By Mary Ellyn Vicksta, Vicksta Innovative Practices LLC, Appleton, Wisconsin, mev500@yahoo.com

Author’s note: I share this approach of sequencing, which I fully explain in this article, coming from the perspective of being deeply involved in the corporate world of marketing research, as a meeting facilitator, and as a photographer.

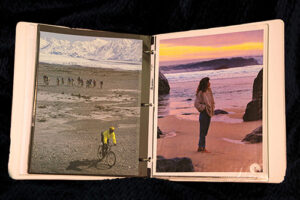

Like many marketing researchers and facilitators, I use photos and visuals during focus groups and facilitate meetings in order to prompt responses. In the beginning, I would cut photographs out of magazines and have a “photo deck” with images that were close to the topic being discussed and some that weren’t related at all. This worked well for many years, and I appreciated the keen insights that the photos prompted (See image A).

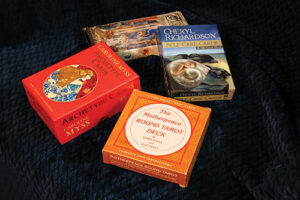

In my own facilitation work, I played around with using photo decks of various kinds, from Visual Explorer to tarot cards. I had respondents pick cards that would reflect the beginning, the middle, and the end of their use of a particular product, and then tell a story about it. Without realizing it initially, I was using the concept of sequencing, championed by Minor White, an American photographer and editor. It’s amazing what the subconscious can do (See Image B).

I first became acquainted with White’s sequences while I was in college and took a photography tutorial during the last semester of my senior year. I was exploring several famous photographers and the various ways in which they approached their photographic craft.

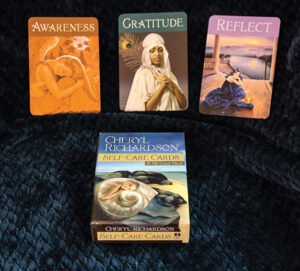

Dictionaries define a sequence as “the following of one thing after another; succession” or a “continuous or connected series”—these are the general definitions I was following when I first asked participants in my facilitated discussions to pick beginning, middle, and end cards from a photo deck (See Image C).

White, however, took this dictionary definition and transformed it. He was influenced by another famous photographer, Alfred Stieglitz, who believed strongly that a photo stands for something other than the depicted subject matter. Stieglitz was also interested in the ordering of photos, especially when visiting an art gallery and seeing the sequence of art as he walked through. White took the concepts of “ordered matter” and “order creates deeper meaning” and made them a central part of his life’s work.

According to Paul Martineau, associate curator in the Department of Photographs at the J. Paul Getty Museum, in his book Minor White: Manifestations of the Spirit, “Viewers of his sequences must not only read each individual image in relation to adjacent images but also consider all of the images in the highly structured grouping as the complete expression of an idea.”

White explained, “To engage in a sequence, we keep in mind the photographs on either side of the one in our eye.” It is this combination of the photograph’s underlying meaning and the ordering that made White’s sequencing special and transformative in providing deeper meaning.

According to Peter C. Bunnel, photographic historian, former curator of photography at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, and former professor of photography and modern art at Princeton University, in the book Minor White: Manifestations of the Spirit, “White’s sequences have many levels of meaning, but these can generally be categorized into three main groups: superficial, underlying, and ultimate. The superficial meaning is descriptive; the underlying meaning is symbolic; and the ultimate meaning is intensely personal and thus the most elusive.”

These three levels of meaning—descriptive, symbolic, and ultimate—caused me to think differently about the use of images in my own practice. I started to look at the meaning of the whole sequence, as well as different interpretations based upon different orderings of the photos/cards, and always dug deeper.

A Personal Example of Sequencing

To illustrate how a moderator or a facilitator might use sequencing to dive into a deeper meaning, I will first use a personal example. This is an example of looking for ultimate meaning that is “intensely personal and thus the most elusive.”

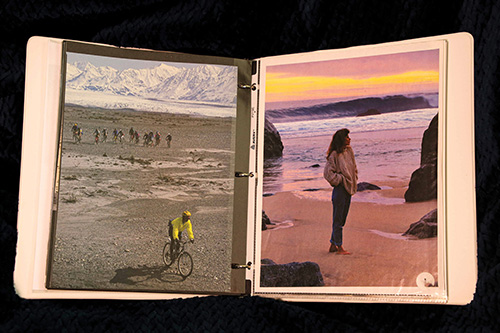

I’ve been doing a lot of walking lately and taking photographs while I walk. Like most of you, I usually travel a lot, but during the first year of the pandemic, I spent most of my time around my home.

I used sequencing to help me understand a bit more about why my geographic area is so important to me. This question continually occurred to me during my walks and was something I was pondering post-walk when I looked at the photos captured during the day.

When I was first selecting my own photos for my sequence, I selected those that represented a pathway in some way (See Image D). At first it was an unconscious decision to take this kind of photo. But after really looking at the photos selected and asking myself some questions, I was able to start pulling together some meaning. It moved beyond pathways to represent the historical perspective that each photo suggested.

I did some searching online and found a historical photo of the first house deed in our area. That deed was claimed by a fur trapper and his family whose trading business was successful enough to build an elegant house in the Wisconsin wilderness in 1837, eleven years before Wisconsin became a state. I pulled the last photo from the sequence and new meaning emerged. (See Image E.)

The big “aha” to me related to the deep sense of area history that was literally underneath my feet. Besides the first house deed, a few blocks away from my home was the first house in the U.S. with hydroelectric power using the Edison system and a whole host of former paper mills and woolen mills along the Fox River. This led me to develop a great appreciation for the locks and dams along the Fox River that made transportation and power available for industry. This then led me to the insight that my career was made possible because of a former paper company that morphed into consumer products.

From this, I came to a much greater appreciation of where I live, where I work, and where I consider home to be. Now, each time I walk along the river, I am reminded of its rich history. These insights are now a part of who I am and add to the concept that Appleton, Wisconsin, is my hometown.

Thus, sequencing allowed me to deepen my understanding and put the elusive into words—White’s third level of meaning: the ultimate.

Example of How to Use Sequencing from Professional Practice: Shopping Experience

About ten years ago, I was involved in a number of shopping-related ideation sessions. I was the facilitator and was responsible for crafting some experiences that would help us understand our shoppers better and how shoppers navigate through stores.

The word navigate suggested a sequence to me. A sequence that would be based on time. I sent the participants out to several different stores with the task of documenting their navigation through the store. At this point, it was pretty straightforward ethnographic research—observing and experiencing a journey. In this case, it was a journey through a store.

The actual project was associated with grocery, but we looked at other types of stores to get a sense of their navigation patterns.

The task was to work as a small group of three and experience a shopping journey within clothing, sporting goods, or books. Each person in the group went on a solo shopping journey in the assigned store and took photos of what caught their eye about the journey.

The small group reconvened, went through their individual photos, and created a group version of the store’s journey. Each group sent me a short PowerPoint presentation showing a progressive journey through the store. During the presentation, those who weren’t in that particular store journey were asked to take notes on what they saw, anything they would change, or anything they would recommend utilizing in a grocery store environment.

Then a different group went through the deck and rearranged the slides in a different sequence, an ideal journey. This new PowerPoint journey was then shared with the larger group, and everyone in the room was asked to capture ideas about an ideal journey that might happen in a grocery store.

The result of this exercise was three different store journeys that were shared with the grocery store, one of which was implemented.

Given what Bunnel said about White’s work, this can probably be seen as a descriptive use of sequencing: taking a deep, descriptive dive into several different journeys in order to discover new patterns and approaches.

Example of How to Use Sequencing from Professional Practice: Consumer Reaction to Packaging

In this project, the focus was on the product package and how the package was used throughout the entire product experience. The package designers had intended that the package not only keep the product “sanitary” inside a consumer’s purse or backpack but might be used for “clean and discreet” disposal of the product.

Consumers were invited to individual interviews twice. In the first interview, consumers were asked to talk about their product experience and get instructions about taking photos or a short video with their phones to document their use of the experimental product. In the second interview, they were asked to talk about their photos and what the photos conveyed about their whole product use experience from carrying the package all the way to disposal of the product after use.

Ironically, the use of the package was pretty similar among the participating consumers. However, in talking through their photos, their feelings about the product experience were more richly and deeply conveyed when they created a sequence that was not a sequence in time but a continuum of feelings from “lousy experience” to “fantastic experience” with a clear reason why along the continuum. The package designers were able to take this input and markedly change the package design.

The added benefit was that the second discussion dove deeper into the symbolic meaning—the relationship of use of this product with mothering and caring for their young child.

Summary

Sequences can be tapped for three levels of meaning: descriptive, metaphoric/symbolic, or deeply personal. I found the use of sequencing to be extremely helpful to get to a deeper meaning—whether that is with consumers or with clients as they develop products or services. I also found that using Bunnel’s three levels of looking at White’s work to be instructive in designing the use of sequencing during a consumer focus group, individual interview, or during a facilitated ideation session. This technique has made a profound impact on me, bringing new insights to my personal life, as well as my professional life.

Be the first to comment