“The Asian century has begun. Asia is the world’s largest regional economy and, as its economies integrate further, it has the potential to fuel and shape the next phase of globalization… By 2040, the region could account for more than 50 percent of global GDP and about 40 percent of global consumption.”

–McKinsey Global Institute, Discussion Paper, September 2019

This bold assessment was made in the pre-COVID-19 world. While the COVID-19 pandemic had an impact upon world economies, prominent voices in the world of finance and macroeconomics still paint the picture of “the Asian century.” In a December 2020 interview with Nikkei Asia, Patrick Winter, the managing partner of Ernst & Young Asia-Pacific said, “What I do see going forward is that this unprecedented opportunity to reimagine the future, and the Asia-Pacific’s ability to manage through COVID’s disruption, will put it in a very strong position over the next twenty years to really develop its footprint as the dominant area of the global economy.”

The Asian economic, social, and cultural shifts are interlinked, but each may occur at a different pace, which can create tension points in consumers’ lives and provide opportunities for brands. For over twenty-five years, I have designed and conducted research across Southern and Southeast Asia, and through that experience, have developed an intimate view of the changes in the region. My research journeys have taken me from observing young people in small towns of India to hanging out with women in the bustling cities of Vietnam or Indonesia to watching women do their laundry in Thailand, Malaysia, and Cambodia.

Prior to COVID-19, conducting research in Southern and Southeast Asia meant exploring unprecedented social change. In the past decades, rapid urbanization has been affecting collective societies and family relationships and has accelerated transformations over the course of just one generation. My Asian experience and the lessons I have learned have global value, particularly now, with COVID-19 having forced the entire world to deal with change at an unprecedented pace.

I’m going to share the stories of three young women from three different Asian cities. Ria, Siti, and Trang are all part of a generation that embodies the transformation I’ve witnessed in the region. It is not a coincidence that they all are women, as women are often at the center of these transitions, and their lives encapsulate the shifts. Their stories provoke us to reflect on how we think about, study, and communicate change.

Ria’s Story: Aligarh, India

About 43 percent of the urban population of India lives in cities with populations of around one million people. It is estimated that urban India will contribute to nearly 70 percent of the GDP by 2030.

Based on this population trend, a mobile phone manufacturer wished to develop a phone that would improve the quality of life of youth in these small but rapidly growing boomtowns. In an immersive approach, we spent time with thirty-two young people across four regions, visiting their homes, hanging out with their friends, and visiting their colleges. One of these people is Ria (name has been changed), a 17-year-old living in Aligarh, a smaller (population under one million) but rapidly growing city in North India, located somewhere between the Ganges and the Yamuna rivers.

Ria welcomed us into her “living room,” a twenty-square-foot space. Against the wall was an iron bed with a well-worn mattress where her frail grandmother laid languidly, and in the corner was an open kitchen where her mother busily prepared tea for our visit.

Ria smiled and spoke to us about starting her own business, perhaps a beauty salon for working women. She had seen many girls on the internet sharing beauty tips and developing fan followings. She told us of her plan to take up a job in the city to learn the right skills and save some money first. Her mother, a housewife, smiled tentatively when she heard this.

Getting a job will be difficult, Ria admitted. “I need to ace a job interview. I will be the first woman in my family to study and think about starting a business.” When asked how she planned to do this, she grabbed her phone and said, “I read articles about how to dress up for an interview or how to respond to questions during the interview. There is a lot of information available.” Ria’s mother chimed in, “Things are very different now. There are a lot of opportunities and new ways of doing things. I don’t understand it.”

During our research, I met many other young women like Ria who live in small towns but have big dreams. The rapid cultural and economic changes have left their parents ill-equipped to guide them through the new world, and an entire generation of youth is trying to figure out their way through the change by themselves. In many ways, they can be considered the “lost generation.”

In the 2018 book, Dreamers: How Young Indians Are Changing the World, author Snigdha Poonam asks, “What happens when one hundred million people suddenly start dreaming big, in a place where no one is prepared for it—families, teachers, employers, governments? They realize they are on their own. They reconcile themselves to the idea that they must build a world in which they can be what they want to be, and where how well you do depends on how badly you want to do well. Once they have created this bubble of aspiration, they chase their dreams like their life depends on it—do or die.”

This insight of the “lost generation” became the inspiration for how a new mobile phone proposition could be crafted, the features that can be developed to improve the lives of youth in small towns.

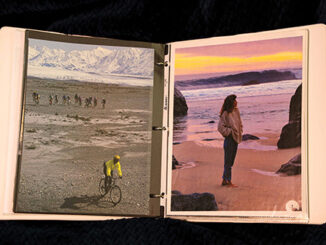

Youth in smaller cities in India rely on newspaper clippings (here, tucked into a handbag) to learn about preparing for job interviews.

Siti’s Story: Jakarta, Indonesia

The urban consuming class of fifty-five million in Indonesia is growing by more than five million people each year, which is equivalent to the entire population of Singapore, another Southeast Asian country with a growing economy.

Indonesia is a market where local brands thrive and compete successfully with global brands. A global cosmetics brand wished to gain a deeper understanding of a target group of young women in order to successfully compete for the hearts and minds of this vibrant market. Siti (name has been changed) is part of this emerging urban consuming class. We interviewed her and other women like her in their homes and also hung out with them and their friends as they did activities outside the home.

As part of my interaction with Siti, I went shopping with her and her friends at their favorite mall. What was most striking about Siti was her sparkling eyes; her youthful face was bright, and she was well groomed. As a teenager, her life was full of social activities from hanging out with friends to enjoying time with immediate and extended family.

Siti and her friends walked around the shops and stopped at the makeup bar in the mall’s department store. Like kids in a candy store, they excitedly tried out different shades of lipstick. After much laughter and teasing about boys—with no purchases made—it was time to rest at one of the cool cafés frequented by the city’s young people.

“I am looking forward to going to college; it is a different phase of life. In school I did not care much about how I looked, but in college you have to be more careful, otherwise no one will want to be friends with you,” Siti said. She then added, “My aunt sent me makeup from overseas for when I started going to college. She says eyes are the windows to your soul and that, as girls, it is important to look feminine.”

In households across Indonesia, young girls are groomed by their mothers to prepare them for their most important role in life as wives and mothers; but now, female aspirations toward professional careers are getting stronger. This requires a shifting view on femininity and the role of women at home and in society.

This insight on what femininity means to the target group provided the spark for a first of its kind marketing campaign proposing more relevant grooming journeys to women.

In Indonesia, as more young women aspire to professional careers, beauty skills are sometimes seen as a way to achieve entrepreneurial ambitions.

In Indonesia, as more young women aspire to professional careers, beauty skills are sometimes seen as a way to achieve entrepreneurial ambitions.

Trang’s Story: Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

Vietnamese women are entrepreneurial, with a 73 percent female labor force participation rate (The World Bank Data, 2019). Traditionally, women have predominantly been employed in the informal sector selling wares from shops. Now, new job opportunities that require more focused skills are emerging, bringing better jobs and higher incomes. We conducted a study for one of our clients to understand the aspirations of young women and uncover ways for communicating with them.

I met Trang (name has been changed) and her friend Linh at their hangout in District 1, which is in the commercial hub of Ho Chi Minh City. Through the glass doors was the air-conditioned Koi café, a Taiwanese chain of premium bubble tea that is all the rage among young people in the city. By 9:30 a.m., its modern interior was already buzzing with groups of friends enjoying a conversation or quietly surfing on their smartphones.

Trang proudly talked about being a part of the modern world and having an “international” lifestyle typified by connectivity, convenience, consumption, and exploration. Trang and Linh are part of the post-war generation. They have grown up in peaceful times characterized by economic growth, rising income, and a relatively comfortable life.

Economic growth and more work opportunities have led to a shift in aspiration among these young girls. Rather than owning a small business like a street food stall or a steady government job, they want to work in dynamic foreign companies and be “office ladies.” The young generation is brimming with optimism and hope about Vietnam’s future. Girls like Trang are conscious of the role they play in propelling the country forward and want to make sure they do not get left behind by neighboring countries like Thailand.

Being among the early participants of the transforming economy has its challenges. The Confucian ideals of self-cultivation are the key routes to vertical mobility in the country, and young girls strive to prepare themselves with the different skills that are relevant today. In school, they attend classes on how to communicate, present, and persuade. Out of school, they join additional English language and computer classes and continue to strive in their own way.

Armed with a deep understanding of the mindsets of Vietnamese women, the brand developed marketing plans to connect with women’s aspirations and make the brand more meaningful.

The young generation in Vietnam is brimming with optimism; economic growth has led many young women to aspire to work in dynamic international companies.

Conducting Research in Times of Transformation

“True life is lived when tiny changes occur.” —Leo Tolstoy

Conducting research in a region undergoing cultural and economic transformations provides a fascinating front-row view of how this change unfolds. In post-COVID-19 times, understanding change will help us anticipate what is to come so we can think about possibilities and be generative about creative solutions. I will share some suggestions:

- Focusing on the small change (zooming in) will help us understand the bigger change (zooming out). Biographical stories can provide a window into the process of social and cultural change. Ria, Siti, and Trang’s stories are about aspirations that shape Asia and the opportunities for harnessing these effectively.

- Looking at change as a continuum rather than as a dichotomy provides a better appreciation for that change. Dichotomies present contrasting truths that are particularly difficult to make sense of a complex world. In Asia, it would be easy to think of traditional versus modern as a dichotomy; however, the truth lies in a range of possibilities in-between. All three women are stretching the boundaries by advancing toward their individual goals without abandoning collective values.

Exploration of rapidly changing cultures uncovers stories that inspire brands to innovate and communicate in increasingly relevant and even provocative ways. Change can be scary, but it is a force that is hard to stop. As researchers, the stories we tell become the springboard for opportunities in our ever-changing world. So let’s embrace the change and help put great ideas into the world.

Be the first to comment