by Zoë Billington, User Research & Customer Insights, Santa Monica, California, zbillington@gmail.com

Nancy Cox shares a fresh perspective on thinking and writing like a storyteller throughout the consumer research and product innovation process.

Prologue | The Role of Storytelling from Ghost Writer to Product Innovator

Roses are red, violets are blue… Even though somebody else wrote this card, doesn’t it feel like I wrote it for you?

Nancy Cox did not compose this cheesy but accurate rhyme—I did, and I’m no card writer—but it illustrates her challenge during her Hallmark Cards career. “I was a ghost writer for other people, [writing] a card between two people who I haven’t met, but hopefully I have studied them enough for my writing to become a bridge between people.”

Her job was to help people tell a story—of their love on an anniversary, their best wishes on a birthday, or condolences during a time of grief. She had to do this without knowing them or the circumstances that led them to the card aisle, which now presented them with the daunting task of opening cards until landing on the one that expressed what they didn’t even know they wanted to say. Enter customer insights.

The need to get inside the heads of card-buyers, and to be an advocate for their needs within Hallmark, led Cox from copywriting to product development, merchandising, innovation strategy, and ultimately to customer research. Cox explains that “just like the bridge between two people through a card, researchers are bridges between businesses and customers,” and the power of storytelling was her primary means for constructing this bridge.

Composing a New Narrative around Storytelling

If you’re like me, you’ve heard the concept of “storytelling” thrown around a lot these days. You know that storytelling is the key to “bringing your products to life” or “inspiring your stakeholders to action,” but:

- Do you consider yourself a storyteller?

- Do you know how to tell a good story and when to make use of storytelling techniques?

Telling a data-driven story is always important when sharing customer insights, and Cox certainly does use and recommends using story for these purposes. But Cox is working to push the practice of storytelling a step further by demystifying story and using story earlier in the research process—all with the ultimate goal of democratizing the power of story for all.

Today, as founder of Research Story Consulting, Cox uses her talents to help a variety of aspiring storytellers, from brand managers to doctors, tell their stories. Her expertise lies in helping people find the stories in their data and empowering people who do not see themselves as writers to communicate these stories more dramatically.

Cox shared four storytelling takeaways:

- You—yes you!—are a storyteller

- Not every story has a hero

- Think beyond traditional frameworks

- Use story sooner than later

Chapter 1. You Are a Storyteller

Cox wants to bust open the myth that good storytelling requires advanced writing skills.

“People come to my workshops saying, ‘I went into science because I’m not a writer,’” explains Cox. These people include doctors and engineers who never thought of themselves as writers. But once they learn writing techniques, their natural storytelling abilities—attention to detail and ability to explain complex processes—shine through.

“There’s this internal talk that says, ‘I’m not a writer, I can’t tell a story.’ So I’ve learned to separate the two.” One way Cox does this is by teaching basic principles of craft, content, and genre. For example, craft reveals techniques such as writing left-branching or right-branching sentences.

“I promise that no one has to diagram a sentence!” says Cox. “It’s simply remembering that we read left to right, although this can vary by culture.”

As Cox explains, researchers have a natural tendency to build left-branching sentences with lots of modifying clauses before the main point. That’s the structure of academic writing. But left-branching structure can weaken your point. Cox asks us to compare these examples:

Several years ago, Americans across the country, not just in the Southwest, replaced their former top condiment, ketchup, with salsa.

That’s a left-branching sentence. The right-branching version?

Salsa replaced ketchup as America’s top condiment several years ago, a nationwide trend beyond the Southwest.

Cox points out, “The right-branching version states the main point first, is shorter, and reads faster because our natural tendency to pause at commas does not happen until near the sentence end.”

These simple techniques are proven to work. “Engineers have come to me with their arms crossed saying, ‘I dare you to make me a writer,’” says Cox. “But by the end of a workshop, they look at their work and can see, ‘I am a writer.’”

Chapter 2. Not Every Story Has a Hero

Cox has seen researchers struggle to fit their data into one of the predefined story frames that they think they’re limited to. Cox suggests a different approach. “Sometimes story technique is simplified to a story arc with a protagonist and antagonist. That might be appropriate in some cases, but there is a lot more to telling a story. The hero’s journey might work for some data, but it might not always be one of those classical frames,” she explains.

Chapter 3. Think beyond Traditional Frameworks

Instead, Cox also encourages her clients and partners to look outside these traditional frames to places like pop culture to unlock other ways of telling a story. For example, March Madness is a story frame for ranking; Shark Tank is a story frame for business persuasion. Each represents a commonly understood story frame that even when taken out of its original context, has universal meaning. Asking users to share their feedback in the context of a story frame yields greater engagement and therefore more useful insights from users and stakeholders alike.

Instead, Cox also encourages her clients and partners to look outside these traditional frames to places like pop culture to unlock other ways of telling a story. For example, March Madness is a story frame for ranking; Shark Tank is a story frame for business persuasion. Each represents a commonly understood story frame that even when taken out of its original context, has universal meaning. Asking users to share their feedback in the context of a story frame yields greater engagement and therefore more useful insights from users and stakeholders alike.

Cox has brought March Madness brackets into online qualitative and quantitative research as a means of having users rank their favorite concepts, using a framework that they are familiar and engaged with. “It’s basically a ranking, but it reveals much more. [Users] tell you the story of why they vote and why they want something to win. It’s so much more exciting and engaging.”

Not only does she use brackets with consumers, she uses them in parallel with internal stakeholders as well. Cox did the same bracket exercise with her Hallmark colleagues, creative agency, and users in separate groups. As the “madness” progressed, she displayed the brackets in a conference room for everyone to walk by and see which concepts were “winning” across the three different test groups. “People would walk by and see the bracket story play out. It was amazing to see the cheering and the biases revealed.” This meta storytelling technique encourages participants to explain their preferences through story and allows a story of those results to play out before stakeholders’ eyes.

“I want to relieve people of the fear of having to find a protagonist and antagonist in a bar graph—that’s not the only way to tell a story,” she says.

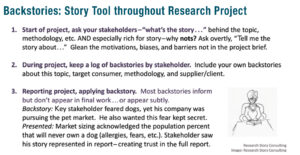

Chapter 4. Use Story Sooner than Later

Researchers often wait until the reporting phase to tell a user-driven story, at which point it may be overwhelming to shape a singular narrative that frames what users say in a way that is useful for organizations to decide what to do next.

“I always hear, ‘I have all this data, how do I make a story out of it?’” says Cox. “I’m passionate that storytelling doesn’t have to come at the end of a project.”

Asking your stakeholders to tell a story of their own can reveal hypotheses, biases, and institutional beliefs that could be at odds with what users say and feel. But building in time at the beginning of a project such as having your stakeholders go through the same exercises as your users—like filling out that March Madness bracket to vote for their winning concepts—can be a valuable way of shaping a story as you move throughout research.

To illustrate this, Cox tells the story of a high-level executive who once proclaimed that they should go in a certain direction because, “green cards don’t sell.”

“I knew there must be a story behind that claim. People don’t get so provoked without there being a story behind it,” Cox reflects. By asking this person to retell the story that shaped this belief, Cox got a better understanding of some of the organization’s preconceived notions that were making their way into product strategy.

With another client, Cox encountered tension between a research supplier wanting to deliver a bigger strategic story, but the end-client being adamant about seeing survey results question by question.

“Two biases are at odds—first, there’s the researcher’s bias that storytelling is limited to presenting one big story from a project, like an Instagram-worthy ice cream sundae with twenty spoons. The second bias, the client’s, is that research findings should be served up in twenty single-scoop surveys or discussion guide answers. Knowing both biases, we reframed the report to be more like a Baskin-Robbins experience. Everyone got their own flavor, or ‘mini-story’ from the survey answers. The researcher linked these mini-stories into themed groupings, therefore satisfying their need to deliver overarching insights, but did not force one overarching story. Maybe not as dramatic as a giant sundae, but who really finishes one of those anyway?”

“We don’t necessarily use these projective stories on ourselves, but they can help you discover your biases,” says Cox. When you begin a research project aware of your own biases, as well as those held by an organization, you can more strategically build a story as you move through research rather than waiting until the reporting phase to have to tie all the ends together.

Epilogue

Throughout her career, Nancy Cox has used storytelling techniques to engage users, inspire stakeholders, and empower professionals of all kinds to think outside the box when it comes to storytelling. With these four lessons in hand, I hope you too feel moved to write your own.

You’re bright as a buttercup, bold as a morning glory… Now don’t you feel excited to go tell a story?

The End.

Be the first to comment