One day I was driving home from picking up my three-year-old daughter from preschool and she asked me, “What’s that big wheel that you always turn?” After giving her my best explanation of steering wheels (and realizing I had no idea how to even passably answer her question), I flippantly said, “But you probably won’t ever even need a steering wheel.” That got her attention and we launched into an exchange about the onset of driverless cars that dovetailed into me filling her mind with the vision of a Jetsons-like future. Satisfied I had given her plenty to think about, I started pulling up a song to play.

“But how will the robots know that I want my car to be black and yellow, like a bumblebee?”

Many people have predicted a future of Big Data, data science, machine learning, AI, IoT, neural networks, etc., that put traditional primary market research right out of business. The general contention seems to be “Why would we bother asking people what they think or what they intend to do when we can analyze everything they’ve ever done and make a much more accurate assessment?” It is a question worth pondering. As researchers, we spend so much time controlling for sample frames and innumerable biases and dishonest respondents, etc., etc., etc. Is it possible that there is a freight train coming carrying the tools to render our methods irrelevant and do our jobs without ever so much as sending a single email or making a single phone call?

If there is a war coming on the beachhead of market research between quantitative methods and Big Data, qualitative approaches and practices will be in a lounge chair, sipping a piña colada, watching indifferently as it is waged. The robots won’t know my daughter wants a bumblebee for a car. They will need a person to ask her.

There is no endeavor to understand and predict market conditions, consumer behavior, employee engagement, advertising effectiveness and any of the other building blocks of business success that will ever fully realize its objectives without qualitative research. The big data revolution is no exception to that reality and, in fact, amplifies its necessity. Here are a few of the key reasons why.

The Cart Before the Horse

The Cart Before the Horse

“Your scientists were so preoccupied with whether or not they could that they didn’t stop to think if they should.”

– Dr. Ian Malcolm, Jurassic Park

While data scientists have raced to create machine learning algorithms and neural networks that track our every action and use the data to fundamentally alter our consumer experience, they seem to have overlooked one particularly important question—how will people actually react to these? If you are like me and the people with whom I interact, you’ve moved past being astounded by the speed and targeting of online advertising driven by data mining and algorithms. In fact, you now find yourself irritated and probably more than a little unnerved. A poll from Pew Research of 4,135 American adults showed that 72% are either very or somewhat worried about “a future where robots can do many human jobs,” compared to just 33% who are either very or somewhat enthusiastic.

To be clear, I’m no technophobe and I am also a realist. If there is a competitive edge to be gained in business by having math and machines do the heavy lifting, we would be foolish to think corporations aren’t going to use them. The differentiator between those who do so successfully and those who alienate, or even frighten, the market will be the extent to which they let human beings determine exactly where, when, how, and for what.

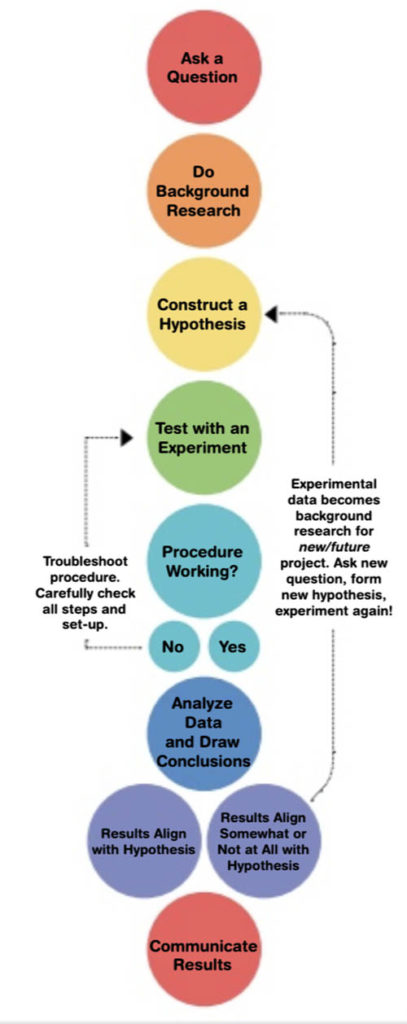

In addition to yielding fully realized insights, qualitative research methods (such as focus groups, IDIs, ethnographies, shop-alongs, and usability testing) are the incubators of data-driven decision making. Consider the scientific method itself. As we examine its steps—ask a question, do background research, construct a hypothesis—one can readily see how researchers strive to conduct qualitative research and/or mixed-mode market research according to its tenets.

Can the same be said for many of the products and services that Big Data has delivered to us? If so, it is difficult to see how.

As an exercise, ask yourself a question: when did an algorithm first make a decision that you had previously made for yourself? Did you have any advance notice or opportunity to express your opinion? Or, did you one day realize that Facebook was only showing you the activity of a fraction of your friends, or that Netflix was feeding you the type of content preferred by someone else in your household? How did you feel? Amazed? Deceived? Frustrated?

Several years ago, I fell in love with Spotify, the popular music streaming service. I couldn’t believe how it generously handed me any song or album whenever I asked. It had it all. I could build playlists, share them with friends, text songs to other subscribers, and interact with more music in more ways than I ever thought possible. After a brief courtship, I pushed all the downloaded music I had onto an external drive, shoved it in a drawer, and Spotify and I began our life together.

Then it began to act strange. It was clear when we first got together that I could be moody. I liked to build large playlists and play them on shuffle, but I was also a habitual song-skipper. On playlists of 1,000+ songs, I began to hear the same 40 or 50 songs too often to be considered random. As I investigated further, I noticed that it was almost never playing a song that I had previously skipped and if I listened to something twice, it would then come on frequently. The problem grew to where I had to abandon my preferred way of engaging with music. Spotify’s algorithm was fretfully trying to give me what I wanted, when all I wanted was for it to go away.

Of course, after moving twice since our relationship began, that hard drive I put in the drawer is off on the wind. Music itself, one of the great joys of the entire human experience, is now compromised. When I do turn on Spotify, it can tell that I’ve been listening to podcasts.

One wonders, what if my experience with Spotify had been as a participant in an ethnographic study? What if I had been able to hand the whole thing back and say, “no, there is no way to perfect your algorithm for someone like me other than to not have it.”

Stumbling upon Disaster

“I know that I know nothing.”

– Socrates

The scope and magnitude of change that some of these technological advancements portend is so profound, not only is qualitative research going to be a huge component of paving their way, in many cases it will be the only way. As technology continues to develop, it solves many consumer, employee, and market roblems while simultaneously causing new ones. As we plow forward into this brave new world, we can’t even know what it is we don’t know.

Let’s revisit the driverless car for a moment. Stop to consider the reverberations throughout society and industry if no one drives anymore. The best projections say that by 2020, they will start to register on the market, and by 2040 ninety-five percent (95%) of the cars on the road will not be driven by human beings.

Let’s look at the role our three data collection methods can play here: big data and analytics, quantitative, and qualitative research.

Let’s look at the role our three data collection methods can play here: big data and analytics, quantitative, and qualitative research.

Big Data, IoT, AI, robotics, machine-learning, etc., are helping make this a reality. The people employing these tools see a set of objectives, opportunities, gaps in efficiency—and they are using them to build solutions. As we have established, the petabytes of data being analyzed in this pursuit consider macro-level market trends without regard for the diversity of localized consumer motivations, wants, and needs.

What about a survey? Sure, we can do a survey of people who may or may not want a driverless car and see what they think. The methodological playbook would suggest questions about current perceptions, future intent, preferences, perhaps brand and advertising metrics. It would give us answers… but would they be answers to even the right questions? Would they give us even a fraction of the full range of insights we are seeking, and if so, how would we know?

Now, consider a focus group where a trained professional gathers all relevant aspects of the research objectives and brings them into a deep and organic data-collection process. When most people think about the benefits of driverless cars, increased safety is at or near the top of the list. If 95% of the vehicles on the road ostensibly can’t get in accidents in just 20 years, here is a quick, top-of-mind list of industries that will be decimated, crippled, or irrevocably altered.

- Automotive sales

- Automotive repair

- Insurance

- Health care

- Law enforcement

- Taxis / Transportation

- Licensing

- Legal

- Home Delivery

- End of Life Services

No decent person would ever argue against a product or service that would all but eradicate the third leading cause of death in America, let alone countless injuries and suffering, but above is a list that could portend economic collapse if this isn’t done right. If nothing else, who will buy driverless cars if they’ve put everyone out of work?

These are the types of unprecedented market changes that are coming and, thus far, the data solutions that create them haven’t done a great job of asking consumers what they think about everything they will mean. That is a categorical imperative and a step that simply cannot be done properly without qualitative approaches.

Hard Reset

“Anything your heart desires will come to you…”

– Jiminy Cricket, Pinocchio

Qualitative research methods remove one critical, but all-too-common, aspect of the decision-making process for those who bring products and services to market—presumption. They stop the disconnected from making decisions about how people will interact with the world based on misguided intuition, guesswork, or simply because they can. What can be done seems to be the driving force behind the Big Data revolution, rather than what should.

As far back as history has recorded, societal need and consumer demand have been the driving force behind production. Human beings have developed an existing need and the market has grown by rewarding those who fill it. For example, railroads and automobiles were a practical response to people’s need to travel longer distances faster than they could with horses. Now, for the first time it would seem, innovation is outpacing or ignoring those consumer demands. Indeed, this reversal of process has led to some of the great innovations and life-enriching products of our time. How many of us knew we needed an iPod or a robotic vacuum cleaner before we got one? However, there are many cases in which considerable, often unintended consequences have arisen from barreling forward without a full understanding of consumer experience and impact.

Most of us know a teenager and we can see how much more complicated and treacherous their lives are with how social media and technology can be exploited. For example, we live in a society where domestic abusers can use mobile spyware to follow an unsuspecting partner. On top of geo-location services, one need only gain momentary access to another’s cell phone to listen to calls, record them, read texts, see photos, and even watch a person via the camera in their phone.

Surely, those who created these software tools didn’t want to see this kind of outcome, but here we are. What now?

The express path to consumer safety, engagement, loyalty, and business success is to let people back into every step of the conception, development, testing, and use of the products and services. Yes, it adds time or expense to bringing services to market. But otherwise, we are at the mercy of solutions like algorithms, AI, IoT, machine learning, neural networks, and Big Data analytics which seem to drop into our lives with a “shoot first, ask questions later” approach.

While quantitative research methods will play a key part in getting consumer feedback, the journey to market begins with qualitative and relies on it throughout the life cycle of a product or service experience. If the only limits on the future of product design and customer experience are the human imagination, the process of gathering the opinions and perceptions of those consumers must be similarly boundless, and thus built on a foundation much more befitting qualitative methods than even traditional surveying. That is not to say that quantitative primary research isn’t a critical outpost along this newly emerging path of customer engagement, just that it is not where it begins.

“Wait!” says the data scientist, or developer, or any one of the dozens of people in the line of production. “We can’t possibly take the time to conduct all of this research with our potential customers. Company X is cleaning up in the marketplace and companies Y and Z are hot on my tail. If I don’t get this out fast, we’re dead in the water.” Are you? If you overlook real market needs in order to be fast or first, might you not end up in a worse position?

Who among us remembers “The Zune,” Microsoft’s loaded-with-new-features response to Apple’s iPod?

If being fast to market were paramount in engaging customers, we’d all be reading this via our AOL connections, asking Jeeves any questions it might raise, and posting our thoughts on our MySpace pages.

It is time for a hard reset, and for the chasm between big and small data to be bridged. If the world is our oyster as far as what we can have, shouldn’t we first ask everyone how they feel about oysters? We need to throw out much of what we think we already know and start over at a very basic level. Imagine a partnership where the greatest tech minds are in partnership with the greatest minds in market research.

We can start with a focus group that has this first sentence on the moderator guide: “How can we help?”

1 Trackback / Pingback