By Christopher Frawley, Principal, Clientsong Insights, Miller Place, New York, chris@clientsong.com, @chrisfrawley

By Christopher Frawley, Principal, Clientsong Insights, Miller Place, New York, chris@clientsong.com, @chrisfrawley

To help clients assess the state of their experience from the customer’s point of view, it can be very useful to start by “walking the experience” yourself. We call this an “Experience Investigation.” An Experience Investigation is an evaluation of what it’s like to be a customer, to experience and see things from a customer’s point of view. This means that we act as a customer and go through the experience firsthand. In this way, we live the experience for ourselves.

The most important starting point for organizations that want to truly understand their customers (and make improvements) is having empathy. As a researcher who is going through the experience for yourself, you will be able to empathize with the client’s customers as you continue your research. Because the experience is embodied and internalized, it can add a depth and dimensionality of understanding that can’t be fully gained through interviews and other methods alone.

As a customer experience (CX) consultant who has engaged in Experience Investigations, I have identified a number of aspects that should be considered that help find focus areas for immediate action and additional subsequent research. Using this methodology, we pay special attention to the small signals that the organization is sending to customers during an experience. These act as subtle clues that customers perceive but are often not consciously aware of that contribute to how they feel.

In this article, we provide some tips for conducting your own firsthand Experience Investigation and how to more consciously notice the stimuli that contribute to how customers might feel in their experiences with the client organization.

When to Use the Experience Investigation

An Experience Investigation can be useful as a stand-alone exercise to help clients get a quick pulse on what’s working and not working in the customer experience, or most often a precursor to additional qualitative methods. As a start, this methodology applies when the researcher can act as a customer, which is most often in a business-to-consumer (B2C) scenario. This approach can be applied to selected parts of an experience or the overall customer journey.

You would use an Experience Investigation when:

- You want to look for things that might impact a customer, but they would not necessarily reveal in an interview or survey. For example, the extra time it took to look up something needed for an online application or to find a contact number.

- You want to identify where the peak positive and negative emotions are likely to occur. Using your own observations, you will likely be able to notice the high and low points.

- You want a better understanding of the process steps in an experience. It’s one thing to hear the process described and another to go through it. This will give you a jump-start when talking with customers later.

- You want to perform a quick study of the experience with a client competitor prior to recruiting competitor customers for interviews.

Example: When conducting an Experience Investigation for a leading online banking client, we found several time-consuming process steps that weren’t mentioned by clients in interviews and were later identified as a drag on the experience.

It should be noted that this approach can be applied successfully to both online and physical customer journeys. In the online world there may be fewer auditory and sensory clues to notice, but certainly visual, navigation, and language aspects take center stage and will be common with physical experiences.

What the Experience Investigation Gets You and Does Not Get You

What you get from this approach: a holistic picture of the experience as seen through a customer experience lens—one that incorporates rational, emotional, subconscious, and behavioral aspects.

What you do not get from this approach: the perspectives of additional customers with a range of experiences and a more detailed accounting of how a much larger group of customers or customer subsets perceive the experience.

These insights can help clients take near-term action where they think it is appropriate and, more importantly, suggest where additional research is needed to confirm the hypotheses generated from the researcher’s immersion in the experience.

The Number of Sample Experiences Depends

This depends on the client’s goals and scope. Are we looking at the overall customer journey, or parts of it? Which customer channels are important?

Once you have established the target scope, we find that up to a half dozen sample experiences for each specific focus area should provide enough information for a valuable reading.

Dimensions of the Experience That Should Be Considere

In an Experience Investigation, we look closely at the following aspects:

- Expectations—What do you expect as a customer?

- Actions—What happens?

Emotions—How do we feel as the customer? - Subconscious—What are the clues and signals in the experience?

- Behavioral Psychology—What cognitive biases are at play?

These aspects of the experience are your checklist of things to observe, and they inform the questions to develop for an interview guide.

Expectations

Putting yourself in the role of the customer starts with thinking about what is expected.

- What are your goals for the interaction?

- What do you think should happen?

- What do you think will happen?

- Are the things that should happen and will happen different? If so, why?

Then evaluate:

- Did the experience follow a direct line? If not, where did it veer and why? Did the experience veer to benefit you (as a customer) or the company?

- What was the feeling you had when this happened?

Actions

What happens on a rational and conscious level? What is the back-and-forth interplay between you and the organization?

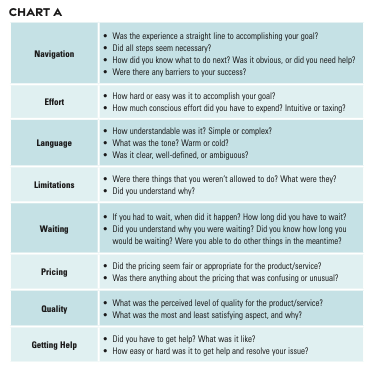

We recommend writing down what happened as a sequential story. See Chart A for some important things to observe.

Emotions

While most experiences we have with organizations fall in a relatively neutral emotional band—not exceptional, not terrible—there are certainly situations where we feel positive or negative at different points in the experience and overall. The extent to which we feel emotions will directly affect how well we will remember the experience.

In response to the things that happened, what feelings came up? How strongly did you feel about them? What specifically contributed to those feelings? If there were emotions at different points in the journey, what were they?

When did the strongest emotion (positive or negative) occur?

What was the emotion at the end of the interaction?

Subconscious

There is a world of inputs in our experiences that mostly fly “under the radar” and away from our conscious attention. These signals could be in the physical environment, on a voice or video call, or online (desktop or mobile).

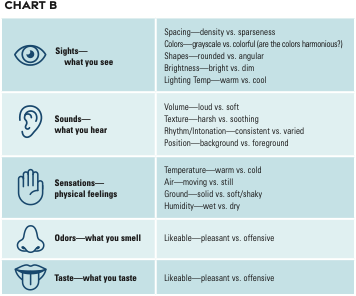

These all have impact in the perception of the experience, whether they are strongly differentiated or not. To understand how these might impact customers, we must draw our conscious attention to these signals (see Chart B).

Some things are easier to notice—an indifferent cashier, a typo, or a list of choices that don’t apply. Some are a bit harder to spot but still make a subconscious impression—a slight distortion in the loudspeaker, a napkin holder that’s almost empty, or lights that are a bit too bright.

Trying to pay attention to everything all at once can be overwhelming. However, if you can keep some of these inputs in mind, try simultaneously scanning for everything and nothing, and then note what pops into your attention; be sure to “note” that in your research log.

Our subconscious mind is keeping track of things whether we realize it or not. It’s as if the things you perceive make an impression in a hidden ledger. In addition to the rational and conscious experience, this hidden balance sheet provides valuable clues as to why customers feel the way they do.

Behavioral Psychology

What concepts of behavioral science are noticeable in the experience? Our understanding of cognitive biases continues to expand, and many organizations put these principles into action in their customer experience. If this is a new area for you, we recommend familiarizing yourself with some of the most common concepts like loss aversion, scarcity, choice overload, and social proofing.

Capturing and Documenting Your Observations

There’s a lot of information to pay attention to, so it’s useful to capture as much as you can—both on the fly and immediately afterward. Here are some suggestions for capturing your observations.

A Templated Worksheet

To track all these things, it’s useful to create a worksheet or template to capture your thoughts as you go through the experience.

A Camera (Your Smartphone Will Do)

This is very useful because you can show pictorial evidence of what is going on in the experience. It will also remind you of what you saw. Still photos or videos shot with your smartphone work fine. Be sure to secure permission when photographing people whose faces are visible.

A Voice Recorder (Your Smartphone Will Do)

If the situation allows, you can record your thoughts as you go through the experience. You might also provide your thoughts immediately after parts of the experience. You can use your template as a checklist as you go. You may also want to capture some of the sounds of the experience. You should make sure to gain permission if you are recording someone with the intention of using the sound clip later.

A Partner(s) (Optional)

Having an additional partner(s) is highly dependent on the scope of the project—how many observations need to be conducted and the project budget. Executing an Experience Investigation with someone else working with you can add depth.

If you work side-by-side in the field, you can trade observations on the fly and better document the experience as it happens. If you work separately in the field, you can theoretically cover twice as much ground.

In any case, if working with a partner, there is value in working closely when preparing the findings.

Putting Things Together

After reviewing your observations, there will be items that stand out as interesting or important (e.g., more emotional weight, more awareness of subconscious inputs). As you spend time with your notes and these observations that stand out to you, you’ll often find at least one conceptual theme emerge from those standout items.

Often, it’s best to center your key findings around these themes. It can be quite useful to additionally present your findings through the lens of the customer journey.

For the journey portion of the report, it can be helpful to provide ratings or icons across the journey steps to make the information easier to absorb and potential interventions more immediately identifiable. The scoring here will be somewhat subjective. It will be more impactful to include both a more rational aspect like level of effort (i.e., ease, difficulty) and an emotional rating (i.e., frustration, excitement). These will be based on your own observations.

It’s also important to highlight areas of positive observations so the findings appear in the context of leveling up the existing experience, continuing and expanding on those aspects of the experience that may be working well for customers.

Remember that your deliverables are meant to be directional and not definitive. Your observations may appear somewhat subjective, and that’s to be expected because that’s exactly how customers perceive things as well. In this case, as a skilled researcher, your observational antenna is trained to notice more of the things that customers and employees glaze over, but still impact the emotions that keep customers closer or drive them away.

Because it starts with empathy, a well-executed Experience Investigation will offer a high-definition view of the existing customer experience, highlighting areas for additional focus, research, and intervention, and, most importantly, create the necessary organizational empathy for the customer’s point of view. That empathy is key to designing and improving products and services (and the experience that surrounds them) in ways that engender customer loyalty and engagement.