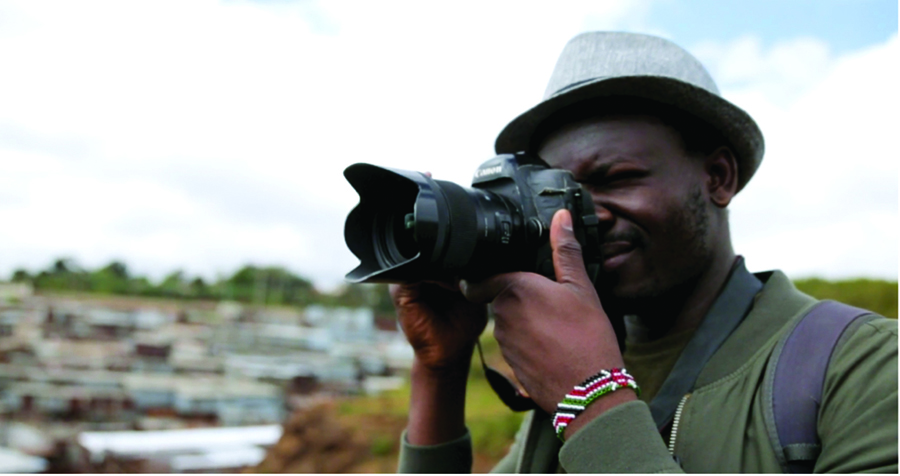

We did some work exploring creativity in Kibera, a large township in Nairobi, Kenya. As researchers, we wanted to bring the research to life by producing a short film. We wanted to show that Kibera was more than stereotypical images.

The documentary highlighted local talent, including a photographer who has had his work shown on CNN and BBC, a fashion designer who has had his clothes on a catwalk in Europe, as well as award-winning artists and musicians.

The film challenges the biases that people have of Kibera (Kenyans and other nationalities as well): that it’s a place of insecurity, crime, and poverty. It’s easy to let ourselves imagine this is all Kibera represents and shut down the thought that it could be anything different.

That’s bias: having assumptions—about which we’re often unaware—and accepting them as fact—even in the face of evidence that contradicts our bias!

When I showed this film about Kibera to some people, I was asked why I had “scripted” the story, as if they assumed someone from Kibera couldn’t possibly be eloquent or get his or her point across in a certain way. Or I was told these stories were rare, and we had purposefully sought the rare few who were doing something creative. Neither is true; we did not script the story, and we found many creative people in Kibera.

Of course, this bias goes beyond market research—this is about reflecting on yourself, on your inherited beliefs, of what your culture has told you to think about Africa.

The media has been rife with images and stories that portray Africa in ways that lead people in “Western” countries to dismiss the cultures, creativities, resourcefulness, and richness within the 54 countries in the second-largest continent in the world and home to 1.2 billion people. Consider, for instance, how the common charity appeals portray a certain image of Africa.

It’s hard to unlearn what you’ve seen.

Moving Away from Our Biases

Last year, Médecins Sans Frontières (or Doctors Without Borders) released a video and press statement apologizing for years of misrepresenting their work in Africa and other countries in the Global South.

The organization recognized that they were not sharing the full story to raise money. For example, in one of their ads, a small child is with his mother and father, who brought him into a clinic for treatment. The MSF campaign cropped the picture, removing the parents, to show only the white doctor and the small baby. This makes it appear that the baby is alone and utterly helpless and that the MSF doctor is the only one doing anything about it. They now recognize that these pictures propagate a single story and perpetuate racist stereotypes.

MSF apologizing is a big deal. It takes courage to admit you’ve not behaved appropriately. Of course, no organization is perfect, and no human being behaves in the right way all of the time. But to recognize their bias, how it demeans the lived reality of those it purports to help and publicly talked about it… we need more of this.

I’m not going to say that everyone is lovely, everyone is warm and friendly—because that’s feeding another bias, the bias that everyone is happy despite the struggles that (they are perceived) to be facing. That’s as lazy and untrue as saying everyone is out to steal from you. I will say that Africa and its countries are both multicultural and interwoven; the cultures, practices, values, beliefs, and ways of acting and being in the world change vastly from one corner of the continent to the other.

As qualitative researchers, we should always be neutral, open, and engaged with the people we talk to. That’s my philosophy—at least it is now, after years of confronting my own bias.

How often have I really been neutral? Probably never, as my own unconscious bias was often there. I’m trying to be more conscious of my potential for bias—more honest and, thus, vulnerable to them.

A New Perspective

Africa is experiencing a new focus. The world’s gaze is (finally) turning toward Africa.

Take Netflix, which will soon release a new series of modernized African folktales: African Folktales Reimagined, a series produced and directed by African teams. This would have been unheard of five years ago.

Let’s go back to my initial question: “What comes to mind when I say Africa?” In what ways has this article shifted your initial thoughts and the biases that you might have had?

As a reader, maybe you were already familiar with this more accurate picture of Africa. If not, and if you come across potential work in the region, I’d urge you to pause and reflect.

View Africa as a multifaceted, fascinating, and vastly different set of 54 countries, each with its own individual culture and population. Of course, there might be some crossover, but to lump them together does the continent—and the market research industry—a huge disservice.

Embrace the uniqueness. Instead of viewing particularities as a barrier to research, I’d urge you to lean into the uniqueness of the continent. For example, mobile phones are so much more here: your livelihood can be carried in the palm of your hand. It’s often the sole device used as a bank, a credit card, a TV, a movie-streaming platform, a music store, among all the other usual functionalities. Forget thinking of the participant as a multidevice, multiscreen consumer. Here, the mobile phone rules.

I know I have had a difficult and uncomfortable realization of my bias before and during my years here. I challenge you to reflect on your own. Please do leave a comment or reach out to me directly; I’d love to hear more about your questions, thoughts, and experiences with research in Africa, bias in Africa, or bias more generally!