By Oana Popa Rengle, Founder, Anamnesis, Bucharest, Romania, oana@anamnesis.ro

Note: This article was written on April 2, 2022, and events on the ground may have evolved.

In Sighetu Marmației, a border-crossing town in Northern Romania, a bridge connects Romania to Ukraine. Since March 2022, this bridge has been lined with toys from one end to the other. Every refugee child from Ukraine, on entering Romania, can pick a soft, huggable little object, a doll, a stuffed animal, or even a small toy car and keep it.

Between February 24 and April 1, 630,000 Ukrainian refugees have crossed into Romania, many via this bridge. Because of the Ukrainian martial law preventing men between 18 and 60 years old to leave the country, half of the Ukrainian refugees are children who have hurriedly fled to safety, many times with little more than the clothes on their backs. Their own toys were left behind, at best in an empty house that will remain empty for a long time, at worst under the rubble of bombing.

Their new “bridge” toys are literal transitional objects, glimpses of hope that they are crossing not into a foreign and scary land but into a place of some comfort and security.

Sighetu Marmației, Romania, used to be a quaint, quiet border crossing point. But, on February 24, there was a dramatic change on both sides of the bridge. While on one side long lines of desperate, exhausted, freezing mothers, grandmothers, and children were forming, on the other side, humanitarian volunteer efforts were mounting. It was the volunteers, the regular people, the local communities, and the local church groups that got organized first, even before the government and other authorities.

On February 24, some everyday Romanians who woke up to a new reality, worse than the one they had gone to sleep with the night before, got in their cars and simply drove to Sighetu Marmației to see how they could help. The same day, people from local Romanian communities went to the border road with hot coffee and tea. Someone set up an ad hoc kitchen and started cooking warm meals for the hungry, tired women and children. As days progressed, things got a bit more formally organized—but in the first few days, it truly was a grassroots effort by everyday Romanians.

One of them was a father who mobilized a group of local people, nongovernmental organization (NGO) volunteers, and border guards to line a bridge with toys and transform it into a small crossing of hope.

The Empathy Crisis of the Modern World

For the longest time, psychologists have warned of the “crisis of empathy” facing our society. One study, published by a group of researchers from the University of Michigan, found that the average level of “empathic concern,” meaning people’s feelings of sympathy for the misfortunes of others, declined by 48 percent between 1979 and 2009, with a particularly steep decline between 2000 and 2009. To be frank, we don’t need scientific studies; you just need to read the comments section of any article on social media to be completely mortified by the blatant lack of empathy on display.

Then, how do we explain the huge displays of empathetic concern toward the drama of the Ukrainian people, all over the world? Is the unexpected occurrence of such a terrible human tragedy refilling the world’s depleted reservoir of empathy? Is the decline trend going to shift?

With these questions in mind, I talked to a few people who were involved in different ways in the humanitarian relief efforts. As a qualitative researcher, it is not surprising that I reached out to the (qualitative) research community—both because they were within my reach, and also because who would be better experts on empathy?

Paul: CEO of Refugee Support Europe

Paul Hutchings is the CEO of Refugee Support Europe, an international volunteer organization; before that, he was a market researcher for over 20 years. In the early days of the war, he had travelled to Moldova from the U.K. to help with the humanitarian crisis. Moldova is the neighboring country that has received the highest number of Ukrainian refugees as a percentage of its own population. By the end of March, almost 400,000 refugees had crossed into the small republic of only 2.5 million inhabitants.

Paradoxically, this sudden, huge influx of people was not visible on the streets in the early days of Paul’s arrival in Chișinău, the capital of Moldova. While it took time for the institutional help to get established, average Moldovan citizens had taken it upon themselves in a grassroots effort to host many of these women and children in their own homes. This effort was confirmed by supermarkets selling out of buckwheat cereal, a Ukrainian staple, and the need to begin rationing sugar and cooking oil.

Paul was under pressure to set up his organization’s operations urgently because he was aware of the large personal cost for the Moldovan population. “Hosting a Ukrainian family in their home means paying for more electricity, more gas, more drinking water, more food, plus taking time off work to assist with other needs of those hosted.”

Cristi: Insights & Analytics Manager

Cristi Ghiță’s day job is as an insights and analytics manager for a major corporation. Throughout the month of March, he woke up every morning at four o’clock and headed to Gara de Nord, Bucharest’s major railway station. Bucharest is the main railway node of Romania, so the route of Ukrainian refugees toward various destinations in Romania or other parts of Europe passes through here. It soon became the common-sense meeting point of people who wanted to volunteer to help with the humanitarian crisis.

Every day, ten trains would arrive in Bucharest from various border points in North and Northeast Romania, most of which were overnight trains. At first glance, they would appear to be regular commuter trains with people quickly getting off and walking across the platform, ready to start off their day outside the station. Then, after a short pause, the platform started filling up with Ukrainian refugees—women, children, and piles of belongings they managed to carry with them. An estimated 100 to 400 refugees were on each train. Many had no clear destination, or plan, or place to be. At the end of what must have been a three- or four-day trip with a lot of walking by foot and sleeping in improvised conditions, they were exhausted, cold, and confused. That’s where volunteers came in.

“On my first day,” Cristi says, “I just came in and asked, ‘What can I do?’ I was told to put on a vest and figure out where I can help.” He became a sort of concierge for the people getting off the trains. He’s done everything—from carrying luggage, carrying people, carrying various crates of donations, handing out food and drinks, hailing cabs, setting up tents, etc. Often volunteers chip in to buy train tickets or pay cabs, as people coming in didn’t have enough or were very reluctant to spend the little money they had. (Fortunately, railroad transportation soon became free for all refugees; and many average Romanians, including taxi drivers and small entrepreneurs, offered free transportation services.) “I’ve seen families where all they had were coins taken from children’s piggy banks. I’ve seen a woman who had left with nothing—her young baby was still wearing the dirty clothes he was wearing when she pulled him out of the rubble of their house.”

Hana: Founder of Confess Innovation

Hana Klouckova is the manager and founder of research company Confess Innovation in Prague, Czech Republic, and a long-time QRCA member. She is also one of the many people who, in the first weeks of the exodus, hosted a Ukrainian family in their homes.

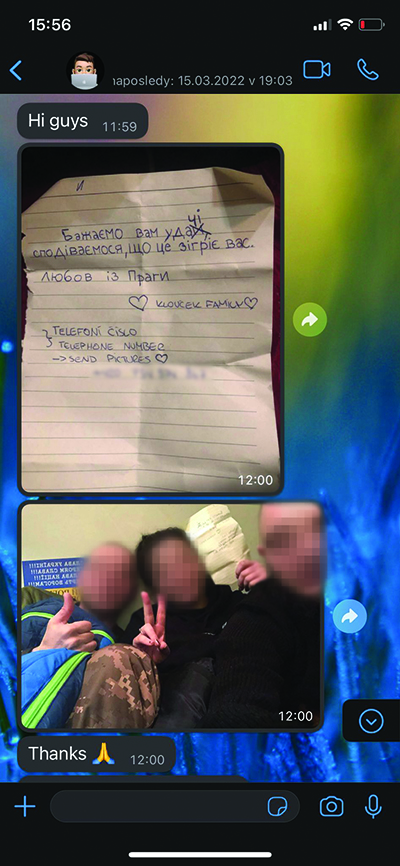

Hana’s 17-year-old daughter, Adela, was the driving force behind the Klouckova family’s efforts to help. After overcoming the initial shock of the war and the numbing fear of “What do we do if this war extends to the Czech Republic?,” they focused on helping. It started with money donations, and then with buying camping mattresses and sleeping bags. Adela had the idea to write letters and put them into the sleeping bags. “We are thinking of you, we hope you are safe, and you will be warm sleeping in this sleeping bag.” She also left her own phone number with the letters (and got answers—see the picture).

Hana’s 17-year-old daughter, Adela, was the driving force behind the Klouckova family’s efforts to help. After overcoming the initial shock of the war and the numbing fear of “What do we do if this war extends to the Czech Republic?,” they focused on helping. It started with money donations, and then with buying camping mattresses and sleeping bags. Adela had the idea to write letters and put them into the sleeping bags. “We are thinking of you, we hope you are safe, and you will be warm sleeping in this sleeping bag.” She also left her own phone number with the letters (and got answers—see the picture).

Then, they registered their spare room with the Ukrainian Embassy in Prague so they could host a refugee family. They ended up hosting Natalia, a 41-year-old hairdresser, her teenage son, Marko, and their dog. They fled the Ukrainian city of Kharkiv and had to transverse through the countries of Moldova, Romania, and Slovakia before arriving in the Czech Republic.

Hana says that on the first night, Natalia and Marko “were under such extreme stress that they couldn’t even eat anything. I didn’t understand why at first… it was pizza, everybody likes pizza, right?”

It soon became clear to Hana’s family that hosting a refugee family meant more than offering a spare room. Natalia moved out of the spare room after three weeks, but Hana continued providing daily assistance to help her become independent. “It’s a full-time job,” Hana says. First, a lot of support was needed regarding paperwork so they could stay and work in the Czech Republic. Hana has already organized a collection and purchase of hairdressing tools so that Natalia has the tools she needs to exercise her profession when she is able to. Then, they will need medical care to deal with some of the physical and emotional trauma of fleeing the war. They will also need to be accompanied to several doctor appointments. On top of that, there is also the issue of sorting out schooling options for Marko.

Disaster Response: Zunin and Myers Model

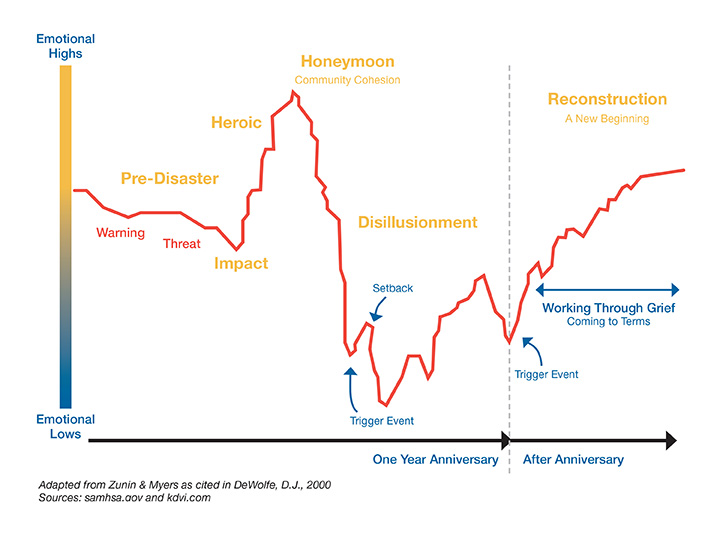

The model developed by Zunin and Myers more than 20 years ago shows that the response to a disaster follows a sequence of eight psychological stages: warning, threat, impact, heroic, inventory, honeymoon, disillusionment, and reconstruction.

According to this model, the early compassionate reaction is normal and expected in cases of disaster—it’s human nature. Right after the impact, there is a counterintuitive emotional high, both on the side of the survivors and of the external public response. There is a hit of adrenaline used for survival and rescuing. There is an all-time high “community cohesion” peak, called the honeymoon phase, characterized by compassion, tolerance, and hope.

Sadly, after this peak, a decline inevitably follows. Both survivors and helpers become confronted with the limits of the resources available—whether time, material, or psychological resources. On the impacted communities’ side, hope and optimism gradually turn to grief and anger, while in the public response, we start seeing the phenomenon called “psychic numbing”—a “turning off of feelings” first noticed in rescue workers in the aftermath of Hiroshima.

The response to the Ukrainian crisis does confirm the three factors that naturally play up empathy in humans:

- similarity

- past experience

- familiarity

There has been a lot of conversation in the public space on how the victims were perceived as “people like us” in the Western world, hence causing a stronger compassionate reaction than in the case of other wars in recent years. I believe:

- Familiarity played a role also, as we tend to be more empathetic toward people who are familiar to us. The initial wave of Ukrainian refugees fled into countries that already had large immigrant Ukrainian communities.

- Similarity in this case might go even beyond ethnicity or race. The specific threat posed to the entire world by this particular war brutally confronted more people in the West, with the fear humans are most adamant to avoid—the possibility of their own death. In these cases, people’s worldviews are strengthened, and there is a shared increase in group identification with the victims (Pyszczynski, 2004).

- Past experience is a trigger I can testify to. Even though I have not personally lived through war in my country, I did grow up with the collective transgenerational trauma of the Russian domination/occupation, and I live the misfortune of the Ukrainian people with a particular tender sensitiveness and terror.

All these factors also help in examining the paradox of how the larger the number of tragedy victims, the disproportionately lower the compassionate response; humans are hard-wired to react to other humans (to individualized stories) they can relate to, not to abstract large numbers.

Is the World’s Empathy Reservoir Refilling?

Probably not. Or, if it was, it was just temporary.

But also, the reservoir metaphor might be wrong. An alternative school of thought in the research of empathy looks at it not as a resource that fills up and gets depleted, but as a choice people make based on personal and cultural values. For example, there are studies showing that people in strongly collectivistic cultures do not feel the lower compassion toward mass suffering mentioned above.

So, maybe the right question is whether this terrible event can produce a shift in culture? Will it impact people’s individual values? The most likely to be impacted in this way are those in their formative years—adolescents like Hana’s daughter. As a qualitative researcher, I am most curious how this young generation is imprinting the terrible events of 2022, and how the “humanity at the edge of war” that they have experienced will shape their (and our) future.

How Can We Best Help? (Learn from a Former Qually)

“Aid with dignity” is the philosophy of Paul Hutchings’s organization, Refugee Support Europe. It is a good example of the kind of empathy that our qualitative profession is tasked with—the one that enables action upon understanding the intricacies and complexities of human nature. (It makes me so proud to know that Paul is one of us quallies.)

When we talked, Paul was setting up a “Dignity Centre” in Moldova, a shop space that gives away food and necessities in a manner people would use if they went shopping in their hometowns: by browsing shelves, considering what they need, comparing options, etc. Some needs are more visible than others; but being a refugee also strips people of their dignity, and Paul and his volunteers made it their mission to restore some of that.

They also consider the needs of the local communities that host refugees—those communities who come together to help during the heroic phase but are faced with depletion of resources once they cross the “honeymoon” peak. Paul knows that in the face of increasing material and psychological pressure, questions of “Why help them and not us?” often arise. Therefore, they prioritize sourcing products, i.e., directing their money to local businesses. It is not just practical—buying the things people need, when they need them—but a better fit to the whole ecosystem.

This is just one reason why (in the medium and long term) the best way regular people like us can help is with money. People often feel that giving money is not help enough, and they want to put more of themselves on the line—as Hana and Cristi surely felt.

In the beginning of the crisis, this informal manpower is crucial. But there is also, as Paul puts it, “chaos, chaos all the time.” While this is time abundant in generosity, planning and organization are in short supply. This causes many resources to go to waste. Once experienced organizations are set up, they know how to organize the humanitarian effort in the best, most time-sustainable manner. But experienced organizations need money to function.

So, if you do not have the energy to spend four to five hours a day in a refugee arrival center before your corporate job, nor do you feel comfortable hosting a stranger in your house, don’t think that making a money donation to a trusted organization would be insignificant. It can change a person’s life. If you choose to donate to Refugee Support Europe, here is a link:

www.refugeesupporteu.com/ukraine

References:

- Changes in Dispositional Empathy in American College Students Over Time: A Meta-Analysis, Konrath, S.H., O’Brien, E.H., Hsing, C., Personality and Social Psychology Review, August 2010, Advance online publication.

- What are we so afraid of? A terror management theory perspective on the politics of fear, Pyszczynski, Tom (2004), Social Research: An International Quarterly 71 (4):827-848.q